PREVALENCE OF PHYSICAL INACTIVITY AMONG ADOLESCENTS IN BRAZIL: SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF OBSERVATIONAL STUDIES

PREVALENCIA DE INACTIVIDAD FÍSICA EN ADOLESCENTES DE BRASIL: UNA

REVISIÓN SISTEMÁTICA DE ESTUDIOS OBSERVACIONALES

PREVALÊNCIA DE INATIVIDADE FÍSICA EM ADOLESCENTES DO BRASIL: UMA REVISÃO SISTEMÁTICA DE ESTUDOS OBSERVACIONAIS

Beatriz Angélica Valdivia Arancibia

Maestranda por la Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina (Brasil).

Investigadora de la Línea de investigación Actividad Física y Salud, Centro de Ciencias de la Salud y del Deporte (CEDIF) y Laboratorio de Actividad Motora Adaptada (LABAMA).

Profesora Licenciatura en Educación física en la Universidad Católica Silva Henríquez (Santiago de Chile - Chile).

[email protected]

Franciele Cascaes da Silva

Doctoranda por la Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina (Brasil), Fisioterapeuta por la Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina (Brasil).

Investigadora de Línea de investigación Actividad Física y Salud, Centro de Ciencias de la Salud y del Deporte (CEDIF) y Laboratorio de Actividad Motora Adaptada (LABAMA) (Santa Catarina - Brasil).

[email protected]

Patrícia Domingos dos Santos

Maestranda y Fisioterapeuta por la Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina (Brasil), Licenciada en Educación por la Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (Brasil).

Investigadora de Línea de investigación Actividad Física y Salud, Centro de Ciencias de la Salud y del Deporte (CEDIF) y Laboratorio de Actividad Motora Adaptada (LABAMA) (Santa Catarina - Brasil).

[email protected]

Paulo José Barbosa Gutierres Filho

Doctor en Ciencias del Deporte por la Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro (Portugal).

Investigador y Profesor del Programa de Pos Graduación en Educación Física de la Universidade de Brasília, Línea de investigación Actividad Física y Salud, Actividad Física Adaptada (Brasilia – Brasil).

[email protected]

Rudney da Silva

Doctor por la Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina (Brasil).

Profesor Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina (Brasil) e Investigador de la Línea de investigación Actividad Física y Salud, Laboratorio de Actividad Motora Adaptada (LABAMA), (Santa Catarina – Brasil).

[email protected]

Arancibia, B. A. V., Silva F. C., Santos, P. D., Filho, P. J., Silva, R (2015). Prevalence of physical inactivity among adolescents in Brazil: systematic review of observational studies. Educación Física y Deporte, 34 (2), Jul.-Dic.. http://doi.org/10.17533/udea.efyd.v34n2a03

DOI: 10.17533/udea.efyd.v34n2a03

URL DOI: http://doi.org/10.17533/udea.efyd.v34n2a03

ABSTRACT

Aims: To analyze the available evidence on the prevalence of physical inactivity among Brazilian adolescents by means of a systematic review of observational studies. Method: They were used 3 databases and 3 virtual libraries with key descriptors of this subject. After applying the eligibility criteria 22 item were identified. Results: the studies showed that over 50% of adolescents are inactive, identifying a higher prevalence in female adolescents. Furthermore, several factors may interfere in this practice (age, sex, socioeconomic status and sedentary behavior). Conclusion: The physical activity acts as a protective agent for health, becoming important at the adolescence, thus promote public and private policies will serve to enhance the physical activity in this population encouraging healthy habits into adulthood.

KEY WORDS: Sedentary Lifestyle, Physical Inactivity, Adolescents, Brazil, Observational Studies.

RESUMEN

Objetivo: analizar la evidencia disponible sobre la prevalencia de la inactividad física en adolescentes brasileños, a través de una revisión sistemática de estudios observacionales. Método: se usaron 3 bases de datos y 3 bibliotecas virtuales con los descriptores principales de este tema. Después de aplicar los criterios de elegibilidad se identificaron 22 artículos. Resultados: los estudios mostraron que más del 50% de los adolescentes son inactivos, identificando una mayor prevalencia en adolescentes de sexo femenino. Por otro lado, varios factores pueden interferir en esta práctica (edad, sexo, nivel socioeconómico y el comportamiento sedentario). Conclusión: la actividad física actúa como un agente protector para la salud, y se torna fundamental en la etapa de la adolescencia, por lo tanto la promoción de políticas públicas y privadas servirán para potenciar la práctica de la actividad física en esta población, fomentando hábitos saludables en la edad adulta.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Estilo de Vida Sedentario, Inactividad Física, Adolescentes, Brasil, Estudios Observacionales.

