Introduction

Leptospirosis is a disease of worldwide distribution caused by the bacteria Leptospira. Leptospirosis affects domestic animals, mainly dogs, cattle, sheep and pigs. It also affects wildlife, especially carnivores, rodents and marsupials in captivity. In humans, leptospirosis is acquired from an animal host. Rodents have been shown to play a key role in the transmission cycle [1]. The tropics and subtropics have characteristics such as soil moisture, temperature, rainfall, areas of potential flooding and areas with poor hygienic sanitary conditions that meet the perfect conditions for the presence of the bacteria, its maintenance and its transmission. Leptospirosis can manifest in humans as a simple cold, however, it can also be so severe that it leads to death [1,2]. In its typical form, it shows up as a non-specific systemic disease characterized by fever, myalgia and headaches. It is often confused with other illnesses, such as influenza, dengue or malaria [3-5]. Because it does not have typical symptomatology, diagnosis by laboratory or epidemiological link is essential.

The average annual incidence for the Americas region is 12.5 per 100,000 people, ranging from 0.1 to 306.2 in the period between 1970 and 2009, with a mortality rate of over 10% [6]. In the Americas there are information gaps in relation to the disease’s epidemiology and, therefore, the disease’s real impact. In Colombia, leptospirosis has been mandatory to report to the System of Epidemiological Surveillance of the Colombian National Institute of Health (SIVIGILA by its Spanish acronym) since 2007. The first documented case of human leptospirosis occurred around 1957, while the first epidemic in Colombia occurred in the country’s Atlántico department in 1995, with a case fatality rate of 17% among the confirmed cases [7]. In Colombia, the ELISA technique is used as a screening test. All cases that are indicated to be positive via this test are then sent to the National Institute of Health (INS) reference laboratory to be confirmed by a Microscopic Agglutination Test (MAT), which is the gold standard recommended by the World Health Organization [8,9].

Reports of leptospirosis in Colombia must be analyzed from an epidemiological perspective in order to have a better understanding of the disease’s presentation. It is crucial to determine the distribution, incidence and lethality of the disease. Adding to work already done focusing on human leptospirosis from an epidemiological perspective in Colombia [10], our work presents an analysis from three different spatial scales with additional associations with variables of sex, age, place of origin and geographical region.

The objective of this study was to perform an epidemiological analysis of human leptospirosis in Colombia at the national, departmental and municipal level in the period between January 2007 and December 2015.

Methodology

An ecological study of temporal trend and spatial distribution of leptospirosis cases reported to SIVIGILA between January 2007 and December 2015 was conducted. The study was conducted in Colombia, a country located in the north-west of South America that has a population of 45.5 million people [11], according to the preliminary results of the census held by the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) in 2018. Administratively, Colombia is divided into 32 departments and 1,032 municipalities. In the present study, data was grouped into 3 spatial scales: national, departmental and municipal.

The leptospirosis data for the years 2007 to 2015 [8] was obtained from the SIVIGILA databases, which contain all suspected cases as defined by the Public Health Surveillance Protocol. The epidemiological analysis of the disease included cases that were confirmed by laboratory and cases that were confirmed by epidemiological link. Confirmation by laboratory is done with the MAT technique with a result greater than 1:400 in single sample or seroconversion in paired samples with a 10 to 15 day period between them [8]. Confirmation by epidemiological nexus is done by taking cases confirmed by laboratory and linking people, a time and place to the source of the infection identified in the confirmed case [8].

Distribution of cases among sex, age groups, municipality of residence and area of residence (urban, rural) was obtained, and the disease’s lethality was calculated. The symptom onset date was used for the temporal analysis of cases and the municipality of residence was used for the spatial analysis. The monthly annual cycle of cases for Colombia was estimated. To estimate the annual cycle, the monthly average cases was obtained and plotted with its respective standard error. The total and annual incidence rates per 100,000 inhabitants were calculated at the national, departmental and municipal level. In order to estimate the total incidence rate, the total number of cases of the study period and the average population of the study period were obtained. The incidence rate was calculated by taking the number of cases and dividing it by the population, then multiplying the result by 100,000. To calculate the annual incidence rate, the number of cases for each year and the average population of the same year were compiled. The population for each year and for each municipality of the country was obtained from DANE, with projected populations based on the census carried out in 2005 [12]. The case fatality rate was calculated at the national level by dividing number of deaths by number of confirmed cases for each year. The proportions according to variables of interest were compared using the Chi square test with Yates correction and with a significance level of 5%. Case distribution maps were developed at the municipal level. To identify areas of higher case concentration (hotspots), a kernel estimator was used [13].

