Introduction

This article deals with the translation for subtitles of foul language into English. This is a segment where it appears to be a certain terminological confusion since there is a lack of established metalanguage to talk about it (Wajnryb, 2005) and a truly remarkable variety of terms such as bad language, coarse language, foul language, offensive language, profane language, strong language, taboo language, or vulgar language. Given this disparity, the terms foul language, offensive language, and strong language were chosen and will be used interchangeably in this paper. The term swearword(s) will also be used, even if these can be considered a subcategory of the previous (Ávila-Cabrera, 2015b), to refer to a unit or instance of foul language rather than the concept in general.

Other terms were discarded based on their definitions. For instance, bad language can go beyond words and encompass grammar or dialects considered incorrect or that may have negative connotations (Battistella, 2005). Taboo language, in turn, includes terms that are not necessarily inherently offensive because they are deemed (in)appropriate depending on the context (Ávila-Cabrera, 2015b). As regards vulgar language, it could refer to language of an intimate nature (Wajnryb, 2005) or used by unsophisticated or under-educated people (Jay, 1992); hence a subcategory of offensive language.

As Stapleton (2010) puts it, “swearing is forbidden and carries the risk of censure” (p. 290). Despite this, strong language persists in constituting a vital part of languages and cultures both in everyday conversation and audiovisual content, in which it is constantly and increasingly present (Fuentes-Luque, 2015). Therefore, it seems worth looking into the translation of foul language, particularly in subtitling, as it presents unique challenges such as conveying a predominantly oral feature of speech in writing and a restricted context. Indeed, as claimed by Díaz Cintas (2001), dealing with strong language is, unquestionably, one of the most complicated tasks of subtitling. Other factors are subtitling’s vulnerability, cultural differences in the degree of tolerance to swearing or what is considered taboo, or finding the most appropriate equivalent in the target language (TL). Despite these difficulties, the adequate rendering of foul language is vital for the appreciation of translated audiovisual products (Pérez et al., 2017). As reported by Scandura (2004), some viewers taking part in a small-scale survey about subtitling and censorship in a cinema in Buenos Aires (Argentina) expressed that partially or not rendering strong language in subtitles “changed the essence of the programme” (p. 132).

The study of audiovisual translation (AVT) into English is gaining importance since it is increasingly needed and practised. This occurs because non-English language productions are becoming more popular in English-speaking countries thanks to the internet (Zanotti, 2018) and, more specifically, through video-on-demand (VoD) platforms. In Anglophone countries, “the most established AVT modality” is subtitling (Perego & Pacinotti, 2020, p. 43); however, this practice lacks sufficient research-backed guidelines (Díaz-Cintas & Hayes, 2021), hence the need to explore it.

Notwithstanding all this, academic research on foul language subtitling into English is insufficient. Some preliminary work was done by Díaz-Cintas and Remael (2007), but there are very few studies addressing this (e.g., Ávila-Cabrera & Rodríguez-Arancón, 2018; Gedik, 2020). Consequently, in this context of research on subtitling into English, it is relevant to consider offensive language. Swearwords in subtitling have been studied more comprehensively from English into other languages such as Spanish (e.g., Ávila-Cabrera, 2015a, 2015b; Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2007; Valdeón, 2015), Arabic (e.g., Alsharhan, 2020; Hawel, 2019), or Chinese (e.g., Chen, 2004; Han & Wang, 2014). Nonetheless, it still remains an under-researched area (Fuentes-Luque, 2015).

This article explores the translation of foul language in subtitles translated from Spanish into English1 subtitling aiming to conduct a descriptive analysis of the subtitling of swearwords spotted in Netflix’s Spanish comedy series El Vecino (Vigalondo, 2019‒2021) in order to determine how strong language may be subtitled into English. The research design was based upon the following two research questions:

-

How many instances of offensive language found in the source text (ST) were (not) transferred to the target text (TT) and which translation technique was used for this purpose?

-

Were there any omissions of strong language? If so, why were they omitted?

A corpus of 120 instances of foul language was compiled to conduct a quantitative and qualitative analysis from an empirical and corpus-driven approach. The corpus is composed of relevant extracts taken from the first three episodes of El Vecino and their English subtitles. It was classified according to their communicative function and transfer of their offensive load (OL) into the TL.

Following this introductory section, a three-section theoretical framework of relevant key concepts and issues is presented. This is followed by a description of the data set studied and the data collection methods employed to compile the corpus. Next, the results of the quantitative analysis of subtitling techniques used for foul language are shown, which answers RQ1. In this respect, results indicate that OL was transferred to the TL subtitles in most cases even if omission is the second most frequently used technique. A qualitative analysis of several examples is also offered to answer RQ2. Here, issues such as subtitling’s vulnerability, kinesic synchrony and the function of swearwords are examined as potential reasons to omit certain swearwords. Last, the conclusions drawn from this study can be found.

Theoretical Framework

The following sections present and discuss key concepts and issues dealt with in this paper, namely subtitling, foul language, the restrictions and challenges of subtitling foul language, and the techniques available to do so.