RESUMO

Objetivo: analisar a evidencia disponível sobre a prevalência de inatividade física em adolescentes brasileiros por meio de uma revisão sistemática de estudos observacionais. Método: foram utilizadas três bases de dados e tres bibliotecas virtuais sendo utilizados os descritores principais desta temática. Após a aplicação dos critérios de elegibilidade foram identificados 22 estudos. Resultados: os estudos demonstraram que mais do 50% dos adolescentes são inativos, identificando uma maior prevalência no sexo feminino. Por outro lado, existem diversos fatores que podem interferir nesta condição (idade, nível socioeconómico, e comportamento sedentário). Conclusão: a atividade física atua como agente protetor para a saúde, tornando-se fundamental na fase da adolescência, promovendo assim, políticas públicas e privadas que serviram para potencializar a prática de atividade física nesta população fomentando hábitos saudáveis na vida adulta.

PALAVRAS CHAVES: Estilo de Vida Sedentário, Inatividade física, Adolescentes, Brasil, Estudos Observacionais.

INTRODUCTION

Physical activity is one of the main components of healthy lifestyles for people of any age. Considering adolescence in particular, some evidence indicates that physical activity promotes physical (musculoskeletal, cardiorespiratory, and metabolic, among others) and mental (mood, anxiety and stress, among others) health benefits (CDC, 2011). According to Strong et al. (2005), in the case of adolescents, regular physical activity must include 300 minutes of moderate and vigorous activities per week however, several studies show that adolescents fail to meet that goal (Guedes et al., 2001; Hallal et al., 2012; Pelegrini & Petroski, 2009; Silva et al., 2005; Zoeller, 2009).

Studies conducted in Brazil have reported high rates of physical inactivity (Farias, 2006; Farias et al., 2011; Fernandes et al., 2011; Gomes et al., 2001; Silva & Malina, 2000), and such high rates of physical inactivity have been associated with risk factors and health disorders that potentiate the occurrence of chronic diseases, including obesity and hypertension (Ceschini et al., 2007; Farias, 2006). Variations in the prevalence of physical inactivity among Brazilian adolescents have been reported by several authors (Hallal et al., 2007; Pinto et al., 2011; Seabra, et al. 2008), who have suggested a wide scope of causes to account for that fact, including cultural, geopolitical and economic issues, among others.

In this sense, there is a need to review the updated scientific production (2010-2014) identifying the increase, decrease or maintenance of physical inactivity over the years, in order to verify if the mechanisms and strategies are being effective for combating physical inactivity in Brazilian adolescents.

Thus, the aim of the present study was to analyze the available evidence on the prevalence of physical inactivity among Brazilian adolescents by means of a systematic review of observational studies.

METHOD

This systematic review was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews – PROSPERO (CRD42014013092) and followed the recommendations suggested by the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins & Green, 2011) and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement (Moher et al., 2009).

Eligibility criteria

For this review, cohort, cross-sectional and case-control observational studies that addressed physical inactivity and sedentary among Brazilian adolescents, without language restriction, with available abstracts and online access to their full text, and published from 2010 onwards were selected. The reason for the time limit was that a meta-analysis on the prevalence of physical inactivity among Brazilian adolescents included articles published until 2010 (Barufaldi et al., 2012).

Search strategy

The search was conducted in August and September 2014 on the electronic database Medline (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System on-line) via PubMed, Web of Science andScopus (Elsevier) and in the virtual libraries Adolec, Lilacs (Literatura Latino-Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde - Literature in the Health Sciences in Latin America and the Caribbean) and SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online). Those databases were selected because they index studies on health sciences. The search strategy included keywords listed in Medical Subject Headings (MesSH) related to sedentarism - "Sedentary Lifestyle", “Lifestyle, Sedentary”, “Lifestyles, Sedentary”, “Sedentary Lifestyles”, “Physical Inactivity”, “Level of Physical Activity”; adolescents - "Adolescent", “Adolescents” OR “Adolescents, Female” OR “Adolescent, Female” OR “Female Adolescent” OR “Female Adolescents” OR “Teens” OR “Teen” OR “Teenagers” OR “Teenager” OR “Youth” OR “Youths” OR “Adolescence” OR “Adolescents, Male” OR “Adolescent, Male” OR “Male Adolescent” OR “Male Adolescents”; Brazil - "Brazil" OR “Brazilian”; and type of study - "Longitudinal", "Cohort", "Case Control", and “Epidemiologic studies”.

Identification of studies

Two reviewers independently performed the search. First, they assessed titles and abstracts, and the full texts of the articles thus identified were evaluated based on the aforementioned eligibility criteria. The discrepancy can be resolved by consensus between the pair, or consulting a third reviewer.

Assessment of study quality

The two reviewers also independently assessed the methodological quality of all the studies included in this review using an instrument elaborated by these authors Silva et al. (2013), based on both the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) (Wells et al., 2000), which has been used to assess the quality of randomized and non-randomized studies, and the questionnaire elaborated by Sarmento et al. (2013) to evaluate the quality of observational studies.