The free software R version 3.5.0, from the R Foundation, was used to perform epidemiological data analysis. For spatial representation, ArcGis version 10.3 from ESRI was used. Data regarding leptospirosis cases were not acquired through interaction with individuals and contained no identifiable private information, so were therefore considered exempt from review by an Ethics Board (following the WMA Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects).

Results

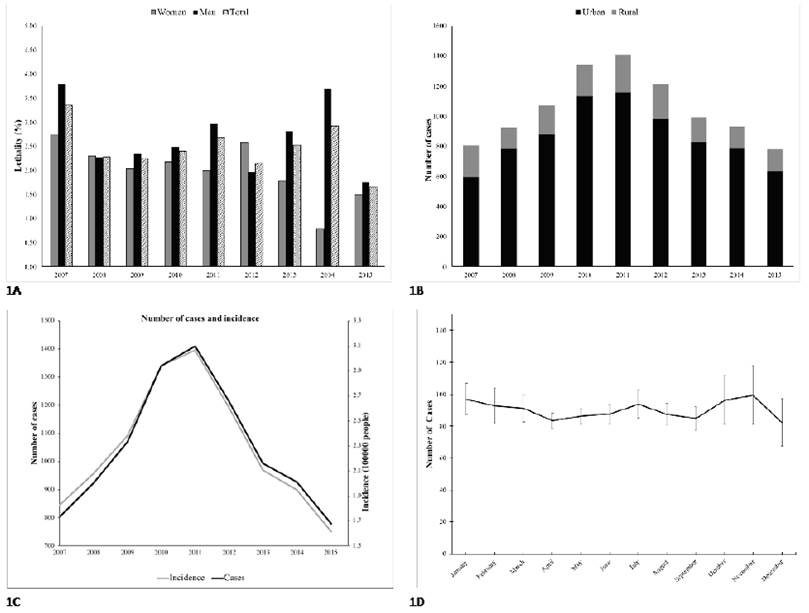

For Colombia, 23,994 suspected cases of leptospirosis were identified during the period between 2007 and 2015, of which 9,449 (39.4%) were confirmed by laboratory or epidemiological link. The origin of the confirmed cases was mainly from urban areas (82.4%), showing that, over the years, the distribution of this disease has been significantly disproportionate (p value = 0) (see Supplemental material 1, Figure A). Regarding the distribution by sex, there were 6,505 confirmed cases in men (68.87%) and 2,943 in women (31.13%) (p ≤ 0.001) (see Supplemental material 1, Figure B). The lethality was higher in men than in women, with 2.66 and 2.04 respectively (see Supplemental material 1, Figure B). The age group with the most cases each year was 14 to 34 years in both sexes (p ≤ 0.001). For the period from 2007 to 2015, the incidence in Colombia varied between 1.62 and 3.06 per 100,000 inhabitants (2015 and 2011 respectively). A peak incidence can be observed between 2010 and 2012 (see Supplemental material 1, Figure C). In the annual cycle of the monthly total cases, the majority are concentrated in October and November and do not indicate a marked seasonal pattern (see Supplemental material 1, Figure D).

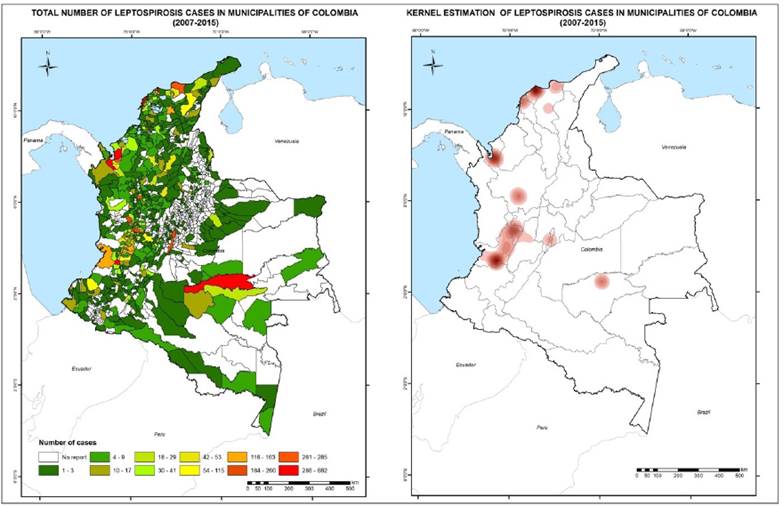

Kernel estimation identified four areas of concentrated cases in the national territory located on the Caribbean coast, in the north-west and center of the Antioquia department, Valle del Cauca, the Colombian coffee region and Guaviare (see Figure 1, right).

The department with the highest number of confirmed cases of leptospirosis in the study period was Valle del Cauca (21.5% of the total for the country), followed by Antioquia, Atlántico, Bolívar and Risaralda. Vichada was the department with the lowest number of confirmed cases (2 cases). The total incidence rate per 100,000 inhabitants at the departmental level ranged from two, for the department of Arauca, to 465.4, for the department of Guaviare. Results of the total number of cases and total incidence for each of Colombia’s 32 departments are presented in Table 1. The annual incidences and annual number of cases at the departmental level are presented in Supplemental material 2.

Table 1:

Total number of leptospirosis cases and total incidence per 100,000 people at the departmental level.

At the municipal level, the highest number of cases occurred in the city of Cali, which had 682 confirmed cases during the study period. No cases were reported for some municipalities, while other municipalities had between one and two cases during the study period.

As for the total incidence per 100,000 inhabitants at the municipal level, the highest incidence occurred in Pueblo Rico (Risaralda), followed by Sabanas de San Ángel (Atlántico), San José del Guaviare (Guaviare) and Puerto Arica (Amazonas). Other incidences were found distributed as follows: two municipalities with incidences between 300 and 400; six municipalities between 200 and 300; 22 municipalities between 100 and 200; 47 municipalities between 50 and 100; 309 municipalities between 10 and 50; and 211 municipalities with less than 10. The annual incidence at the municipal level varied between 0 and 1599.7 per 100,000 people. The 30 municipalities with the highest number of cases of leptospirosis and with the highest incidences are shown in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively.

Table 2:

Total number of leptospirosis cases in selected municipalities.

Table 3:

Total incidence of leptospirosis per 100,000 people in selected municipalities.

The distribution of total cases of leptospirosis in each of the municipalities of Colombia is shown in Figure 1, left. White indicates that the municipalities did not report cases to the system during the study period. For the municipalities that reported cases to the system in the study period, the total cases vary from 1 (shown in green) to 680 (shown in red). Some municipalities on the Caribbean and Pacific coasts and in the Colombian coffee region, and one municipality in the Amazon, presented a high number of cases.

Discussion

In Colombia, there were 9,449 confirmed cases of leptospirosis between 2007 and 2015, with annual incidence peaks in 2010, 2011 and 2012. Cases were distributed heterogeneously in all of the country’s departments. At the municipal level, there was a large variation in the annual incidence, ranging from zero to 1,599 per 100,000 inhabitants.

In the period studied, Colombia had an average annual incidence rate of 2.3 per 100,000 inhabitants, with a minimum of 1.62 in 2015 and a maximum of 2.94 and 3.06 in 2010 and 2011 respectively. The annual incidence rates found in Colombia are within what the World Health Organization’s Leptospirosis Burden Epidemiology Reference Group (LERG) estimates to be an endemic level for a humid tropical equatorial country. The years with the highest incidences coincide with the La Niña event that strongly affected the country in late 2010 and during 2011, causing increased rain and historical floods [14]. In recent years, the La Niña event has been indicated by several authors to be an important factor that influences leptospirosis in Colombia [15,16].

The reported incidences for countries in the region vary. In Brazil, the annual incidence for the period from 2010 to 2014 was 2.1 per 100,000 inhabitants; in Mexico, it fluctuated from 0.04 to 0.4 per 100,000 inhabitants between 2000 and 2010; in Peru, the incidence has increased in recent years with reports of one per 100,000 inhabitants in 2011, 6.3 in 2012 and 8.6 in 2013; in Ecuador, leptospirosis is reported to be a growing problem, with an average annual incidence of 0.5 cases per 100,000 inhabitants between 1996 and 2005; in Venezuela, there is only a report for the years 2004 and 2005 that indicates an incidence of 0.4 per 100,000 inhabitants [17-21].

Although countries in the region do not have consistent yearly data for the incidence of leptospirosis, the numbers reported in Venezuela, Ecuador and Mexico are still lower than those in Colombia, and are similar to those found in Brazil.

Our results show that the majority of cases of leptospirosis in Colombia come from urban areas, representing 82% of the total. Leptospirosis is a disease that can occur both in the countryside and in urban environments, but is more prevalent in the latter [22,23]. The most frequent presentation of this disease in urban areas is due to the most common forms of human infection, including synanthropic rodents, overcrowding and precarious sanitation circumstances, which are typically found in cities [24]. At present, the majority of the population of Colombia lives in urban areas, which also contributes to the fact that the majority of cases come from these environments. Urbanization is a triggering factor for the increase in cases worldwide, affecting both developed and developing countries, with the significant difference that the latter have less resilience capacity to face healthcare problems of populations settled in places with poor infrastructure and with poor hygienic sanitary conditions [23]. In Colombia, we found that the population is mainly distributed in cities where favorable conditions exist for increased leptospirosis transmission.

Regarding distribution by sex, our results indicate that, in Colombia, the proportion of cases of leptospirosis in men is significantly higher than in women. Similar results have been reported in several European countries such as Germany, Italy, Bulgaria and Slovakia, and in Brazil [25,26]. In Colombia, a study was conducted in Turbo, a municipality in the department of Antioquia, which showed that 67.6% of cases there were male [27]. Our study’s national results complement information on the increased presentation of leptospirosis in males in all age groups. Physiological factors have been ruled out as the cause of an increased number of cases among men [28]. We understand that the increased presentation of leptospirosis in males is attributed to behavioral and occupational factors.

Leptospirosis is associated with some agricultural occupations such as rice, yam, sugar cane and banana growers [3,29]. These activities have been traditionally performed by men and are also part of the rural Colombian economy. In this study we did not perform an analysis of occupational activities since the information for this variable was incomplete in the SIVIGILA databases. However, we assume that economic activity has an impact on the occurrence of leptospirosis, in particular in the Urabá region (Antioquia), where the present study found a hotspot for the disease in Colombia, since there is extensive banana and plantain farming in the region.

Some pleasure and recreational activities are gaining significance in relation to the presentation of leptospirosis worldwide [30-32]. In Colombia, bathing in rivers is part of the culture in warm areas. A study conducted in the Urabá area found that bathing in rivers is a risk factor for leptospirosis [27]. We infer that this practice may be associated with some of the hotspots of Urabá and Valle del Cauca.

The leptospirosis lethality found in this study was 2% per year at the national level. This lethality contrasts with countries like Brazil where the lethality is around 9% [17]. High fatality rates of leptospirosis suggest that the cases being confirmed are the severe cases and milder clinical forms are not being reported. Even though cases may not be reported in certain countries, the burden of the disease still affects those countries’ public health. This low lethality in Colombia is a sign that the surveillance system is efficient at notifying based on diagnosis, detecting milder cases that usually represent the majority of cases.

We found six hotspots of leptospirosis in Colombia, located on the Caribbean coast, in the north-west and the center of the department of Antioquia, Valle del Cauca, the coffee region and the department of Guaviare. Previous studies identified incidence hotspots for Colombia, two of which coincide with the hotspots found in our study: north-west Antioquia (Urabá region) and Guaviare department [10]. It is important to note that the capital of the department of Guaviare, San José del Guaviare, has had an active epidemiological surveillance program since 2004, which tracks and diagnoses febrile cases that present within the health system. Moreover, in the Urabá region located in the north-west of the department of Antioquia, there is also an active surveillance program as the result of a commitment by the local authorities and institutions located in the area [33,34]. These programs are unique in Colombia and, therefore, the number of reports for these municipalities and regions are greater than those of its neighbors. Hotspots are places where there is a greater density of cases when comparing the number of cases with the municipality’s area. Higher rates of incidence of cases do not always coincide with a higher density of cases, although it should also be considered that a higher density of cases could correspond to regions of greater clinical suspicion and better notification of the disease.

At the departmental level, 85% of Colombia's total cases for the period between 2007 and 2015 are concentrated in 10 of the country's 32 departments. The 10 departments are: Valle del Cauca, Antioquia, Atlántico, Bolívar, Risaralda, Magdalena, Guaviare, Cundinamarca, Tolima and Cauca. In turn, these departments also have the highest incidences in the country. This finding is an important tool in the efforts to optimize the resources of epidemiological surveillance programs since these could be used as sentinel or early-warning departments to establish the morbidity situation of leptospirosis in Colombia.