Subtitling

Subtitling is a highly complex activity due to the number of restrictions that it entails. These include time and space constraints, linguistic restrictions and simplification, code switching, isochrony, kinesic synchrony, and the preservation of the original soundtrack (see Ivarsson & Carroll, 1998; Díaz Cintas, 2001; Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2007). However, to keep the theory presented relevant to the analysis, this article will focus on three key aspects: code switching, spatiotemporal constraints, and subtitling’s vulnerability.

Firstly, subtitling involves converting oral speech into written text (code switching). Written texts are more linguistically-formal and standardised (Díaz Cintas, 2001), hence less expressive and spontaneous than oral texts. Additionally, since processing information takes longer when conveyed through written language (Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2007; Perego, 2008), there is a need to reformulate and omit some of it due to time and space constraints. Consequently, certain linguistic elements tend to be omitted in subtitles, primarily, features of oral discourse such as discourse markers, vocatives, repetitions, interjections, or modal particles (Chaume, 2004; Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2007). This includes swearwords since these can sometimes act as discourse markers or fillers. This is the most important if we consider that on Netflix, character limitation is set at 42 per line and reading speed at 20 characters per second in adult programmes (Netflix, 2021).

Additionally, in Gottlieb’s (1994) words, “subtitling is an overt type of translation, retaining the original version, thus playing itself bare to criticism from everybody with the slightest knowledge of the source language” (p. 102). This is known as subtitling’s vulnerability (Díaz Cintas, 2003). As a result, subtitlers are not only conditioned by spatiotemporal restraints, but also by the scrutiny of viewers, especially, those with knowledge of the source language and unfamiliar with the intricacies of translating and subtitling. Indeed, the nature of subtitling does not always allow the preservation of every linguistic element, normally, because of the need for condensation (Botella Tejera, 2007). Moreover, translations cannot always be literal (Chesterman, 1997; Hurtado, 2001), particularly, in contexts involving “spoken idiomatic language” (Newmark, 1988, p. 31) such as most audiovisual products. Lastly, subtitling vulnerability can be even more prominent on DVD or VoD platforms as the audience can hit pause and dissect the subtitles or even compare them with the dubbed version of the product (Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2007), which usually do not match because the constraints and priorities of both AVT modalities are dissimilar.

Foul Language

Briefly, offensive language is closely associated with swearwords (Ávila-Cabrera, 2015b; Battistella, 2005; Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2007), which are seen as the linguistic realisation of taboo subjects (Beseghi, 2016; Stapleton, 2010). These encompass also what can be considered inappropriate or unacceptable in certain circumstances or cultures (Ávila-Cabrera, 2015b) and thus, they are “restricted or prohibited by social custom” (Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2007, p. 194). Thus we may say that the concept of strong language covers a wide range of words and topics.

Several classifications of foul language have been proposed (e.g., Andersson & Trudgill, 1990; Ávila-Cabrera, 2015a; Battistella, 2005; Jay, 1992; Wajnryb, 2005). For the purposes of this paper, two taxonomies are used. Firstly, foul language can be classed into three categories according to the topic or sphere from which they originate (Battistella, 2005, p. 72), namely, as epithets, profanity, or vulgarity/obscenity.

Epithets are “various types of slurs” (Battistella, 2005, p. 72) that can refer to race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, appearance, disabilities, or other characteristics. Some examples include “bitch”, “fag”, or ‘retard’. Based upon corpus observation, epithets can also refer to animals (‘pig’) and family (‘son of a bitch’) (Jay, 2009) (see Table 2).

Profanity is “religious cursing” (Battistella, 2005, p. 72). It entails the use of religious terms as swearwords with no intention to denigrate religion. For instance, “hell”, “damn”, “God”, or “Jesus” are profanities (Wajnryb, 2005). It seems interesting to mention blasphemy here, as it is also connected with religious cursing yet intends to vilify religion or religious figures. A case in point is “Jesus fucking Christ” (Ávila-Cabrera, 2020).

Vulgarity/obscenity refers to “words or expressions which characterize sex-differentiating anatomy or sexual and excretory functions in a crude way, such as shit and fuck” (Battistella, 2005, p. 72). Although vulgarity is broader than obscenity, both are generally used interchangeably (Wajnryb, 2005).

Secondly, foul language can also be categorised according to the function fulfilled in each communicative exchange (Andersson & Trudgill, 1990; Pinker, 2007). Indeed, as Stapleton (2010) asserts, “swearing fulfils some particular communicative functions, which are not easily accomplished through other linguistic means” (p. 290). In this respect, four categories have been proposed by Andersson & Trudgill (1990):

-

Abusive swearing takes place when using slurs, name-calling, and other cursing expressions to offend and cause insult (Jdetawy, 2019, p. 27051).

-

Expletive swearing is an expression of emotions or attitudes that is not directed towards others but simply vents emotion (Jdetawy, 2019, p. 27051).

-

Humorous swearing is directed towards others but is “playful” and “humorous” rather than offensive (Jdetawy, 2019, p. 27051).