RESULTS

Literature survey

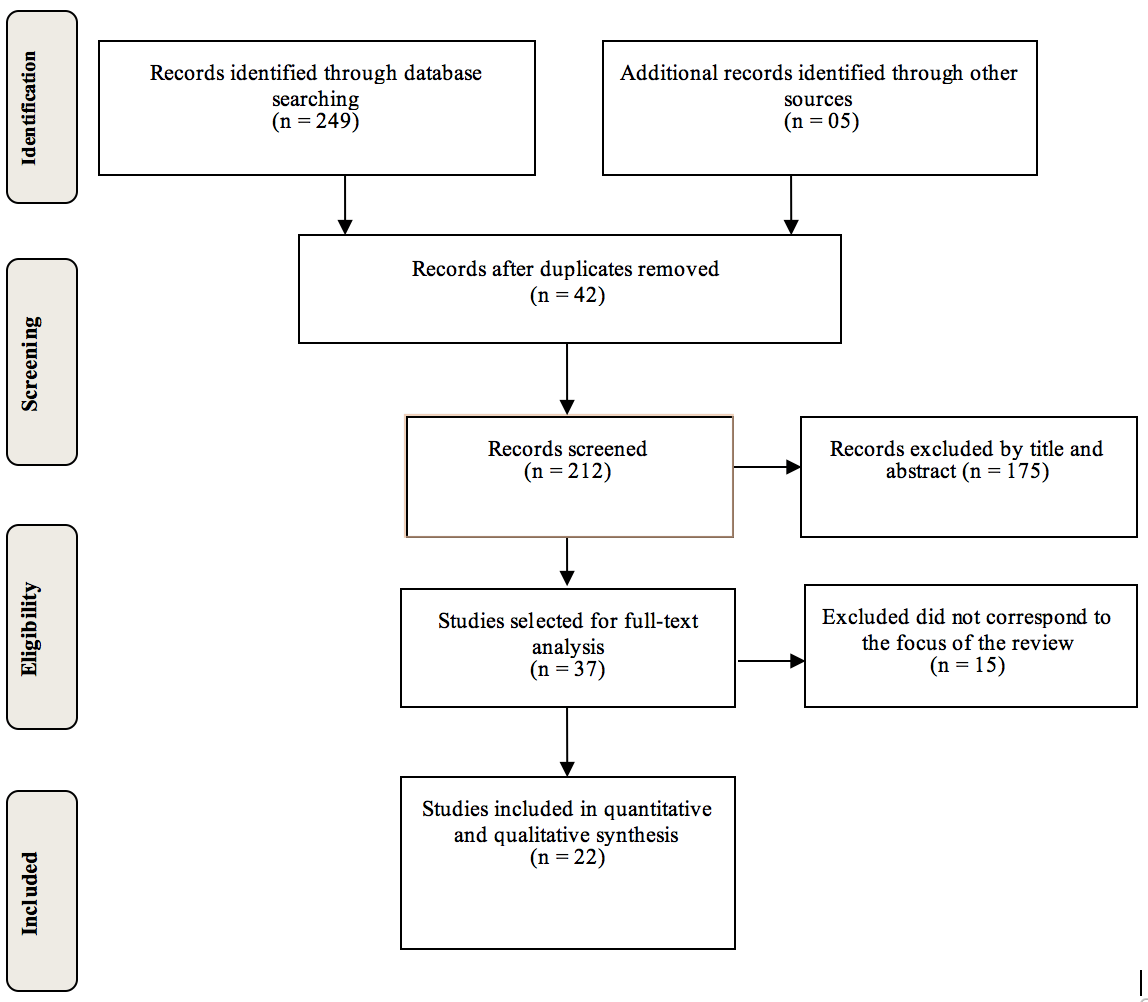

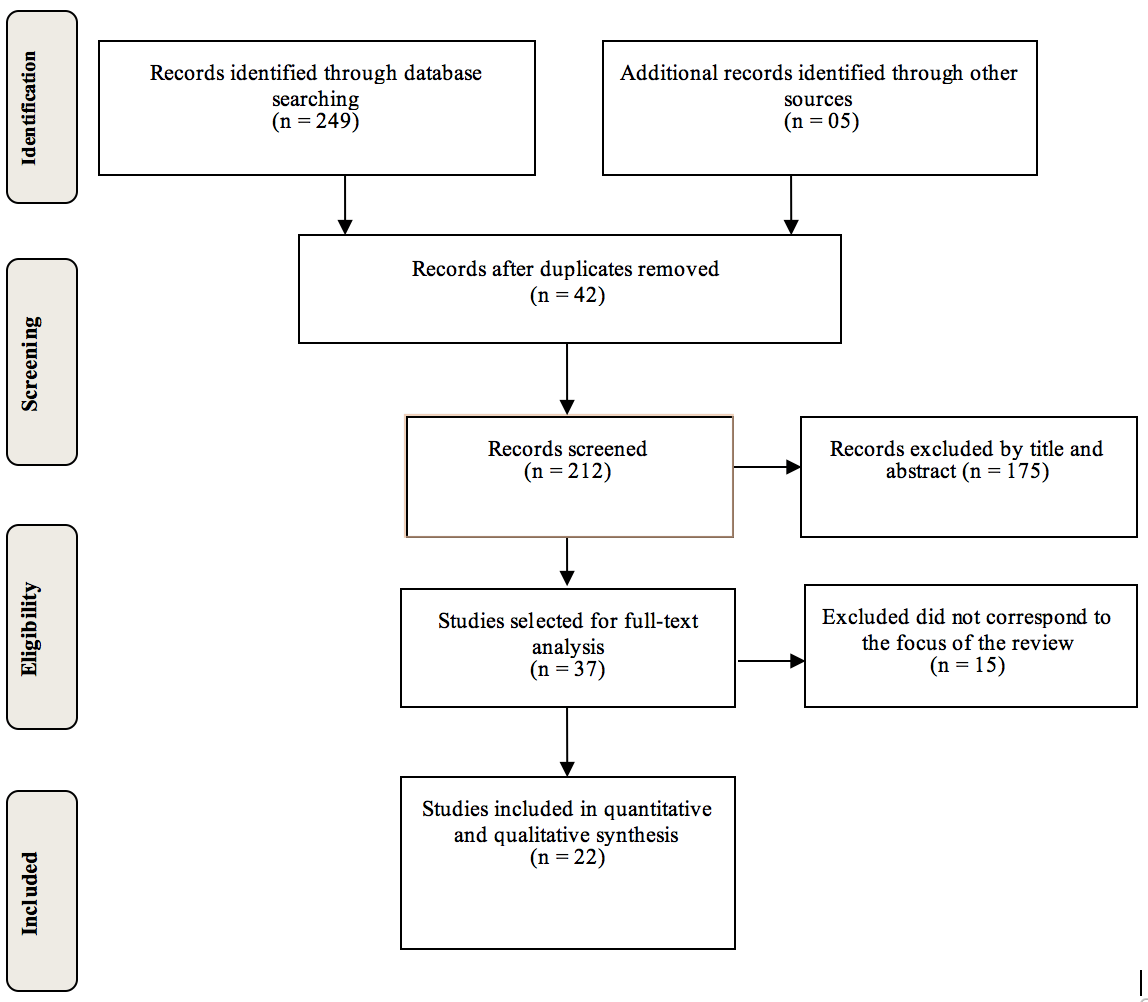

The initial survey located 249 studies, from which 232 were excluded for being duplicates, based on their titles and based on the abstract, thus, only 17 studies were included. Manual search of references cited in those articles was performed, which allowed five further articles to be located. Therefore, 22 articles were included in this review. The process for study selection is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart representing the articles included in this systematic review

Study characteristics

The main sociodemographic and methodological characteristics of the included studies are described in Table 1. In a detailed analysis, a higher proportion of identified studies were conducted in the northern and southern Brazil. The most of the studies are cross-sectional designs.

Author, year |

Location |

Gender |

Age range |

Design |

Sample |

Assessment method |

Cutoff point for physical inactivity |

|

1. Silva et al. (2010) |

Sergipe |

Mal./Fem. |

17 |

Cross-sectional |

281 |

Questionnaire, Marcus |

- |

|

2. Souza et al. (2010) |

Bahia |

Mal./Fem. |

10 to 14 |

|

694 |

QAFA, Florindo et al. |

-< 300 min/week MVPA |

|

3. Lippo et al. (2010) |

Pernambuco |

Mal./Fem. |

15 to 19 |

Case-control |

597 |

IPAQ |

- |

|

4. Fermino et al. (2010) |

Paraná |

Mal./Fem. |

14 to 18 |

Cross-sectional |

1518 |

Q - GSHS |

< 300 min/week / MVPA |

|

5. Rivera et al. (2010) |

Alagoas |

Mal./Fem. |

10 to 17 |

Cross-sectional |

1253 |

PAQ-C |

Score < 2 |

|

6. Freitas et al. (2010) |

Ceará |

Mal./Fem. |

12 to 17 |

Cross-sectional |

307 |

Form, Interview |

< 30 min / day / MVPA |

|

7. Vasconcelos et al. (2010) |

Ceará

|

Mal./Fem. |

12 to 17 |

Cross-sectional |

794 |

Structured interview |

< 30 min / day AFMV |

|

8. Romero et al. (2010) |

São Paulo |

Mal./Fem. |

10 to 15 |

Cross-sectional |

328 |

QAFA, Florindo et al. |

< 300 min/week/ MVPA |

|

9. Tenório et al. (2010) |

Pernambuco |

Mal./Fem. |

14 to 19 |

Cross-sectional |

4210 |

Q - GSHS |

< 300 min/week/ MVPA |

|

10. Campos et al. (2010) |

Paraná |

Mal./Fem. |

10 to 18 |

Cross-sectional |

497 |

Bouchard’s Activity Diary |

< 300 kcal/kg/ day |

|

11. Santos et al. (2010) |

Paraná |

Mal./Fem. |

14 to 18 |

Cross-sectional |

1609 |

CDC |

< 300 min/week/ MVPA |

|

12. Silveira & Silva (2011) |

Rio Grande do Sul |

Mal./Fem. |

13 to 19 |

Cross-sectional |

1233 |

Domingues et al. questionnaire |

- |

|

13. Beck et al. (2011) |

Rio Grande do Sul |

Mal./Fem. |

14 to 19 |

Cross-sectional |

660 |

Ad hoc questionnaire |

< 300 min/week/ MVPA |

|

14. Dumith et al. (2012) |

Rio Grande do Sul |

Mal./Fem. |

11 to 15 |

Cohort |

4120 |

Ad hoc questionnaire |

- |

|

15. Alves et al. (2012) |

Bahia |

Mal./Fem. |

10 to 14 |

Cross-sectional |

803 |

QAFA, Florindo et al. |

< 300 min/week / MVPA |

|

16. Guedes et al. (2012) |

Paraíba |

Mal./Fem. |

15 to 18 |

Cross-sectional |

1268 |

IPAQ short version |

MVPA |

|

17. Barbosa et al. (2012) |

Paraná |

Mal./Fem. |

11 to 17,9 |

Cross-sectional |

1628 |

Bouchard’s Questionnaire |

< 420 min/week |

|

18. Coelho et al. (2012) |

Minas Gerais |

Mal./Fem. |

10 to 14 |

Cross-sectional |

414 |

Semi-structured questionnaire |

< 300 min/week / PA |

|

19. Silva Junior et al. (2012)

|

Acre

|

Mal./Fem.

|

14 to 18

|

Cross-sectional

|

741

|

IPAQ versión curta IPAQ short form adolescents |

Mild with little physical effort |

|

20. Bergmann et al. (2013) |

Rio Grande do Sul |

Mal./Fem. |

10 to 17 |

Cross-sectional |

1455 |

PAQ-C/ PAQ- A

|

Score < 2 |

|

21. Moraes & Falção (2013) |

Paraná |

Mal. /Fem. |

14 to 18

|

Cross-sectional |

991 |

Arvidsson |

< 300 min/week / MVPA |

|

22. Leites et al. (2013) |

Rio Grande do Sul |

Mal. /Fem. |

10 to 19 |

Cross-sectional |

967 |

Bastos et al.’s questionnaire |

< 300 min/week / MVPA |

|

Legend: Mal., Masculine; Fem., Female; PA, physical activity; MVPA, moderate- to-vigorous-intensity physical activity; PAQ-C/ PAQ-A, Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Children and Adolescent; QAFA, Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents; Q-GSHS, Global School-bases Student Health Survey; CDC, Center of Disease Control; IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire.

Table 1. Main sociodemographic and methodological characteristics of the studies included for systematic review

From the evaluation methods of physical activity, the results show a variety of instruments and cutoffs that determine physical inactivity (<300 min/week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, or <30 min/day and individuals with energy expenditures less than 37 kcal/kg/day were defined as sedentary.

The main results of the studies included in this review are described in Table 2. The prevalence of physical inactivity among Brazilian adolescents varied from 35.2% (Lippo et al., 2010) to 93.5% (Rivera et al., 2010). It is worth noting that some factors influenced physical inactivity in adolescents, such as gender, age range, screen time, study site and socioeconomic level. As concerns the factors associated with physical inactivity, its prevalence was higher among females (16 studies) compared to males; in addition, the time of sedentary behavior in everyday life was longer among females. Considering the factor age, among adolescents 14 to 15 years old (mid-adolescence) were more active compared to those aged 16 to 19 years old (late adolescents) (WHO, 2002; Guedes et al., 2012; Leites et al., 2013).

Author–Year |

Results |

1. Silva et al. (2010) |

The prevalence of inactivity was 64.8%. Girls were more inactive than boys (74.1% vs. 52.3%, respectively). Low socioeconomic level was a risk factor. |

2. Souza et al. (2010)

|

The percentage of physical inactivity was higher among girls compared to boys (50% vs. 28%, respectively). The participants with lower caloric intake levels exhibited high levels of physical inactivity. |

3. Lippo et al. (2010) |

Physical inactivity was detected in 35.2%; the prevalence among girls was 63.3%. |

4. Fermino et al. (2010) |

Physical inactivity was detected in 41.8%; the proportion of girls with physical inactivity was greater compared to the boys (53.5% vs. 24.9%). |

5. Rivera et al. (2010) |

The prevalence of sedentary behavior was 93.5% (more frequent among females). The mean and median TV times were 3.6 and 3 hours, respectively. |

