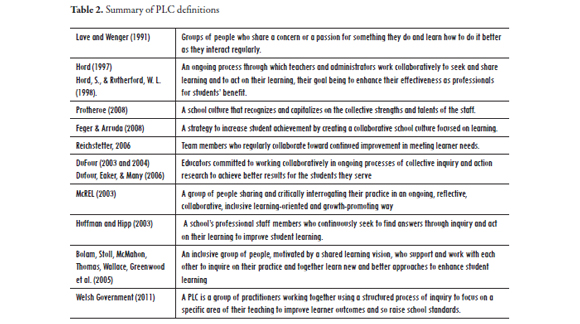

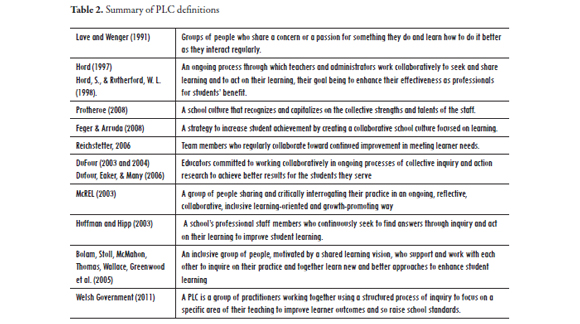

These definitions share a vision of group work, continuous improvement, common interest, collaborative work, and mutual goals. In this article, I conceive a PLC as a group of professionals,

in this specific case in the field of education (professional), who gather together to share experiences and undertake research (learning),

resulting in improved practices in the short term

and in influence on policy makers in the long term

(community).

The literature on PLCs and learning often

mentions the following five core organizational

principles:

1. Supportive and shared leadership

2. Collective creativity/responsibility

3. Shared values and vision

4. Supportive conditions

5. Shared personal practice

Supportive and shared leadership.

Any change in the academic community

demands the involvement of its administrators,

whose leadership engages staff in professional

development activities. Thus, Caine and Caine

(2000) say that PLCs develop teacher-leaders.

While administrators share knowledge, decisionmaking

and provide opportunities for exchanging

ideas, teachers increase their leadership capacities

and use their experience, practices and inquiries to

construct knowledge.

Collective creativity/responsibility.

Louis and Kruse (1995) report that a learning

community is constituted by people from diverse

backgrounds who conduct a reflective dialogue

about students, teaching and learning. They take

part in various tasks that demand proactivity

and the rigor to pursue a goal. In this article the

reflective dialogue is suggested around research

practices. As a way of example, by organizing

online collaborative groups participants may find

a place in the academic world.

Shared values and vision.

According to Reichstetter (2006) and Huffman

(2003), participants in PLCs have in common

the vision of commitment to improvement. In

fact, special attention is devoted to how not just students but also the community participants can

learn. Additionally, as with any organization, the

vision and mission are stated and are followed by

all the members.

Supportive conditions.

Offering space and time for gathering together

and setting clear conditions for operationalizing

the network are two pillars to guarantee the

accomplishment of goals. Support should come

from the inside, meaning the learning community

itself, and from the outside, meaning the current

affiliation of participants.

Shared personal practice.

Teachers work and learn together as they

continually evaluate their practices and the needs,

interests and skills of their students (McREL,

2003). The Colombian educational system would

benefit from a learning community like the one described in this paper since it allows educators

from different educational contexts, backgrounds

and areas of expertise to work together toward a

common goal. Furthermore, knowing what others

are doing in other contexts and understanding

how colleagues address common issues may enrich

individual methods.

Unlike other forms of professional development,

PLCs give each member the chance to be a leader,

which means participants are not mere receivers of

knowledge but also knowledge producers. The five

principles mentioned before provide the path to put

into operation any PLC and lead to research on the

benefits, characteristics and impact on students´

performance as the Center for Comprehensive

School Reform and Improvement (http://www.

centerforcsri.org/plc/) explains.

Stoll, Bolam, McMahon, Wallace, and Thomas

(2006) argue that due to greater job satisfaction,

shared responsibility, and reduction of isolation, the main benefit concerns the impact on students’

performance. Many educators face the same

problems or have the same academic interests, but

take diverse approaches to common situations.