-

Auxiliary swearing is not addressed to others either (Jdetawy, 2019, p. 27051) but rather serves as an intensifier. It does not necessarily have negative connotations ―sometimes it can emphasise positive feelings (Grohol, 2009), or simply constitute a casual conversational habit adopted to fit in (Jay, 2009). However, it “can still be regarded as impolite or offensive” (Jay, 2009, p. 155).

Having observed the corpus, adding a fifth category was deemed necessary: descriptive swearing (Pinker, 2007), which consists in using strong language with its literal meaning; thus, it fulfils a referential function that contributes to plot development. An example is the sentence “let’s fuck”.

Examples of the swearing sorts discussed above are shown in Table 1 while Table 2 summarises both taxonomies of foul language addressed here.

Table 1

Types of Foul Language According to their Communicative Function

[i]Source: Adapted from Jdetawy (2019), Jay (2009), and Pinker (2007).

Table 2

Taxonomy of Foul Language Depending on Topic and Function

| Topic From Which It Originates | Function That It Fulfils |

|---|---|

| Epithet Profanity Vulgarity/obscenity | Abusive Expletive (or cathartic) Humorous Auxiliary (or emphatic) Descriptive |

The first taxonomy classifies swearwords according to the topic from which they originate and is used to establish which words can be considered strong language. It appears sufficient for the purposes of this paper as it covers all the instances conforming the corpus. Nonetheless, swearwords are not necessarily limited to these spheres. As Montagu (1967, p. 90) puts it, “[a]ny word carrying an emotional charge is capable of serving the swearer as ammunition for [their] purposes.” The second classification proposal, which categorises foul language based upon its function, is used to helps elucidate the reason to omit some swearwords in subtitling (see research question 2). Given the different functions that they can fulfil, it could be argued that some may be considered more relevant than others in terms of narrative value, which might influence the choice for omission.

Restrictions and Challenges in Subtitling Foul Language

As stated previously, strong language is an integral part of everyday speech and spoken audiovisual discourse. Its subtitling is not governed solely by the constraints characteristic of this practice but also by factors of ideological or cultural nature (Fawcett, 2003).

Firstly, censorship, which “constitutes an external constraint on what we can publish or (re)write” (Santaemilia, 2008), can affect this practice. Nevertheless, this is not the case in present-day English-speaking countries as there are no censorship measures in place such as those existing in politically or religiously oppressed environments. In this cultural context, the subtitling of swearwords may be influenced by the requirements set out by commissioners, tv channels, or av content distributors (Díaz Cintas, 2001; Mattsson, 2006), which are normally a reflection of each culture’s norms and view of the world (Mattsson, 2006). However, according to Netflix’s guidelines, “[d]ialogue must never be censored” and subtitles must “[a]lways match the tone of the original content” (Netflix, 2021). Thus, since the corpus was extracted from this VoD platform, censorship imposed by the client is not considered a potential factor contributing to the omission of foul language in this case.

Yet, censoring is not necessarily conditioned only by external pressures. It can also occur by ideological or cultural circumstances, thus becoming “an individual ethical struggle between self and context” (Santaemilia, 2008, pp. 221‒222). This struggle stems from the fact that every culture has different taboos (Fuentes-Luque, 2015; Parini, 2013). Since translators tend to “operate first and foremost in the interest of the culture into which they are translating” (Toury, 2012, p. 6), they might sometimes function as self-censors, voluntarily or involuntarily, by producing translations that are socially and personally deemed “acceptable” in the target culture (Santaemilia, 2008). In this respect, Spanish speakers seem highly tolerant of strong language on screen (Pavesi & Zamora, 2021), more so than English speakers; according to Valdeón (2015, 2020), Spanish dubbed versions of English-language audiovisual products usually increase the offensive load (OL). This could derive from factors such as cultural differences or the frequency of the use of swearwords in each language. For instance, Dewaele (2004) presents the testimony of a bilingual person who asserts that “Spanish speakers seem to be able to insult one another without anybody getting very upset whereas in English you would make enemies for life” (pp. 214‒215).

Moreover, given the cultural specificity of offensive language, reflecting it in the target product can constitute a major challenge. This is because determining the degree of offensiveness of swearwords and finding an adequate equivalent for the target culture can be difficult (Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2007). Despite this difficulty, researchers commonly advocate their preservation in the TT (e.g., Chaume, 2004; Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2007; Greenall, 2011; Santaemilia, 2008). One reason is that omitting swearwords can potentially alter the reception of the target product and the perception of the characters given their substantial cultural, social, and subjective load. Thus, “the correct translation and adaptation of foul language in audiovisual products is of the utmost importance” (Pérez et al., 2017, pp. 72‒73).

Furthermore, “a character’s speech is an important part of [their] personality” (Tveit, 2004, p. 16). Swearing can be an indication of aspects such as age, social class, level of education (McEnery & Xiao, 2004), emotional state, or the relationship among interlocutors (Vingerhoets et al., 2013). Nonetheless, attempting to impose the value system of a culture onto another is “dangerous ground” (Bassnett, 2013, p. 33), and the target culture’s moral patterns may differ from the source culture’s. Plus, they may not always be suitable for the translation of foul language. For example, as explained earlier, