Introduction

The history of language teaching has witnessed an abundance of research into effective ways of teaching second or foreign languages. To offset the deficiencies of the traditional structural approaches, communicative language teaching (clt) has been introduced in English as a foreign language (efl) contexts to enhance learners' abilities to use English in real settings (Littlewood, 2007). Despite the increasing popularity of the communicative approach in western countries, many Asian countries have been unsuccessful in adopting clt principles in their English classes (Carless, 2003). While the majority of the teachers declare that they are applying a communicative approach, in practice they are following more traditional approaches (Karavas-Doukas, 1996). Since teachers play a determining role in the successful implementation of an approach, one of the reasons of the discrepancy between prescribed theory and teachers' actual classroom practice is rooted in neglecting teachers' attitudes and the effects their attitudes might have on their classroom behavior (Karavas-Doukas, 1996). In this regard, Wagner (1991) claims that if there are inconsistencies between the theories of an approach and teachers' beliefs, teachers will tend to interpret new information in light of their own theoretical attitudes in order to adjust them to their own teaching style. The other main factor in successfully implementing a new teaching approach into the English language classroom relies on learners' attitudes (Savignon, 1997), and as long as clt is considered a learner-centered approach, it would be both irresponsible and ironic to ignore learners' attitudes toward its tenets. Respecting the crucial role of the language learners in the learning process, Savignon (1997) believes that “if all the variables in L2 acquisition could be identified and the many intricate patterns of interaction between learner and learning context described ultimate success in learning to use a second language most likely would be seen to depend on the attitude of the learner” (p. 107). However, in discussions about clt and its learner-centeredness, the attitudes of learners are often neglected (Savignon & Wang, 2003). In spite of the warnings that learners’ perspectives on classroom pedagogy frequently differ from those of teachers (Mangubhai, Marland, Dashwood, & Son, 2005; Ngoc & Iwashita, 2012) and discrepancies between learners and teachers' attitudes can have a negative effect on the instructional results (Horwitz, 1988), there have been scant number of studies conducted in small-scale on teachers' or learners' perception concerning clt, let alone comparing these two.

In an attempt to let learners and teachers' voices be heard, the present study was designed to shed light on Iranian learners and teachers' attitudes toward six core clt elements: the importance of grammar; the use of group and pair work; the role and contribution of the learners; the role of the teachers in the classroom; the quality and quantity of error correction and assessment; and the role of the learners' native language in efl classes.

Review of Related Literature

Historical Background of Communicative Language Teaching

clt goes back to the end of 1960s when language teaching in Europe was looking for a change (Richards & Rodgers, 1986). Europe was undergoing social changes due to the economic and political interdependence of the countries within it, and the Council of Europe began to recognize the language needs of immigrants and guest workers. Due to the failure of traditional syllabi to facilitate learners’ ability to use language for communication, linguists strove to design a syllabus to attain the communicative goals of language teaching (Richards & Rodgers, 1986).

The first practical classroom application of clt can be found in the development of a notional-functional syllabus in the early 1970s. Different from the structural syllabus, Wilkins’s (1976) notional syllabus set function as one of the important elements of developing a foreign language curriculum. Instead of designing a syllabus based on the traditional concepts of grammar and vocabulary, Wilkins (1976) proposed one that considered two categorical types: notional categories and categories of communicative function. Wilkins first supported learners’ communicative needs by including the category of communication function in a notional syllabus, and had a significant impact on the development of clt. The Council of Europe even developed its own communication language syllabus based on Wilkins’s notional syllabus; it consisted of situations, language activities, language functions, notions, and language form.

Grounded on a strong theoretical basis, the communicative approach was widely accepted by British language teaching professionals, curriculum planners, textbook writers, and even the government. It has been quickly adopted and expanded in the world of second and foreign language teaching with the goal of developing learners’ communicative competence (Richards & Rodgers, 1986).