In consequence, a PLC is a space where different

visions of the world may be shared and thus

modified and improved. Although there is

recent evidence on PLCs, Stanley (2011) reports

teachers working together dates back to 1973

with the study on “Federal Programs Supporting

Educational Change” and a 1980 study by Joyce

and Shower. In this report Rand conducted a twophase

study to spread and introduce best practices

in US public schools.

Other evidence of how PLCs work emerges and

benefits both primary and secondary education

is presented by some school districts. South

Elementary in Missouri (2007) and Boones Mill

Elementary in Virginia (2002) reported student

improvement, the former by implementing

common assessment in their literacy instruction

and problem-solving for at-risk learners, the latter

by organizing research teams of teachers who

looked for measurable student achievement goals.

Other examples at the middle school level are the

case of Lewis and Clark Middle School in Missouri

(2003) and of Woodsedge Middle School in Texas

(2003). In the first case participants evaluated data

and later implemented an approach that included

professional development. In the second case,

educators designed curricula to help low achievers.

In both cases results showed student improvement

and collaborative research by teachers. At the

high school level and in 2007, a school in Bogotá,

Colombia did a study on how bilingual education

was implemented in some schools of the same city.

Results showed different understanding as to what

the concept of bilingual education entails.

Other reports refer to the impact of PLC. In

2001 the National Staff Development Council

(NSDC) stated that “the most powerful forms

of staff development occur in ongoing teams

that meet on a regular basis . . . [These] learning

communities or communities of practice operate

with a commitment to the norms of continuous

improvement and experimentation and engage

their members in improving their daily work to

advance the achievement of school district and

school goals for student learning.” (p. 1)

The Department for Education and Skills (DfES),

the General Teaching Council for England

(GTCe) and the National College for School

Leadership (NCSL) from January 2002 to

October 2004 also funded a project entitled

Creating and Sustaining Effective Professional Learning Communities (EPLC). Their main

conclusion was that the creation of PLCs is

worth pursuing for promoting school and systemwide

capacity building. They identified eight

characteristics: shared values and vision, collective

responsibility for pupils’ learning, collaboration

focused on learning, individual and collective

professional learning, reflective professional

inquiry, openness, networks and partnerships,

inclusive membership and mutual trust, respect

and support. PLCs change over time while also

providing a model to follow. The above study

gives more insights for this paper, not only because

it explains the key factors for execution but also

because it gives some general recommendations

for future implementations. These conclusions

resulted from answering five broad questions:

•What are professional learning communities and how has the concept developed?

• What makes professional learning communities

effective?

• What processes do professional learning

communities use, and how do they contribute to the development of an effective professional

learning community?

• What other factors help or hinder the creation and development of effective professional learning communities?

• Are professional learning communities

sustainable?

Other studies have focused on the characteristics

of PLCs. In 2008 the Education Alliance at Brown University in partnership with Hezel Associates

conducted a literature review on PLCs using different databases. Besides the questions posed in the previous study, they also asked, “What is known about technology use to facilitate PLCs? What further studies and research is recommended? How do schools/districts support the development of such communities?”

Also worth mentioning is Kline’s (2007) case study

of three teacher communities of practice. The most

relevant aspect of this study has to do with the

conclusion, in which the researcher affirms that

PLCs have a better chance of success if viewed as

voluntary activities rather than mandatory. This

study also supports the idea of inviting teachers by

asking them “What do you do in case…? How do

you handle…? What if….?” This approach results

in increased motivation and the creation of a real

sense of belonging.

Haneda (2006) explains that communities of

practice may be focused on different areas. In her

case she talks about second language research. One

of the main concerns and proposals in this paper

has to do with Haneda´s assertion that group

work and approaches to practices are better dealt

with when addressed from different perspectives

and that interdisciplinary work lets participants

gain knowledge while providing input.

As it can be seen, there are many reports on how

schools implement PLCs. However, less research

has focused on these communities in university

settings. It can be argued that there is a need to foster

the creation of and evaluate the benefits, impact and

caracteristics of PLCs in the Colombian context.

As Huffman and Hipp (2003) argue, the PLC is

“the most powerful professional development and

change strategy available” (p. 4).

