Introduction

Greg Peters, chief product officer at Netflix, claims that one of the largest current challenges for this platform concerning US audiences is to make dubbing accepted in the mainstream for the first time (Bylykbashi, 2019) in its attempt to encourage American customers to watch foreign language productions. However, there was a period in the 1960s and 70s when dubbed English versions of Euro-Westerns and Martial Arts films (Hayes, 2021) were released in mainstream cinemas in the US and other English-speaking countries, unlike most other foreign language productions which were subtitled and released in the more restricted art-house cinema circuit. There is, then, a precedent that can contribute to understanding the effect that this unusual linguistic transfer practice had on target texts in English when compared to original American productions, whose research results could be transferred to the analysis of contemporary productions dubbed into English.

This article focuses on the former genre and, more specifically, on Euro-Westerns with Spanish screenwriters in order to analyze whether their translation into English for dubbing had any linguistic effect on the canonical lexis of the genre established by original American Westerns.

Dubbese, a term coined by Myers (1973), is foregrounded by Gómez Capuz (2001) as a major influence in Spain concerning the outstanding presence of calques derived from the translation of English language films into Spanish for dubbing. Defined by Marzá and Chaume (2009, p. 36) as “a culture-specific linguistic and stylistic model for dubbed texts,” dubbese refers to the resulting lexis of a translation routine based mainly on calques and lexical loan translations, which initially sounded contrived when compared to the normative usage of the target language but eventually became canonical and, therefore, the norm (Toury, 1978) within the context of viewing of an overwhelming number of dubbed American films released in Spain.

The influence of the subsequent canonical lexis was such that it would eventually become a requirement for acceptability within the Spanish audiovisual polysystem, considering Toury’s (2012, p. 94) reminder of these “cases where the text’s acceptability as a translation and the conditions underlying it do not fully concur with its acceptability as a TL [target-language] text in general; that is, when the norms governing translations differ from those that govern non-translations.” Within the specific film genre analyzed in this article, the Western, linguistic expectations would be triggered more easily for Spanish audiences due to its powerful iconographic code (Chaume, 2004), which contributed to visually identifying its specificity and, therefore, to accepting and even requiring the use of a lexis that differed from the one used in everyday life.

In the 1960s, a sub-genre was derived from American Westerns in Spain and other European countries-Euro-Westerns-which, in many cases, had their original script written in Spanish for films shot mainly in Spain. With the formation of a comparable corpus made up of the versions dubbed into Spanish of a sample corpus of fifteen American Westerns and another sample corpus of fifteen original Spanish scripts of Euro-Westerns, this article reports research carried out to establish whether local scriptwriters made use of normative Spanish language in their creative work or the dominant artificial dubbese of the time.

The final twist is that many Euro-Westerns were exported to English-speaking countries, where they were unusually dubbed into English rather than subtitled, as most other foreign films were. This may have been because, bearing in mind that their plots were technically set on American soil with English-speaking characters, it would have created an incongruity for target culture audiences if the dialogues were uttered in Spanish or Italian, the other language in which many source texts were written. The derogatory term (Frindlund, 2006; McDonald Carolan, 2020) Spaghetti Westerns was then generated to refer to the country which produced or co-produced them, foregrounding their non-American origin and their excessive violence, which prevented this sub-genre from reaching art-houses, where more respectable foreign films subtitled into English were shown.

Consequently, the main aim of this article is to analyze by means of another comparable corpus, made up of fifteen original American Western scripts and fifteen versions dubbed into English of Euro-Westerns, whether the translation into English of the latter allowed the Spanish dubbese to pervade the established standard language of the original American genre. To do that, it evaluates the effect made by a stranger, the Spanish scriptwriter, who entered the saloon, the cultural context where the genre originally came from, in the 1960s and 70s.

There has been plenty of scholarship on dubbese concerning Spain and Italy, countries which experienced this phenomenon in their translation for dubbing of English-speaking audiovisual productions. Afro-dubbese (Naranjo, 2015), when referring to translation into Spanish of African American cinema, or doppiaggiese (Schwarze, 2012), to allude to the linguistic interference of the English language in the translation for dubbing into Italian, are some of the terms used in these analyses. In the research concerning other languages, this issue has been explained without coining a specific term, as in the studies of this effect in the translation for the dubbing of American productions into German (Queen, 2004) or French (Caron, 2003). However, there is a research gap in translation studies for English-dubbed versions for two obvious reasons: the established translation mode for foreign audiovisual productions in English-speaking countries has generally been subtitling, and these countries’ commercial audiovisual needs had been fulfilled thus far by productions in their own language, mainly from US origin, so there was no requirement for the analysis of a translation practice that was hardly present.

But now there is an attempt in English-speaking countries to dub a wide variety of foreign language productions, mainly for video-on-demand platforms. Therefore, the analysis of the effect of translations for dubbing into English of those 1960s and 70s Euro-Westerns upon the canonical lexis of the original genre in the target language could be applied to current dubbing translations promoted by major platforms to verify whether an English dubbese may be developing, proving to be a field of study whose conclusions could be useful for both researchers and translators of dubbed English versions.