Teacher and Learner Attitudes

Because it is open-ended, teachers have interpreted the clt approach in a multitude of ways (Anani Sarab, Monfared, & Safarzadeh, 2016). Whatever approach teachers follow in their real teaching environment, their instructional decisions are supposed to be determined by their beliefs about teaching (Phipps & Borg, 2009). Accordingly, taking teachers' beliefs into consideration is requisite for and critical to the successful implementation of innovative programs and effective education (Richardson, Anders, Tidwell, & Lloyd, 1991).

Reviewing the existent literature reveals that there have been many studies on investigating teachers' beliefs and attitudes in the context of English language teaching (elt) in recent years, suggesting the importance of this issue in esl and efl (e.g., Asgari, 2015; Gorsuch, 2000; Nishino, 2008; Taguchi, 2015; Ashoori Tootkaboni, 2019; Ashoori Tootkaboni & Khatib, 2017). However, research on their beliefs and attitudes about clt remains quite limited.

Studies comparing the attitudes of teachers and learners show that in most cases their beliefs do not conform (see for example, Jarvis & Atsilarat, 2004; Matsuura, Chiba, & Hilderbrandt, 2001; Ngoc & Iwashita, 2012; Nunan, 1988; Schulz, 1996).

In a study, Nunan (1988) asked 60 Australian teachers and 517 learners to rate ten learning activities based on their usefulness. The outcomes showed that they rated only one out of ten activities the same as each other. Schulz (1996) also compared post-secondary foreign language learners and teachers in the United States to find out their attitudes about the effectiveness of explicit grammar teaching. The findings revealed that there were some disagreements between learners and teachers' attitudes regarding the role of explicit grammar teaching in general and error correction in particular. While learners were generally in favor of explicit focus on form and error correction, their teachers had a wider variety of opinions on them.

Matsuura et al. (2001) compared the beliefs of university teachers and students in relation to the learning and teaching of communicative English in Japan. More than 300 students and 82 college teachers were asked to fill out a questionnaire to assess their attitudes toward issues such as the following: important instructional areas, goals and objectives, instructional styles and methods, teaching materials, and cultural matters. The results showed that learners preferred traditional and teacher-centered elt approaches. On the other hand, teachers were more interested in recent pedagogical shifts such as learner-centered approaches, integration of all four language skills, and more focus on fluency.

In Taiwan, Jarvis and Atsilarat (2004) explored Thai teachers and students' perception of clt in order to determine whether it was a suitable approach for that country’s context or not. The results revealed that although teachers understood clt, they encountered problems in its implementation. Moreover, students favored learning styles that were thoroughly incompatible with clt. In another study, Ngoc and Iwashita (2012) compared Vietnamese university teachers and learners' attitudes toward four factors in the clt approach: the teacher’s role, grammar instruction, error correction, and group and pair work. To this end, a questionnaire was administered to 88 pre-intermediate to intermediate language learners and 37 teachers. The result revealed that although both groups held positive attitudes toward clt, teacher participants had more favorable views than learners for all the aspects except group and pair work, suggesting that in order to implement clt successfully, it is necessary to consult learners in advance and establish a link between teachers and learners' preferences.

In the efl context of Iran, although clt has been welcomed by syllabus designers and material developers, there have been very few studies conducted on teachers' beliefs toward the communicative approach. Additionally, given the importance and central role of learners in language education and despite the warnings that discrepancies between learners and teachers' beliefs can have a negative effect on instructional results (Horwitz, 1988), Iranian efl learners' beliefs toward clt have not sufficiently been addressed. Consequently, there is a dire need to delve into the beliefs of both learners and teachers regarding adjusting the clt approach to Iran’s efl setting.

Research Questions

Since teaching for communicative competence appears to be the appropriate guiding principle of English pedagogy in settings such as Iran, where learners and society as a whole respect and value communicative skills (Maftoon, 2002), the present study attempts to address the lack of attention to it and investigate the extent to which clt and its main principles are welcomed by Iranian efl teachers and learners. For the purpose of the study, the following research questions were posed:

-

What is the overall attitude of the Iranian efl teachers with respect to clt principles?

-

What is the overall attitude of the Iranian efl learners with respect to clt principles?