PLCs Operationalization – The PLC

Colombian Model

Professional development through PLCs may only occur if there is a change in the paradigm of how professional knowledge is gained. Educators need

to understand that the basis of any improvement

relies on interaction and the exchange of ideas. Of

course, this demands time and cannot be linked

to a certain number of hours. PD is continuous

and calls for commitment if participants want

to succeed. As stated earlier, a community of

this kind only exists because of the sustained

contribution of each participant. In that sense, it

is plausible that educators belonging to different

affiliations, namely private and public institutions

in rural or urban areas, go into partnership.

This section presents the concept and

operationalization of a PLC, including its outcomes.

The PLC in this article has its origins in the heart

of an academic group integrated by educators of

different backgrounds (schools and universities)

who gathered together to do research. It is expected

that the example shown in this section can serve as a

model in Colombia.

To start with, as in any organization, participants

set clear goals and principles to implement. The

former set the purpose and the latter the norms

that result in a sense of belonging.

PLC goals:

1. Support educators and administrators by

means of a national professional community.

2. Create a learning organization where foreign

language educators and administrators in

Colombia cooperate, learn together, and

show research results.

3. Impact national policies through research.

PLC principles:

a. Open-Mindedness: the ability to accept

feedback and apply learning according to each

member´s educational setting.

b. Mutual respect: value and respect cooperative

work by reflecting on different practices.

c. Trustworthiness: dependent and

interdependent loyalty.

d. Supportive leadership: as representatives

of each institution, each member becomes a

leader for his/her community or educational

system.

e. Understanding: build knowledge together.

f. Commitment: ensure the effectiveness of the

PLC through active participation.

g. Collegiality: all members share power,

authority and decision-making that support

the operation of the network.

PLC action plan:

As with all organizations, PLCs require an action

plan. This plan provides the journey to achieve

the established goals and follow the principles

within the organization. One may say there are

two types of actions. The first set of actions has to

do with the operationalization of the community

itself and provides the foundation. The second set

of actions has to do with how to handle the PD

endeavor and sets the work plan. As it was said

before, the proposed PLC is focused on research

practices.

Some of the actions that should be considered are:

• Set when, where and how participants can come together.

• Evaluate the role of technology. It may be vital as a communication channel.

• State the vision and mission of the PLC.

• Register the PLC (for instance on the Colombia Aprende website)

• Set a work plan.

• Identify research lines.

• Pose research projects.

• Study current educational policies and plan to intervene.

PLC outcomes:

PLCs need to establish clear outcomes. These should be evident and measurable.

Examples of desired outcomes include what

Harris and Jones (2010) sum up in three words, “improved learner outcomes,” in addition to

current methodologies:

• Improve practices

• Do research

• Publish for the educational community

• Impact institutional and national policies

In the Colombian context, like any in the world,

these outcomes have a great impact in the academic

community. Sharing let other practitioners learn

from other practices which is another way to

expand the community.

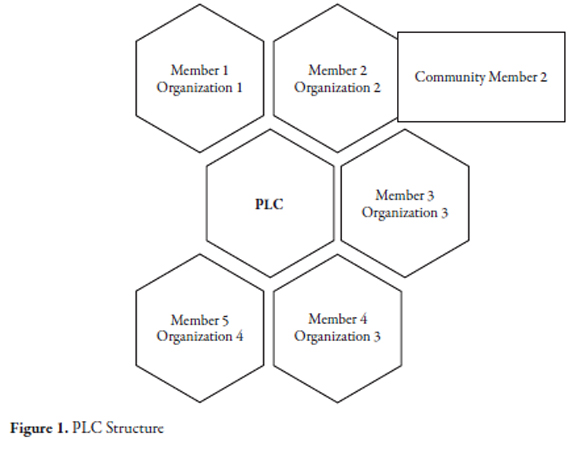

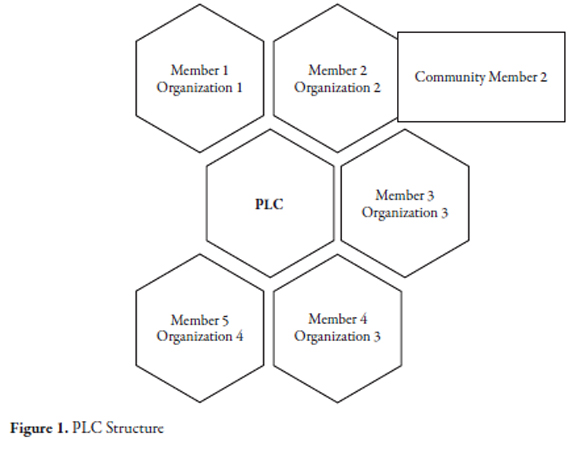

PLC structure.