Theoretical Framework

The concept of polysystem (Even-Zohar, 1990) applies to the dynamic relationship that a cultural system establishes between its source and translated texts incorporated in their culture. This is a starting point to contrast the theoretically differing approach to dubbed Westerns in the Spanish and American cultural contexts. In the former, they were given a dominant position since they were far more popular than any Spanish film production, whereas in the latter, they were incorporated secondarily because, at least technically, they were following the normative usage of the target language.

In the case of dubbed versions in Spain, a conceptualization developed by Venuti (1995, p 20) has to be taken into account: “Foreignizing translation signifies the difference of the foreign text, yet only by disrupting the cultural codes that prevail in the target language.” On the other hand, dubbed Euro-Westerns in English-speaking countries technically had to fit into the canonical lexis established by American Westerns. Therefore, the norm (Toury, 1978) in the Spanish cultural context was to adjust to the development of its artificially created dubbese, whereas in English- speaking countries, dubbed versions of Euro-Westerns were expected to follow norms of usage of the target language. However, as we shall see, the latter did not always conform to the norm.

The principle of relevance developed by Sperber and Wilson (1995), a theory of communication focused on the contextual effects perceived on the cognitive processing effort, which was later applied to translation by Gutt (2000), generates some useful concepts that can be applied specifically to the analysis of the translation of “mainstream film, a form of communication that automatically draws attention to the relevance of its cues” (Vandaele, 2019, p. 230). One concept is ostensive communication, which describes the specificity of a message’s typology. This could relate to the distinctive multimodal narrative of American Westerns in the source context, which Spanish translators might have tried to emulate by developing an equally outstanding lexis which moved away from the norms of usage of the target language.

Another applicable concept developed by Sperber and Wilson would be cognitive environment, which, in the case of such a visually identifiable genre, would generate linguistic expectations for dubbed American Westerns in Spain restricted to an intertextual relationship held by the average spectator with previously viewed dubbed films; this would result in a linguistically secluded glossary with hardly any connection with the audience’s everyday language. In the case of English-speaking viewers of dubbed Euro-Westerns, since this sub-genre was commercialized as if it were the original genre, the expectations would be that the lexis used was identical to the one found in canonical American Westerns. Therefore, in both cultural contexts, a distinctive lexis stored in the memory of spectators would likely make them anticipate the reception of a canonical terminology related to Westerns which would become a requirement of acceptability in the target polysystems.

Method

By means of the software SketchEngine (Kilgarriff et al., 2004), a sample parallel corpus of fifteen American Westerns released in Spain between the 1940s and the 60s was developed. These samples are made up of their original scripts in English and their translation for dubbing into Spanish. This enables keywords of the genre from the original source texts to be input, and the system displays all the lines of dialogue that include them (Figure 1). Another parallel corpus of fifteen Euro-Westerns of the 1960s and 70s with their Spanish scripts and their versions dubbed into English was developed similarly. This alignment structure enables the identification of translation pairs, and the statistical results contribute towards reaching conclusions on the hypothetical problems.

The above-mentioned parallel corpora also make it possible to establish a comparable Spanish corpus of dubbed versions of American Westerns and the original Euro-Western scripts to analyze whether the latter’s scriptwriters made use of the artificial Spanish dubbese or followed their language’s normative use. Finally, and more importantly, another comparable corpus formed by original American Westerns and dubbed into English Euro-Westerns elucidates how the translation of the latter might have had an effect on the English linguistic canon of the original genre.

Corpora

A compilation of fifteen American Westerns whose Spanish-dubbed versions into were released in Spain during the 1940s (the period when the first dubbed versions of American Westerns can currently be identified) and the 1960s (the decade when the Euro-Western surged) has been put together to make up a parallel corpus that can contribute to determine how a distinctive lexis related to the genre was developed in Spain (see Table 1). These films have been chosen according to the presence of specific words in the source texts which can be considered distinctive of the genre or, at least, whose translation for dubbing into Spanish made them part of the canonical lexis in the target context. Since the effect of the translation would take place in the context of reception, the films are listed in the chronological order of their commercial release in Spain, which is relevant to the analysis of the diachronic formation of this lexis.

Table 1

Parallel Corpus of American Westerns and Their Dubbed Versions Released in Spain.

A compilation of fifteen Euro-Westerns was also put together, representing this short-lived sub-genre whose popularity ran for hardly a decade (Table 2). The main criterion for their selection was that they had a Spanish scriptwriter (whose name is included in the listing) and that they were dubbed into English. In addition to this, the fact that they have distinctive terminology related to the genre connected to sub-topics developed by the analysis of the translation for dubbing into Spanish of the previous compilation of American Westerns has also been relevant. Whenever possible, the year of the premiere of the dubbed version into English has been included.

Table 2

Parallel Corpus of Euro-Westerns with a Spanish Scriptwriter and Their Dubbed Versions Released in English-Speaking Countries

The anglicization of the names of Spanish and Italian professionals would prove that the initial intention was to aim at domestication (Venuti, 1995); commercially speaking, it was an attempt to sell these Euro-Westerns abroad (as well as locally) as American productions. For instance, the Spanish director and scriptwriter of the first film of the corpus, Ricardo Blasco, had his name changed to Richard Blasco, and the one of the second film, José Luis Borau, had the final letter of his surname replaced with a w, which is non-normative in Spanish, in a hypothetical attempt to anglicize it. It must also be remembered that the Italian director of the third film of the corpus, Por un puñado de dólares (1965, A Fistful of Dollars), canonical in the history of Euro-Westerns, Sergio Leone, had his name changed to Bob Robertson for the international release of the film. Spanish and Italian actors of the genre followed suit: Antonio Luiz de Teffe/Anthony Steffen; Francisco Braña/Frank Braña; Alfredo Sánchez Brell/Aldo Sambrell, and many more.

American actors were also lured into these profitable Euro-Westerns in order to make the production look as much as possible as the original genre. In the final film of the corpus, En el Oeste se puede hacer…amigo (1973, It Can Be Done… Amigo), we can find, for instance, a well-known American actor, Jack Palance, sharing the cast with Bud Spencer (born Carlo Pedersoli), who had famously changed his name to honor his favorite American beer and actor (Sanderson, 2015), and consecrated Spanish actor Francisc o Rabal (by then he had worked with distinguished European directors such as Michelangelo Antonioni, Claude Chabrol, and Luchino Visconti), who, having a Spanish name, was thus removed from most advertising of the film in Spain (Figure 2).

American Westerns and their Translation for Dubbing into Spanish

According to Newman (1990, p. 46), “Stagecoach was the most important of several 1939 movies (Jesse James, Dodge City, Union Pacific, Destry Rides Again) that revitalized the talking Western after a decade of ‘B’ and series quickies.” Due to warfare issues, it was released in Spain five years later with a very positive reception in the target context; it is included as the first film of the corpus because it is the oldest dubbing into Spanish of a Western which has been identified. It therefore becomes a starting point to analyze the evolution of the translation for the dubbing of specific lexical elements which would become distinctive of the genre. The six terms in Table 3 can be found repeatedly in different sections of the film.

Table 3

Terms Found in Stagecoach

Whisky and sheriff were already part of the Spanish linguistic landscape before the advent of sound on film, or of film itself; they can be found, respectively, in the Spanish novels Pequeñeces (Coloma, 1891) and Aita Tettauen (Pérez Galdós, 1905).

The rest of the Spanish terms foregrounded in the table are what would be considered formal equivalents of the source text lexical elements. For instance, the other figure of authority mentioned, marshal, a federal law enforcer, was suitably translated as comisario, an equivalent national figure of authority in Spain. As for weapons, shotgun, “a long gun that fires a large number of small metal bullets at one time, designed for shooting birds and animals” (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.) finds its correspondence in the commonly used escopeta in the target context. And when the hypernym “gun” refers to a short firearm, its customary equivalent translation would be pistola, which shares an etymological origin with “pistol.” Finally, “reverend,” a neutral term to refer to members of the clergy of any Christian creed, had an almost identical term in Spanish, reverendo, due to its Latin etymology even though it is a non-normative term in Spanish (sacerdote or cura are the common terms to refer to churchmen). In any case, the concept of formal correspondence established by Catford (1965, p. 27) as “any TL category which may be said to occupy, as nearly as possible, the ‘same’ place in the ‘economy’ of the TL as the given SL [source-language] category occupies in the SL” is present in these examples emphasized in the first film of the corpus.

However, three normative terms mentioned in the previous paragraph, comisario, escopeta, and pistola, practically disappeared as translations of, “marshal,” “shotgun,” and “gun,” respectively. In the 75 occurrences of “marshal” which can be found in the following five films of the corpus, from My Darling Clementine (1946, Pasión de los fuertes) to 3.10 Train to Yuma (1957, El tren de las 3.10), it was always translated as sheriff. This leads to the remarkable finding that this Anglicism is more present in the corpus of Spanish dubbed versions than in the original fifteen American Westerns (other terms such as “lawman” and “deputy” were occasionally translated as sheriff as well) in spite of the fact that, technically, this direct active Anglicism incorporates a phonetic borrowing, the fricative postalveolar consonant /ʃ/, which is non-existent in the Spanish language and, therefore, not included in the norms of usage of pronunciation. In two of the following dubbed American Westerns, The Left-Handed Gun (1958, El zurdo) and The Man who Shot Liberty Valance (1962, El hombre que mató a Liberty Valance), there was a short-lived return to the normative comisario as a translation for “marshal” before it definitely disappeared from the rest of the corpus.