-

Are there any significant differences among Iranian efl teachers and learners in terms of their attitudes toward clt principles?

Method

Participants

There were 396 participants in total, made up of 154 English language teachers and 242 English language learners who were selected on the basis of their availability in private English language institutes in the two provinces of Mazandaran and Tehran in Iran. Table 1 provides the general profile of the participants.

Instruments

A questionnaire addressing six core principles of the clt approach, namely, the role of the learner, the role of the teacher, group/pair work, the place and importance of grammar, the role of the learner’s native language, and the quality and quantity of error correction and assessment was developed and evaluated to serve as the main instrument of the study. The final version of the questionnaire consisted of 28 statements, including 21 favorable and 7 unfavorable statements which followed the Likert technique of scale construction.

Questionnaire Validity and Reliability

After generating the items, a panel of experts in applied linguistics were asked to check the items in terms of validity, content representativeness, ambiguity, and appropriateness. Based on the feedback obtained, several items were modified for clarity of expression. Afterwards, the questionnaire was piloted with 300 English language learners similar to the target population. After collecting the data, the researcher calculated validity coefficients using both exploratory factor analysis (efa) and confirmatory factor analysis (cfa). For more information on the indices of the six factors in terms of efa and cfa, see Appendices A and B, respectively.

Regarding the questionnaire’s reliability, the internal consistency reliability estimate for the Likert-scale questions using Cronbach’s alpha was estimated to be .77, which is more than the acceptable measure of reliability coefficient of .6 recommended by Dörnyei (2010).

Data Analysis

To see what beliefs Iranian efl teachers and learners hold about clt principles, the data gathered through the questionnaire were analyzed using the following procedures.

The data collected through the questionnaire were subjected to descriptive statistics utilizing the mean, frequency, and percentage of each statement. The scale ranged from 6 to 1, with 6 being “strongly agree” and 1 indicating “strongly disagree.” Since the questionnaire consisted of favorable and unfavorable statements, the scale’s pattern for the coding of the data depended on which one each statement was. For the positive statements, the participants’ responses were coded as strongly agree = 6, somewhat agree = 5, agree = 4, somewhat disagree = 3, disagree = 2, and strongly disagree = 1. For the negative statements, the point values were reversed. Thus, the higher the mean value, the more positive the attitude toward clt. In order to present a clearer picture of the participants' attitudes toward clt principles, their responses to the six main clt domains were weighted and classified into three categories: favorable, rather favorable and unfavorable. The favorable principles ranged from 4.34 to 6, the rather favorable principles ranged from 2.67 to 4.33, and the unfavorable ones ranged from 1 to 2.66. Moreover, to see whether there was a significant difference between efl teachers and learners and where the differences lay, an independent-samples t test was run separately for each principle.

Results and Discussion

What is the overall attitude of the Iranian efl teachers with respect to clt principles?

To answer the first research question, the teachers' responses were analyzed through SPSS V23. Table 2 shows the results of the weighting of the clt principles and the descriptive statistics for the teacher participants’ attitudes.

As demonstrated in Table 2, except for the role of the grammar (M = 4.24) which was evaluated as rather favorable, teachers held favorable attitudes toward all principals, i.e., learners' role (M = 4.82), teacher's role (M = 5.06), error correction/evaluation (M = 4.46), group/pair work (M = 4.49), and the role of the student’s native language (M = 4.78). Teachers' rather favorable responses in terms of the role and importance of grammar reveal that they appreciate both traditional and communicative methods for teaching grammar. For more information, see the teacher participants' responses to the clt questionnaire in Appendix C.

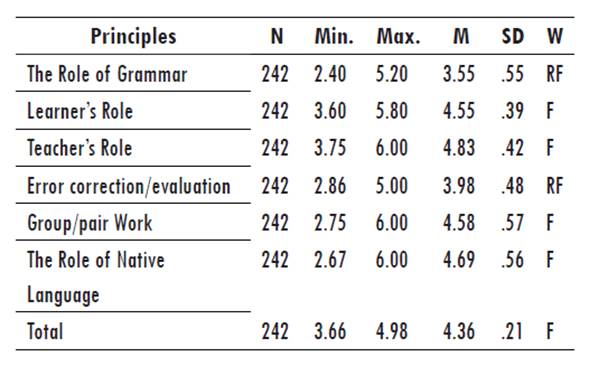

What is the overall attitude of the Iranian efl learners with respect to clt principles?