Although most of the literature on PLCs

suggests teachers be the members of such

groups, administrators, teachers, and teacherresearchers

may also facilitate the creation of these

organizations. In the Colombian context there

is no restriction as to the kind and number of

members; mainly if one considers participants need

to be replicators in their own communities. Figure

1 shows six members as a way of example; however,

there may be as many members as desired.

Figure 1 displays how the PLC brings together

community personnel from various organizations.

Coming from different groups opens the world

of possibilities for academic work. In any case

participants gain knowledge or complete

assignments that involve their communities. In

this example, member three and four come from

the same organization.

Members´ contributions are relevant for a richer

experience. Eaker and Gonzalez (2006) mention

how collaborative work results in specific

products which depending on the plan set forth

for the PLC.

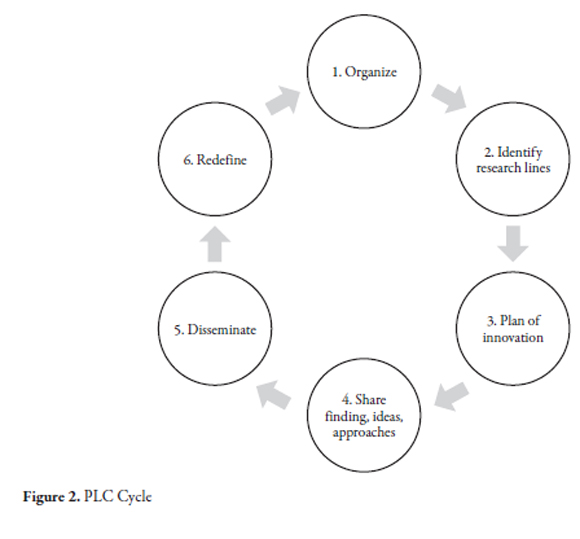

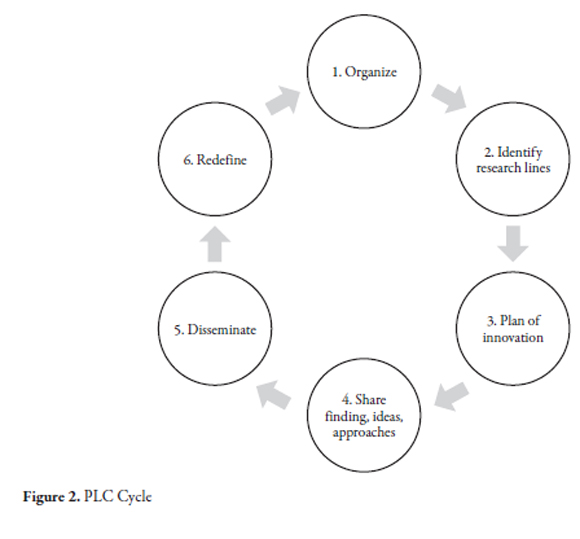

The figure 2 is proposed in light of previous

information and dynamics in many institutions

of the Colombian educational system. Professors,

for instance, are required to do research and

belong to networks where they can both conduct

research and disseminate it. These professionals

usually belong to research groups. However,

this PLC does not necessarily act as a research

group since participants may belong to different

research groups and use the learning gained in

this community as a strategy to expand their

own. It means the PLC acts as a means to gather

researchers together.

Each stage in the cycle is explained as follows:

• Organize groups: call participants to belong

to the PLC. Explain the PLC structure,

goals, norms, principles and expectations.

Establish the group of participants and

group them according to research interests.

Name the PLC coordinator and distribute

leadership responsibilities. Each member acts

as facilitator for his/her area of expertise.

• Identify research lines or areas of interest:

consider the needs in terms of improvement,

and consider the common problems or issues

for each academic community. If necessary,

organize subgroups within the community.

It is advisable to have leaders for each of the

research lines, although responsibility is

shared.