In terms of annual rates, there is a large variation in incidence rate, both when comparing different departments in the same year and when comparing a single department in different years, although a clear trend is not observed (see Supplemental material 2, Table 2].

In some departments there is a low number of cases, or even no cases. This low number of cases could be due to the fact that surveillance programs still do not report all cases that occur in their territory and do not necessarily reflect the risk of leptospirosis infection.

When comparing the annual departmental incidences of Colombia with those of the different states of Brazil (between 2010 and 2014) and Mexico (between 2000 and 2010) we find that, in general, Colombia's figures are higher than those presented in these two countries, even when considering the same years. This comparison at the departmental level contrasts with the results obtained at the national level, in which Colombia has similar incidences to these countries. This finding reaffirms the importance of the scale factor in analyzing a disease’s epidemiological data.

At the municipal level, we found that the 30 municipalities with the highest number of cases were located within the focal points identified as hotspots and were concentrated in Valle del Cauca and Antioquia. The incidence of the majority of the country’s municipalities was between 10 and 50 per 100,000 inhabitants. With the exception of San José del Guaviare, whose surveillance system is active, the municipalities with the highest number of cases in Colombia belong to large cities with large populations. In contrast, the highest incidences occur in small municipalities on the Caribbean coast, and in the center, west and south of the country, indicating that the risk of leptospirosis is distributed throughout the Colombian territory (see Supplemental material 3 for annual incidence and annual number of cases in selected municipalities).

Implications for epidemiological surveillance

Leptospirosis is a disease that is difficult to diagnose via both methods of diagnosis: laboratory confirmation and differential diagnoses. Laboratory confirmation requires two paired samples with an interval of 10 days. Frequently, patients do not return to their healthcare provider to get the second sample taken for confirmation. It is estimated that, for the region of Urabá, the number of patients who return for the second sample is close to 30% [33]. In addition, co-infection of dengue and leptospirosis has been documented in patients and in several regions of Colombia, and even in other countries [8,35,36]. Leptospirosis occurs in areas with a high incidence of dengue, making it difficult to detect other diseases as some clinical forms of leptospirosis can be confused with dengue. In this way, dengue acts as an umbrella disease under which many febrile cases are diagnosed and are not confirmed, thus masking other diseases such as leptospirosis. Based on a study conducted in Fortaleza, Brazil, the authors consider the possibility that, in endemic areas for dengue and leptospirosis, approximately 20% of suspected dengue cases may be leptospirosis [37]. All this leads to an underdiagnosis of leptospirosis, contributing further to ignorance of the disease’s real extent in Colombia.

Limitations of the study

In this ecological study, the incidence rates were analyzed at different geographical scales corresponding to political divisions and over time. The socioeconomic and demographic heterogeneity of the spatial clusters (departments and municipalities) can contribute to inaccuracies in the disease’s risk assessment.

The present study has used secondary data obtained from official databases that may undergo revision, which may affect consistency. Also, since the notification system is relatively new (since 2007), there are expected limitations in monitoring and difficulties such as the standardization of information flows, the omission of data in some of the variables of the notification form, and the absence of notification by some territorial entities. Although there are improvements in the system, there are still municipalities that fail to notify. These municipalities are concentrated in the departments of Vichada, Guainía, Vaupés, Arauca and Meta. There is uncertainty as to whether these municipalities did not actually register cases of leptospirosis during the study period because they belong to departments that historically have been neglected by the central government and face budgetary difficulties.

Conclusions

The notification of leptospirosis in Colombia is distributed progressively, that is to say, it has increased over the years throughout the national territory between 2007 and 2015. Some departments have higher incidences, such as Guaviare, Risaralda and San Andrés, while others have higher numbers of cases, such as Valle del Cauca, Antioquia and Atlántico. At the regional level, there are areas of concentration of cases in different regions on the Caribbean coast and in the north-west and center of Antioquia department, Valle del Cauca, the coffee region and the department of Guaviare. Despite improvements in the reporting system, there are still departments with few or no case records, especially in the Eastern Plains and the Amazon. In the country's municipalities, incidence rates of leptospirosis range from zero to 1,597.6 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, indicating that there are areas at high risk for the disease. The low lethality found in Colombia suggests that the surveillance system has detected mild cases of the disease.

It is suggested that more detailed research on factors associated with the occurrence of cases and the circulation of the bacteria is carried out. This epidemiological analysis of the leptospirosis situation in Colombia responds to a worldwide need for more accurate and real information on this significant zoonotic disease.