As Table 2 does for the teachers, Table 3 presents the results of the descriptive statistics and weighting of efl learners' attitudes toward the six core tenets of the clt approach. In line with the language teachers, the efl learners also appreciated the principles pertaining to the teacher's role (M = 4.83), the learners' role (M = 4.55), the role of group and pair work (M = 4.58) and the role of their native language in efl classes (M = 4.69). However, their responses to the role of grammar (M = 3.55) and error correction/evaluation (M = 3.98) were evaluated as rather favorable. For more information, see the learner participants' responses to the clt questionnaire in Appendix D.

Are there any significant differences among Iranian efl teachers and learners in terms of their attitudes toward clt principles?

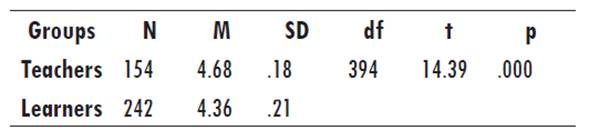

To learn about the significance of the differences between the efl teachers and learners, an independent-samples t test was run. The results are presented in Table 4.

From the results presented in Table 4, a significant difference can be interpreted between the efl learners and teachers concerning their attitudes toward clt’s main principles, t (14.39), p = .000 < .05. To find out where the differences were, an independent-samples t test was run separately for each principle. The results are presented in Table 5.

As can be seen, the difference between Iranian efl teachers and learners is significant in terms of the roles of grammar, learners, teachers, and error correction/evaluation. However, there are no significant differences between language learners and teachers concerning group/pair work and native language role.

The first attitudinal gap between the two groups of participants concerns the importance of grammar instruction in the foreign language education environment. The difference between the teacher participants’ attitudes (M = 4.24) and the learner participants’ attitudes (M = 3.55) was significant (t = 9.56, p = .000 < .05). Data analysis suggests that while teachers’ attitudes were more in line with the clt principles of grammar instruction, those of the learners indicated a preference for aspects of traditional methodology, including not presenting grammatical rules within a communicative context (item 15) and rejecting the idea that less attention should be paid to the overt presentation and discussion of grammatical rules (item 14). As can be interpreted from the results, learners were influenced by the deeply rooted belief in the importance of learning the structural aspects of language as a foundation of language learning.

Secondly, the two groups had different attitudes toward the role and contribution of learners in efl classes. The teachers’ attitudes (M = 4.82) were significantly more positive than the learners’ attitudes (M = 4.55), where t = 6.69, p = .000 < .05. While 64.9% of the teacher participants expressed disagreement with the idea that "the learner is not in a position to suggest what the content of the lesson should be or what activities are useful for him/her" (item 5), 74.4% of the learner participants agreed with it.

The third mismatch between teacher and learner attitudes concerned the role of the teachers in the classroom. The teachers’ attitudes (M = 5.06) were significantly different from those of the learners (M = 4.83), where t = 4.16, p = .000 < .05. While for most learners it was the teachers’ role to act as an authority, most teachers thought it was more important to facilitate communication among learners and motivate them in any way to work with language. The finding is consistent with Ngoc and Iwashita's (2012) claim that efl teachers were expected to be the fount of knowledge and have the role of authority.

The fourth inconsistency between efl learners and teachers deals with the ways in which errors should be treated and evaluation should be carried out in foreign language classrooms. Once again, the teacher participants' attitudes (M = 4.46) were more significantly in line with clt principles than the learners' attitudes (M = 3.98), where t = 16.05, p = .000 < .05. Concerning error correction, teachers' attitudes tended to be in line with Larsen-Freeman (2000) and Richards's (2006) claim that as far as errors do not impede communication and comprehension, they should be treated as natural in the learning process. Regarding the focus of assessment, while the majority of learners (55.7%) thought that their performance should be judged based on their vocabulary and structural knowledge, most of their teachers (93.5%) did not share that view (item 6). These findings are in line with Lewis and McCook’s (2002) claim that verbal perfection has traditionally been valued across many Asian cultures. On the other hand, the results oppose the findings of studies conducted in other contexts (e.g., Horwitz, 1988; Kern, 1995) in which the majority of language learners expressed a desire for constant error correction.