As for the hypernym “gun,” it was eventually translated with two anglicisms: revólver (with a stress on the o to differentiate it from the verb revolver, which means to stir or turn around in Spanish) when it referred to a handgun, and rifle (spelled the same in Spanish and English but used in Spanish here) when it referred to a long gun. In the latter case, even when the term used in the source text was “shotgun,” the term mainly used to translate it was rifle, as can be found in Rio Bravo (1959, Río Bravo) and The Left- Handed Gun, even though it referred to a different type of firearm. In 3.10 Train to Yuma, it was even translated as carabina (carbine), yet another kind of firearm, which also seemed to be acceptable, as long as escopeta, perceived as too local, could be avoided. As for revólver, seventeen occurrences are recorded in the corpus of dubbed versions whereas “revolver” does not appear a single time in the corresponding American source texts.

Therefore, the formal correspondence observed in the first dubbed film of the corpus seemed to have decreased in the following films in favor of a foreignizing tendency in the development of a distinctive lexis for this specific genre, mainly with the use of Anglicisms which were progressively accepted as linguistic items in the target language. Apart from the adoption of Anglicisms, there were other strategies of linguistic transfer applied, such as loan shifts or lexical loan translations, which contributed to differentiating the canonical language used in this film genre from normative speech to a greater extent (Sanderson, 2021).

For instance, the first time “saloon,” “A public bar, especially in the past in the western US” (Cambridge Dictionary, n. d.) appears in the corpus, in My Darling Clementine, it is translated as salón, when the word already existed in Spanish to refer to “living room” or “lounge.”

This unnecessary loan shift (there is a wide variety of terms in the Spanish drinking culture that could have been used) is yet another example of a seeming attempt to develop a specific lexis for the distinctive multimodal narrative of Westerns which moved away from the norms of usage of the Spanish language. In the dubbed versions that came after this film we can find a variety of options to translate “saloon,” led by the above mentioned salón (53 per cent), followed by the lexical borrowing bar (33 per cent), which had entered the normative Spanish language through journalism (Stone, 1957), and, exceptionally, the more normative taberna (tavern) in 3.10 Train to Yuma, and cantina (canteen), alternating with salón, in The Man who Shot Liberty Valance.

In the last two films of the corpus of American Westerns dubbed into Spanish we can find a case of lexical loan translation, which is “the morphemic substitution of a polymorphemic unity of a foreign language by means of elements, previously existing in the receiving language as independent lexemes, but new as a lexical compound” (Gómez Capuz, 1997, p. 88). In this case, the strict censorship imposed by Franco’s dictatorship must be acknowledged (Gutiérrez Lanza, 2000), since it exerted a huge influence in any creative work, including translation. Westerns were, by and large, a conservative and chauvinistic genre, and the American film industry already imposed its own restrictions by means of the Production Code Administration and the Catholic Legion of Decency (Camus-Camus, 2015). However, the repeated appearance of taboo language once the Motion Picture Association of America modified its rating system in 1968 (Jowett, 1990) seems to have put Spanish translators in a difficult position. The expletive “son of a bitch,” used five times in The Wild Bunch, was translated into Spanish as “hijo de perra,” a lexical loan translation of the original, with an atypical reference to the animal.

The customary hijo de puta can be traced back to respectable literary works such as Cervantes’ El ingenioso caballero Don Quijote de la Mancha (2015), which expresses, “no es deshonra llamar hijo de puta a nadie cuando cae debajo del entendimiento de alabarle” (p. 134). As can be verified in CORDE (Corpus Diacrónico del Español, n. d.), a database from the RAE (Real Academia Española), hijo de puta is found in various Spanish texts since the fifteenth century even though it is taboo language. Therefore, this lexical loan translation was technically unnecessary; but as swearing was banned under Franco’s dictatorship, it was eventually adopted in the local dubbese (according to the database above-mentioned, hijo de perra can only be found once in print in Spain [a translation] prior to its use in dubbese) to the extent that, decades after Franco’s death and the subsequent abolition of censorship, it had become so standardized in this genre that it can still be found in the dubbed version of, for instance, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007, El asesinato de Jesse James por el cobarde Robert Ford).

In the previous film of the corpus, Bandolero!, the expletive was only used once in the source text, and it was translated with an equally anomalous hijo de un puerco (son of a pork). However, the most remarkable issue in this film is that its original title in the USA was a single word in normative Spanish, the archaism Bandolero! (bandit), which had never been used in the previous thirteen dubbed westerns, where the customary term to translate “outlaw” or “bandit” was another archaism: forajido. Bandolero! was released in Spain with exactly the same title as the original (Figure 3), even though it implied making a punctuation mistake in Spanish, since, in the target language, exclamation marks are placed at the beginning and at the end of the word or sentence. It was eventually modified in another Spanish poster that advertised the film (Figure 4), but it stands as an example of the dominant linguistic effect of the source culture, in this case even with a normative Spanish word, simply because it had been used in the source text. The three times “bandolero” is uttered in the original English version were duly translated as such although it statistically contravened the canonical dubbese. It is worth noting, however, that the use of the customary term forajido was not always properly dealt with in the target context. The Spanish release of the Euro-Western La grande notte di Ringo (Mario Maffei, 1966, Ringo’s Big Night), not included in the corpus because its sole scriptwriter was its also Italian director, was premiered in Spain as Trampa para un foragido (Figure 5) with a misspelling in the canonical term used.