6. Freitas et al. (2010) |

The prevalence of physical inactivity was 67.4%; girls were more inactive than the boys. |

7. Vasconcelos et al. (2010) |

The prevalence of sedentary individuals was 65.1%. |

8. Romero et al. (2010) |

In the total sample, the prevalence of insufficiently active participants was 54.9%; among girls, the prevalence was 65%. |

9.Tenório et al., (2010) |

The prevalence of insufficient physical activity was 65.1% (70.2% girls; 57.6% boys). |

10. Campos et al. (2010) |

In the sample, 17.3% of the boys and 22.6% of the girls were classified as sedentary. |

11. Santos et al. (2010) |

The inactivity prevalence rates were 77.9% among boys and 90.94% among girls. |

12. Silveira & Silva (2011)

|

The total prevalence of insufficiently active participants was 63.9%. The girls were more inactive than boys (75.7% vs. 50.2%, respectively). |

13. Beck et al. (2011) |

The prevalence of sedentary behavior was 61.2%. |

14. Dumith et al. (2012)

|

At the onset of the study, 62.7% of the participants were inactive (52.3% of boys vs. 72.8% of girls); 68% of adolescents remained inactive throughout follow-up. High socioeconomic level was favorable for greater inactivity. |

15. Alves et al. (2012)

|

The prevalence of physical inactivity was 49.6% (59.9% girls vs. 39% boys). The participants with low socioeconomic levels were more active compared to those with high socioeconomic levels; 48.7% of the participants exhibited sedentary habits (TV time ≥3.3 hours). |

16. Guedes et al. (2012)

|

The prevalence rates of sedentary behavior were 28.2% among girls and 19.1% among boys. Associated factors were parental education, socioeconomic level, school characteristics, school transportation, paid work, smoking, use of alcohol and body mass index. |

17. Barbosa et al. (2012) |

The prevalence of insufficiently active participants was 50.5%. |

18.Coelho et al., (2012) |

The prevalence of insufficiently active participants was 60.46%. |

19.Silva Jr. et al. (2012) |

The prevalence of sedentary participants was 40.8%. |

20.Bergmann et al., (2013) |

The prevalence of physical inactivity was high 68%. |

21.Moraes et al., (2013) |

The prevalence rates of physical inactivity were 57.95% among girls and 56% among boys. |

22.Leites et al., (2013) |

The prevalence of insufficient physical activity was 70.5% (boys: 58.9% vs. girls: 81.9%). |

Table 3. Main results of the studies included in this systematic review

Socioeconomic level is strongly associated with physical inactivity (Alves et al., 2012; Dumith et al., 2012; Guedes et al., 2012). Three studies found that high socioeconomic level was a risk factor for physical inactivity (Alves et al., 2012; Dumith et al., 2012; Guedes et al., 2012). Only the study by Silva et al. (2010) found that low socioeconomic level was a risk factor compared to an intermediate socioeconomic level.

Four studies associated physical inactivity with time spent watching television (TV), which is considered one of the components of sedentary behavior. According to the studies, the adolescents who watched TV more than one hour per day exhibited more sedentary habits and greater odds of being inactive, with considerable increases in the prevalence of physical inactivity (Alves et al., 2012; Souza et al., 2010).

Assessment of methodological quality

Tables 3 and 4 describe the results corresponding to the assessment of the methodological quality of the studies included for systematic review. The cohort study met five out of the six criteria previously established to assess the methodological quality of the studies. In the case-control study by Lippo et al. (2010), data corresponding to some of these criteria were not informed. Only three among the cross-sectional studies met all the criteria previously established to assess the methodological quality of the studies (Alves et al., 2012; Fermino et al., 2010; Leites et al., 2013). However, all the cross-sectional studies sought to answer a clear and well-focused question, to describe the assessed outcomes in a valid and standardized manner and to present and discuss the results in a clear manner. The sample was representative in most cross-sectional studies; the exception was the study by Silva et al. (2010), in which the sample size was smaller compared to the remainder of the studies. On the other hand, only one study reported the inclusion and exclusion criteria for selecting participants (Tenório et al, 2010.), And only four studies reported losses and exclusions (Alves et al, 2012; Fermino et al, 2010; Leites et al, 2013; Silva et al, 2010), however the study of Santos et al. (2010) do not report this criterion. According to the criteria selected to assess study quality, the quality of all the studies might be rated as good.

Items assessed |

3 |

14 |

Clear, well-focused and adequate question |

Y |

Y |

Sufficient follow-up duration |

N |

Y |

Representative sample |

Y |

Y |

Participants’ selection controlled for possible confounding factors |

NI |

Y |

Outcomes assessed by researchers blinded to exposure |

NI |

NI |

Loss to follow up |

N |

Y |

Caption: NI, not informed; Y, yes; N, no.