The two factors that did not reveal a significant difference between teachers and students' attitudes were the use of learners' native language in efl classes (items 22, 23, and 24) and employing group and pair work (items 25, 26, 27, and 28). In regard to using learners' mother tongue in language classes, both groups of participants held a strong conviction that the learner’s native language should not be used as a main vehicle of communication in the language classroom (tm = 5.68, lm = 5.52, item 23). Both groups also demonstrated agreement that judicious use of a learner’s native language is acceptable when feasible (item 22). Concerning group and pair work activities, since there was only a slight difference between the two groups’ average scores (tm = 4.78, lm = 4.69), the results indicate that both had favorable attitudes toward these communicative activities, indicating that learners may see cooperating with their classmates as an effective means of acquiring knowledge and prefer it to working on their own. These findings seem to contrast sharply with those of Sullivan (1996), who argued that communication in the classroom is much easier for learners in traditional whole class settings rather than in small group ones. On the other hand, the findings seem to be in accordance with Nguyen (2002), who believed learners are no longer thoroughly passive but actually enjoy taking part in activities that assist them in using the language. They may also express that learner preferences seem to be gradually moving from the perceived comfort of traditional whole-class setting activities toward group and pair work activities (e.g., Huynh, 2006).

Conclusion and Implications

Since understanding teachers and learners’ attitudes is quite crucial for effective implementation of any innovative language education approach or method, the present study was designed to delve into Iranian efl teachers and learners' beliefs toward six core tenets of clt.

The obtained results showed that both groups of participants held favorable attitudes toward clt principles. This is a positive indication for those interested in the implementation of clt in the context of Iran because it reveals that the main clt tenets, which largely revolve around learner-centeredness, have a good level of acceptance in this context. Gaps, nonetheless, do exist between teachers and learners’ attitudes toward the importance of grammar, error correction/evaluation, and whether the learner or the language teacher should have the main role in efl classes, with learners retaining more positive attitudes toward traditional classroom teaching aspects.

The findings of this study have a range of implications and would likely be most beneficial to three constituents of English language education: efl teachers, reform agents, and efl teacher education programs.

Implications for efl Teachers and Learners

Under the premise that there is a mutual relationship between beliefs and behavior it behooves teachers and learners to reflect upon their beliefs about English language education and their teaching and learning experiences to see whether or not there are any gaps, mismatches, or self-justifications between their real experience and the relevant underlying theories of language teaching and learning. In addition, teachers need to carefully inspect whether they stick to their beliefs merely because their attitudes are not in harmony with the demands of the reforms. Furthermore, they need to examine whether their negative attitudes toward certain reform policies are due to their desire to cling to the status quo which they may consider as the ones threatened by the policies and reform agents.

Implications for Change Agents

Change agents in education must accept that simply developing and manipulating reform policies is not enough to ensure that the policies will be applied by efl teachers in their classroom teaching. Since teachers are living the realities of educational sites and know the ins and outs of existing constraints, reform agents must realize that teachers are the ones who are at the center of English language education and therefore determine the success of any kind of reform. Accordingly, any reform attempt that does not take teachers' attitudes into consideration will likely fail.

Implications for efl Teacher Education Programs and Specialists

efl teacher education programs, particularly those for in-service teachers, should acquaint teachers with the practice of reflection, helping them to reflect not only on the theoretical and methodological aspects of their teaching practices but also on the consequences of their own beliefs, perceptions, and resulting teaching practices (Yook, 2010). In other words, by providing reflection opportunities for efl teachers, teacher education programs can help them to view their beliefs and practices critically and reflectively to find the gaps between them, making them better able to close such gaps whenever possible.