On the whole, the outstanding iconographic code referred to by Chaume (2004) concerning this genre may have encouraged a generalized attempt by Spanish audiovisual translators to provide an equally outstanding lexis which, in the target language, diverged from the norms of usage. There was a distinct asymmetry between source and target cultures; but there were also several shared features, such as “marshal” (comisario) or “shotgun” (escopeta), whose formal Spanish equivalents eventually disappeared in the artificially created dubbese. In these and other cases, the lexical need foregrounded by Weinreich (1968) as a motivation for the incorporation of foreign words in the target language was not an issue, since there were plenty of pre-existent corresponding equivalents, as can be found in the first dubbed film of the corpus; but they were subsequently erased from most target texts that came after it. According to Rabadán (1991) in her research on translation from English into Spanish, equivalence in translation depends on the socio-cultural circumstances of the polysystem in which the translator works. In the case of Spain, according to the examples which have been analyzed in this section, translation for dubbing into Spanish of American Westerns was subsidiary to the source cultural context, even if it was detrimental to semantics (as with rifle or salón), which, as Rabadán foregrounds (39), is one of the basic foundations of any translemic model which follows Catford’s theorization of equivalence. How these circumstances would affect Spanish scriptwriters of Euro-Westerns is another matter that will now be approached.

Euro-Westerns and Their Translation for Dubbing Into English

The research in this section of the article is initially focused on whether Spanish scriptwriters of Euro-Westerns in the 1960s and 70s were influenced by the artificial dubbese developed in the local audiovisual translations analyzed above. But the main purpose of the whole article is to verify if the decisions of these scriptwriters had an effect on the translation for the dubbing of Euro-Westerns into English, the language in which the original genre had been created.

Using the words foregrounded in the opening examples of the previous chapter as a starting point, we can only find one occurrence of escopeta in the whole corpus of fifteen Euro-Westerns (in Brandy; 1964, Ride and Kill); and comisario does not appear a single time, which would confirm the tendency to erase words which sound too normative. Actually, marshal was coined as a Spanish word by local scriptwriters even though, as sheriff (present in most Euro-Western scripts), it also contains the fricative postalveolar consonant /ʃ/, a phonetic borrowing non-existent in the Spanish language. In Arizona vuelve (1971, Arizona Colt Returns), for instance, its scriptwriter, Joaquín Luis Romero Marchent, incorporates the term marshal five times in the source text. This was yet another direct Anglicism brought into the Spanish language which, for obvious reasons, did not have an effect on the translation for dubbing into English.

This would be an example of Spanish scriptwriters definitely favoring Anglicisms to the extent of going beyond the generalized strategy which has been observed above in the work of local translators. Remarkably, marshal was eventually incorporated as part of the canonical lexis in Spanish dubbing translations themselves. We can find examples in True Grit (Ethan Coen & Joel Coen, 2012, Valor de ley, with 51 occurrences in the source text) and Django Unchained (Quentin Tarantino, 2013, Django desencadenado, with 16 occurrences), where they were always translated as marshal in the Spanish dubbed version.

Notwithstanding, the evolution of other terms foregrounded at the beginning of the previous chapter did influence the versions dubbed into English. Even though the calque whisky was generally used to refer to the canonical alcoholic drink served in Western saloons, a new calque, burbón, unexpectedly appeared to refer to “bourbon,” a term which had not been used a single time in the fifteen American Westerns. For instance, in the fourth film of the corpus of Euro-Westerns, Una tumba para el sheriff (1965, Lone and Angry Man), it is compulsively uttered five times between minutes 00:06:50 (10; ¡Un burbón!) and 00:13:50 (11; El burbón nos da asco.) within the premises of the salón (dubbed into English as “bar” in this film). In the English dubbed version, we can find four instances of “bourbon” in that fragment (the fifth occurrence is omitted), which is remarkable for an American culture specific item which had never appeared in the corpus previously analyzed: (10) “Bourbon!”; (11) “Bourbon’s for cheapskates.”

In the following film of the corpus, 7 dólares al rojo (1966, 7 Dollars on the Red), there was a return to whisky as the customary drink, but another unexpected liquor was incorporated to the corpus, again non-existent in the fifteen American Westerns mentioned above:

This wine of Spanish origin did exist in the USA in the 19th century; actually, “sherry” is an anglicization of the Spanish word jerez. This time, the Anglicism was not included in the Spanish script; the whole maneuver could be interpreted as a minor nationalistic stance to promote the Spanish wine in a foreign context. On the whole, the outstanding issue is the incorporation of liquors in the versions dubbed into English which had never appeared in the corpus of original American Westerns. In the latter film, we can also find tequila due to the inclusion in the plot of an archetypical Mexican bandit usually played by Spanish actor Fernando Sancho (Aguilar, 1999).