Table 3. Assessment of the methodological quality of the cohort and case-control studies included in this systematic review

Items assessed |

1 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

Clear, well-focused and adequate question |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria to select participants |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

NI |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Outcomes assessed in a valid and standardized manner |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Losses and exclusions |

Y |

NI |

Y |

NI |

NI |

NI |

N |

N |

NI |

NI |

N |

NI |

Y |

NI |

NI |

NI |

N |

NI |

N |

Y |

Results clearly presented and discussed |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Caption: NI, not informed; Y, yes; N, no

Table 4. Assessment of the methodological quality of the cross-sectional studies included in this systematic review

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present study was to analyze the evidence available assessing the prevalence of physical inactivity among Brazilian adolescents by means of a systematic review of observational studies. The procedures for the search and selection of studies allowed identification of factors associated with the investigated subject.

During human development, adolescents undergo socioeconomic, biological (age, gender), sociocultural (incentives from family, friends, teachers, public policies) and psychological (motivation, lack of interest, knowledge, self-image, perception) processes that enable them to develop healthier physical activity habits and lifestyles for adulthood (Campagna & Souza, 2006; Sallis et al., 2000; Seabra et al., 2008).

According to the recommendations by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM, 2013), adolescents should play games and engage in sports and exercise corresponding to moderate or vigorous physical activity 60 minutes per day. Most studies included in the present review classified adolescents as insufficiently active using the cutoff point of <300 min/week, which agrees with studies conducted in Pelotas, Rio de Janeiro and the state of Santa Catarina (Bertoni et al., 2009; Castro et al., 2008; Farias et al., 2009). Based on those recommendations, the results of the present review indicate that a considerable number of adolescents are insufficiently active, with a 59% prevalence of physical inactivity in the investigated population. Only three studies reported relatively lower prevalence rates: 35.2% (Lippo et al., 2010), 40.8% (Silva et al., 2012) and 41.8% (Fermino et al., 2010). These results agree with those of the studies by Cano et al. (2011), Melo et al. (2009), and Farias et al. (2009), in which the prevalence rates of physical inactivity among adolescents were 28,5%, 31%, 39.2% and 36.5%, respectively.

The literature shows that questionnaires are highly practical and easy to perform and to apply in epidemiological studies (Armstrong & Welsman, 2006), however, the wide variety of questionnaires available to assess the physical activity level is a cause for concern among the scientific community, as they use different measurements and cutoff points, which might account for the variability in the results, as the high prevalence of physical activity is observed in Fortaleza (67.4% and 65.1%), might be largely accounted for by the fact that cutoff points lower than the ones established for adolescents were used (Freitas et al., 2010; Vasconcelos et al., 2010). Upon analyzing the prevalence of physical inactivity per gender, most studies included in this review found that girls are more sedentary than boys (Alves et al., 2012; Barbosa et al., 2012; Beck et al., 2011; Campos et al., 2010; Dumith et al., 2012; Fermino et al., 2010; Freitas et al., 2010; Guedes et al., 2012; Leites et al., 2013; Lippo et al., 2010; Moraes & Falção, 2013; Rivera et al., 2010; Romero et al., 2010; Santos et al., 2010; Silva et al., 2010; Silveira & Silva, 2011; Souza et al., 2010; Tenório et al., 2010). These findings corroborate with the researched literature, in which, it is emphasized that female adolescents do not reach the physical activity recommendations, being more inactive than male adolescents (Farias et al., 2012; Oviedo et al 2013.).

However, that finding might be understood based on some behaviors that appear in adolescence: girls start discovering their own bodies upon the appearance of menarche and become more critical, reflective and independent, with greater social integration capacity. Those facts might influence girls to seek passive activities with a cultural or cognitive focus to satisfy their needs.

Age is also associated with increased or decreased physical inactivity among adolescents. In the adjusted analysis study Bergmann et al. (2013), noted that older adolescents tend to be inactive; these results corroborate with the study of Ruiz et al. (2011) the average level of physical activity was lower among older European adolescents (2.4% per age group increase). Specifically in Spain, it was identified that adolescents aging between 17-18 years are more inactive than adolescents with 11-12 years old (Ramos et al., 2012).

Studies conducted in Brazil have demonstrated that the level of physical activity decreases over time among older boys, and a greater tendency to sedentarism was specifically detected among youths aged 17 to 18 years old (Dumith et al., 2011; Oehlschlaeger et al., 2004), and a possible explanation for That decline might be due to the youths’ entrance into the labor market, lack of time and dissatisfaction with the practice of sports at school (Leites et al. 2013). Similar results were found in the study of Seabra et al. (2008), which suggests that the boys are identified with a work identity, which facilitates their active inclusion in society, resulting in their partaking in more vigorous activities, while girls are oriented toward home- and family-related tasks.