• Plan for innovation: set a schedule, activities,

and/or sponsorship for events. State tasks and

how to carry out research projects. Schedule

meetings to report progress and a calendar

of activities. Keep in mind participants’

affiliation since institutional policies may bias

work.

• Share findings: share progress and sustained

improvement. Impact is crucial at this stage.

As a consequence, on this stage an assessment

of its impact on its members´ professional

development and on students´ learning may

be reported. In fact research on how the cycle

is influencing participants may be done. Plan

an implementation time line.

• Disseminate: present results, provide

recommendations, act on data collected, and

publish. Find ways to influence policies.

• Redefine: reshape or refine the strategies.

Start a new inquiry based on identified results.

Involve new members in the community.

Following those six steps facilitates a working

plan for community members when planning the

operationalization of the PLC. It is important

for members to guarantee the cycle is followed in

such a way outcomes are achieved.

Conclusion

PLCs offer a magnificent chance for involvement

in professional development activities.

Professional development may be richer if

participants follow the model proposed in this

article which seeks to have an impact on the field

and on national policies. Table 3 summarizes the

operationalization of the PLC model proposed in

this article:

Professional development should be understood

as professional learning. Joint contributions

enrich and improve practices. Although there is

some evidence on how school PLCs operate and

some of their outcomes, there is still much to be

done in order to find out how university PLCs

function and their impact, especially in a country

such as Colombia where even national policies

advocate for their operation.

It is suggested that the model presented in this

article be implemented at many institutions in such a way that the desired impact is achieved and

further research can be done.

Notes

1

author´s translation

2

author´s translation

3

author´s translation

References

Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Stoll, L., Thomas, S., & Wallace,

M. (2005). Creating and sustaining effective

professional learning communities. General Teaching

Council for England. University of Bristol: England.

Caine, G., & Caine, R. N. (2000). The learning community

as a foundation for developing teacher leaders.

NASSP Bulletin, 84(616), 7-14.

DuFour, R. (2003). Building a professional learning

community: For system leaders, it means allowing

autonomy within defined parameters. The School

Administrator. Retrieved March 8, 2008, from http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0JSD/is_5_60/ai_101173944

DuFour, R. (2004). What is a professional learning

community? Educational Leadership, 61(8),6-11.

DuFour, R., Eaker, R., & Many, T. (2006). Learning by doing:

A handbook for professional learning communities

that work. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.

Eaker, R., & Gonzalez, D. (2006). Leading in professional

learning communities. National EakerForum of Educational Administration and Supervision Journal,

24(1), 6-13.

Feger, S., & Arruda, E. (2008). Professional learning communities: Key themes from the literature. Providence, RI: The Education Alliance, Brown University.

Haneda, M. (2006) Classrooms as communities of practice:

A reevaluation. TESOL QUARTERLY, 40 (4),807-817.

Harris, A. and Jones, M. (2010) Professional learning

communities and system Improvement.

Improving Schools, 13(2), 172–181. doi:

10.1177/1365480210376487

Henri R., & Pudelko B. (2003). Understanding and

analyzing activity and learning in Virtual

Communities. Journal of Computer Assisted

Learning, 19(4), 474-487.

Hord, S. (1997). Professional learning communities: What are they and why are they important? Austin, TX: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory (SEDL).

Hord, S., & Rutherford, W. L. (1998). Creating a

professional learning community: Cottonwood

Creek School. Issues about Change, 6(2), 1-8.

Huffman, J. B. (2000). One school’s experience as a

professional learning community. Planning and Changing, 31(1-2), 84-94.

Huffman, J. (2003). The role of shared values and vision in

creating professional learning communities. NASSP

Bulletin, 87, 21-34.

Huffman, J. B., & Hipp, K. K. (2003). Reculturing schools as professional learning communities. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Kline, M. (2007). Developing Conceptions of Teaching and

Learning Within Communities of Practice. US: University of Pensylvania.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate

peripheral participation. Cambridge, England:

Cambridge University Press.

Louis, K., & Kruse, D. (1995). Professionalism and

community: Perspectives on reforming urban schools.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Martínez, M. C. (2006) La Figura del Maestro Como

Sujeto Político. El Lugar de los Colectivos y Redes

Pedagógicas en su Agenciamiento. Revista Educere,

10(33), 243 – 250.