As for the final word from that opening list of examples of the previous chapter, the hypernym “gun,” the most outstanding issue is the widespread use of the Anglicism revólver (twenty-three times by Spanish scriptwriters), which was derived from the English word “revolver,” which, as mentioned above, had not been used a single time in the fifteen American Westerns compiled for the previous corpus. A consequence foregrounded in this research is that this latter word did seep into the versions dubbed into English of Euro-Westerns. In Brandy, for instance, we can find the use of the term in English.

In the three other occurrences in which revólver is used in the original Spanish version of Brandy (the name of the main character in the film, not a reference to the liquor), it is translated twice with the canonical hypernym “gun” and once as “six-shooter”; so it was still far from becoming an established term in the English lexis related to Westerns, but it had made its first appearance.

Expletive language could not be found in Spanish scripts, as it was severely controlled by the fascist dictatorship. In fact, Spanish productions or co-productions of Euro-Westerns (or any other genre) had to go through such a lengthy administrative process until they got the official permission for distribution from the Spanish Censorship Board that sometimes they were released abroad earlier than locally (for instance, Django was released a year earlier in the US, 1966, than in Spain, 1967). Once the Motion Picture Association of America had modified its rating system, there seemed to be an attempt to fulfill the expectations of the foreign market of Spanish Euro-Westerns in that linguistic field. Hijo de perra, developed in Spanish dubbing translations since the repeated use of “son of a bitch” in The Wild Bunch, was used once that same year by Romero Marchent, the Spanish scriptwriter of Mátalos y vuelve (1969, Kill Them All and Come Back Alone), with no censoring consequences: (14) “-¡Hijo de perra! -Son of a bitch!” (00:56:30). However, other Spanish scriptwriters may have still felt uneasy about the term and came up with, for instance, (15) “hijo de Satanás” (son of Satan), translated as the not so normative “dirty low down dog” (00:17:00), in Arizona Colt Returns, which, like the customary euphemisms canalla and bastardo, present, respectively, in 7 dólares al rojo and Django, would never be used in everyday Spanish. A different case can be found in El hombre de Río Malo (1973, Bad Man’s River) when the still unsteady lexical loan switches gender in the original Spanish script, (16) “¡Hijo de perro!” (00:27:20), being subsequently, but not very normatively, dubbed into English as “Son of a dog!”

Incomprehensibly, the lexical loan translation developed in the dubbed version into Spanish of The Wild Bunch can be found once in the Spanish version of Por un puñado de dólares, written by Víctor Andrés Catena and released four years earlier, which would not be chronologically coherent with the development of the Spanish lexis and will require further research:

As mentioned above, it must be taken into account that censorship under Franco’s regime greatly influenced creative work in Spain, and its consequences can still be appreciated. Romero Marchent claimed that Spanish Euro-Westerns were an indirect consequence of Franco’s censorship (Aguilar, 1999) in the form of mild resistance to it by Spanish professionals who participated in multinational co-productions whose plots were fictitiously located in a different country. The most outstanding case can be found when contrasting the Spanish and English versions of Oro maldito (1967, Django Kill…If You Live, Shoot!).

Suicide was taboo during the Spanish fascist regime, strongly influenced by the Catholic church, so the reference to it in the Spanish script would have been censored and replaced with an allusion to an accident. However, the former reference remains in the dubbed version into English, perhaps because the pre-censored original dialogues were used for the translation for dubbing into English. Later in the same film we can also find:

(19) Quizás por eso el señor ha querido castigarle con la muerte de su hijo. En el pueblo sentó muy mal cuando se casó con esa mujer. Y encima la tiene en la taberna cantando para cuatro borrachos. (01:12:10)

That’s why the Lord struck down his son. He lives with that woman openly and they are not married. It’s a scandal everyone talks about.

Another taboo issue was the notion that a man and a woman could cohabitate without being married, so the Spanish censored version made them husband and wife. Again, the English version seems to have followed the original uncensored script.

The censored version of this Euro-Western is still commercialized on dvd in Spain; the latest edition is dated 2014, and the distorted dialogue in Spanish remains. One, therefore, has to watch the version of this and other films dubbed into English to find out what they were originally about, which would prove to be yet another example of the lasting legacy of Franco’s regime in contemporary Spain.

As Gutiérrez Lanza (1997, p. 40) points out, “During Franco’s dictatorship (…) dubbing is one indication that translation was not really a target-audience oriented activity, but one that would meet the needs of the people in favour of the maintenance of a particular status quo.” The Spanish Catholic church was an institution that supported the maintenance of this status quo with the presence of several of its members in the Comisión de Censura Cinematográfica (Gutiérrez Lanza, 1997, p. 43) and exerted its influence on a wide range of issues. As has been seen concerning the terminology used to refer to churchmen in American Westerns dubbed into Spanish, the term “reverend,” which could refer to clergy from different faiths, had been duly translated as reverendo in Stagecoach, as it was also done in The Horse Soldiers, even though the normative terms in Spain are either sacerdote or cura. Other terms such as “preacher” or “deacon” to refer to churchmen who appeared in American Westerns were translated, respectively, with the equivalent predicador or, in the latter case, surprisingly with the Latin term páter. However, in Spanish Euro-Westerns, where local censorship had a more direct access to the creative work of Spanish scriptwriters, a new term was incorporated to clearly specify that the members of the clergy portrayed in them belonged to a different religion, pastor, perhaps because this typology of character eventually became more dubious in the sub-genre.

Pastor can be found for the first time in Brandy, where it was normatively translated twice into English as “reverend”; there is one occurrence of reverendo in this film as well, expectedly with the same translation. However, in the tenth film of the corpus, Quince horcas para un asesino (1969, Fifteen Scaffolds for a Murderer), we can also find “pastor” in the dubbed version into English:

(20) No, antes los ahorcaremos y después ya serán juzgados, pastor Ferguson. (00:27:16) No, first we hang them, then we can judge them, pastor Ferguson.

As this typology of characters became more and more extravagant, played by major European stars such as Franco Nero (¡Viva la muerte…tuya!; 1973, Long Live…Your Death!) and Francisco Rabal (En el Oeste se puede hacer… amigo), the need to specify that they had no connection with the Catholic church became more relevant, as we can see in an extract from the former film:

This is the only time that the normative Spanish word sacerdote appears in either corpora of versions dubbed into Spanish or original Spanish scripts; it would be considered acceptable here, since it is used to provide a positive perspective when compared with the clergy of a different faith. As for pastor, it also appears in the dubbed version into English of this and other successive Euro-Westerns. Finally, it must be pointed out that the customary meaning of pastor in Spanish, shepherd, leads to a polysemic joke that does not translate so well into English; it is a recurrent resource also used in En el Oeste se puede hacer… amigo. The conclusion would be that the strict censorship of Franco’s regime also had linguistic consequences in the canonical lexis of Westerns in English-speaking countries, since the dubbed Euro-Westerns incorporated terms which cannot be found in the corpus of original American Westerns.

Overall, the alleged main aim of dubbing Euro-Westerns into English to avoid the alienating effect of watching a Western with dialogues in Spanish may not have been totally fulfilled. The use of lexical elements which were practically non-existent in original American Westerns, such as “pastor” or “revolver,” would have produced an unexpected semantic noise (Jakobson, 2000) and, consequently, a linguistic alienation in the new target context as well as the issue of the noticeably imperfect dubbing (Hughes, 2010; Newbould, 2019) which might have taken English-speaking audiences aback. The speech community (Spolsky, 1998) of the genre in English-speaking countries had its own norms, standardized diachronically by American Westerns; and if the versions dubbed into English of Euro-Westerns disrupted them in any way, the alienating effect would be unavoidable.

Results

In addition to the translation pairs that result from the two parallel corpora mentioned in the section devoted to the corpora, whose analyses reveal a non-normative influence of the lexis of the source texts on the dubbed versions (far more numerous in the Spanish target context), a comparable corpus between versions dubbed into Spanish of American Westerns and original Euro-Westerns in Spanish enables US to verify how scriptwriters of the latter took a step forward in the development of the artificial dubbese, moving further away from the norms of usage of their source language.

Moreover, another comparable corpus bringing together original scripts of American Westerns and Euro-Westerns dubbed into English has finally enabled the verification of how the Spanish dubbese pervaded, to a lesser degree, the English canonical lexis of the original genre because of the influence of calques and of censorship restrictions in the Spanish sociocultural context. The results have been proven with the alignment of source and target texts developed throughout the analysis of the corpora.

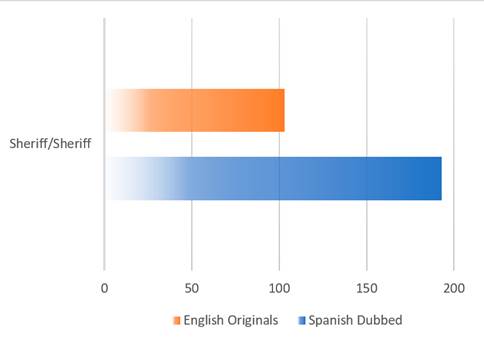

In order to illustrate these results, some sample diagrams are presented (see Figures 6 to 9). For instance, Figure 6, which makes use of the parallel corpus of American Westerns and their versions dubbed into Spanish, will contribute to understand the overwhelming popularization of the Anglicism sheriff, even though a Spanish equivalent such as alguacil could have been used.