Seabra et al. (2008) observed that some social models might maintain or change the behavior of adolescents, as occurs in the case of children. The family operates as a generator of values, norms and behaviors, as a given degree of autonomy begins to prevail among adolescents that serves to motivate them to detach themselves from their parents. In this contexts the literature describes some barriers that contribute to the lower levels of physical activity exhibited by girls, such as “being lazy” (51.7%), “not having friends” (46.8%) and attitudes such as “I’d rather do something else” (47.8%) (Santos et al., 2010).

Taking those social aspects into consideration, one might say that adolescents lose the motivation to participate in sports as they become older because they enter a new stage in life, characterized by new sources of interest, motivations, experiences, behaviors and different personality traits, which, together with their development, might exert negative influences on the regular performance of physical activity.

Additionally, economic determinants are highly relevant in studies on physical inactivity. The results of this study indicate that physical inactivity is strongly characteristic of particular economic classes (low and high). According to Seabra et al. (2008), there are several methods for assessing socioeconomic status based on either family income or the educational level or occupations of the family members, thus, having a low (Janssen et al., 2006; Lämmle et al., 2012; Moraes et al., 2009; Silva et al., 2010; Tammelin et al., 2003) and high socioeconomic level (Dumith et al., 2012; Gonçalvez et al., 2007; Guedes et al., 2012) are a risk factor for physical inactivity among adolescents.

It is believed that adolescents with low purchasing power exhibit poorer odds of attending gym academies or private clubs for exercise, which might contribute to their poor habits relative to physical activity. Although those adolescents have greater chances to walk or cycle to school, parks, and other places, those activities are not sufficient for them to achieve the activity levels recommended for health maintenance. Although individuals from favored social classes have more financial resources, which might possibly favor the practice of physical activity, the opposite is true, as new technologies, such as video games and computers, and the use of motor vehicles to go to school contribute to increases in sedentary behavior. Sedentary behavior, screen time (i.e., time spent watching TV, playing video games, and using the computer) in particular, is one further relevant indicator of physical inactivity. In this review indicated that adolescents spent too much time watching TV (≥ three hours) (Coelho et al., 2012). Those findings agree with the results of other studies, which reported a dramatic exposure of adolescents to TV increasing weekends (Abarca-Sos et al., 2010; Gómez et al., 2002; Hallal et al., 2010), and high exposure to TV might be strongly associated with smoking, poor physical fitness and the development of unhealthy dietary habits, which lead to overweight and high cholesterol levels in adulthood (Hallal et al., 2010; Hancox et al., 2004).

One study in the present review further detected that girls are more prone to becoming inactive as a result of the time they spend watching TV; that finding is corroborated by the results of Camelo et al. (2012). Additionally, the study by Ussher et al. (2007) found that boys attending English schools spent more time watching TV everyday (> three hours) compared to the girls, exceeding the recommended maximum daily screen time of two hours (AAP, 2015).

CONCLUSION

The present review found that the overall methodological quality of the included studies was good. The results indicate that most studies had been performed in the Northeastern and Southern regions of Brazil. Such a concentration of the studies in two regions leads one to suggest that a larger number of studies ought to be conducted in other geographical regions, as the availability of various analyses would allow researchers to obtain a broader understanding of the prevalence of physical inactivity in Brazil, mainly longitudinal studies that reveal behavioral changes related to sport and physical activity of adolescents.

The results further showed that relative to their design, most studies included in this review were cross-sectional, followed by cohort and case-control studies, and used indirect measurements of physical activities based on the application of questionnaires, which leads us to suggest further studies accompanying the support and use of direct measures, so as to achieve a gold standard when it concerns the assessment of physical activity in adolescents.

The prevalence of physical inactivity was above 50% in most studies, though the rates corresponding to girls were higher than those corresponding to boys. It is worth observing that socioeconomic, psychological and social factors might exert both direct and indirect influences on the level of physical activity of Brazilian adolescents. In addition, analysis of the studies conducted in Brazil indicates that the prevalence of physical inactivity is increasing considerably among adolescents.

This revision has identified that these indexes has increased over the years, considering what is going on since 2010, these changes of physical inactivity has not decreased in general, which corroborates to update the data of this variable, and get even more effective strategies to combat physical inactivity.

These findings corroborate the need for concern with and reflection on this population in the search for a solution to overcome this problem.

Based on the findings described above, one might suggest that studies ought to be performed in other Brazilian areas, particularly longitudinal studies, to identify changes in the behaviors related to physical activity and sports among Brazilian adolescents. In addition, this finding corroborates the need for concern and reflection by the family, school and government entities in the pursuit of solutions to this situation, suggesting the development and implementation of public policies allowing for the implementation of new projects for extracurricular school activities ought to be developed and applied to promote the practice of physical activity and sports based on an earlier survey of adolescents about the preferences of activities, promoting healthy lifestyles.

REFERENCES

Recepción 03-03-2015

Aprobación: 02-11-2015