Figure 6

Occurrence of the Word Sheriff in American Westerns and in their Versions Dubbed Into Spanish

The far more recurrent use of sheriff in the versions dubbed into Spanish is due to the fact that other figures of authority such as “marshal” or “deputy” were also translated with that term, which would explain the results. The fact that the former term was coined marshal by Spanish scriptwriters as a local word and finally had an influence on Spanish dubbing translators, who started incorporating it to their target texts, would be a further confirmation of the foreignizing intention in the Spanish cultural context.

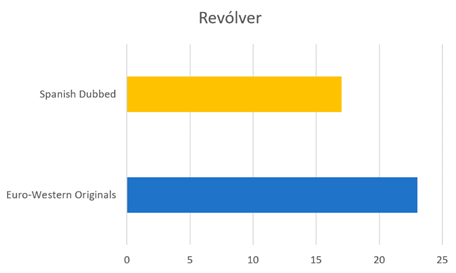

Figure 7 shows a result of the analysis of a comparable corpus made up of versions dubbed into Spanish and original Spanish scripts of Euro-Westerns, where it can be observed how an Anglicism, which was practically non-existent in the source texts of American Westerns, was developed in Spanish translations with a subsequent effect on Spanish screenwriters who contributed to expand it.

Figure 7

Occurrence of the Word Revólver in Versions Dubbed into Spanish of American Westerns and in Euro-Westerns

The most outstanding issue here is to analyze the evolution of Anglicisms developed solely in the Spanish cultural context, since “revolver” does not appear a single time in the source texts which make up the corpus of fifteen American Westerns. The fact that this term did eventually appear in the dubbed English versions of Euro-Westerns would also confirm the influence of the dubbese present in the original Spanish scripts upon the English translations for dubbing.

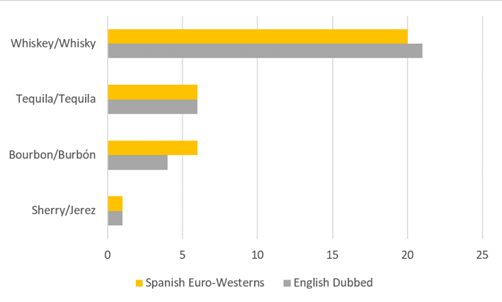

Consequently, the use of a parallel corpus made up of the Spanish original scripts of Euro-Westerns and their versions dubbed into English (Figure 8) also enables the analysis of how other words found their way into what could be considered an English dubbese.

Figure 8

Occurrence of Terms which Refer to the Semantic Field of Liquors in Euro-Westerns and in Their Dubbed Versions Into English

The presence of tequila is justified in Figure 8 by the inclusion of archetypical Mexican bandits in Euro-Westerns; but the fact that the calque burbón generated the presence in dubbed English versions of “bourbon,” non-existent in the corpus of American Westerns, must also be noted.

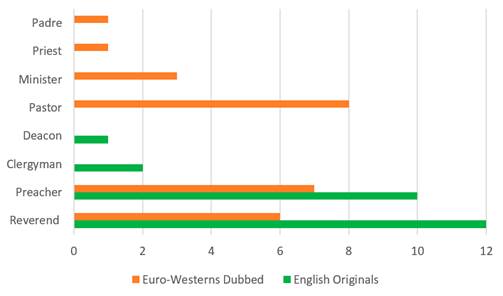

Finally, the analysis of a comparable corpus between the original American Westerns and the versions of Euro-Westerns dubbed into English (Figure 9) can also give an account of how previously unusual or non-existent terms in the lexical canon of the genre seeped into the dubbed versions, in this case, indirectly allowing the Spanish censorship to have an influence upon the versions dubbed into English.

Figure 9

Occurrence of Terms which Refer to Churchmen in American Westerns and in Dubbed Versions into English of Euro-Westerns

The dominant presence of “pastor” in the target context as a result of the dubbing of Euro-Westerns would prove that Franco’s censorship had exerted a linguistic effect beyond Spanish borders upon established democracies. On the other hand, the reverse effect would be that these Spanish productions dubbed into English and released uncensored abroad allow US to discover, even nowadays, the original content of the Spanish scripts that were modified by Franco’s regime.

Conclusion

The foreignizing tendency appreciated in Spanish dubbing translations and scripts of Westerns would also have an effect to a lesser degree on English dubbing translations of Euro-Westerns due to their use of uncommon terminology concerning the genre in the form of English normative terms that had not been used in the corpus of American Westerns. This did not seem to be an intentional approach, but rather the opposite.

In what initially seemed to be an attempt to naturalize Euro-Westerns by dubbing them into English, mainly for the American film market but also for other markets, the fact that terms were used in English-dubbed versions that cannot be found in American Westerns would be due to an unsuspected influence of the lexis used in the original Spanish scripts upon the target context language. The dubbese found in the English versions of Euro-Westerns would then be a consequence of a partial unawareness of the canonical language of the original American genre, which can be verified observing the presence of Anglicisms from the Spanish linguistic canon of the genre which are non-existent in the corpus of American Westerns. A further inclusion of more productions to the current corpora in due course will contribute to narrow and specify the generalized observations included in this article.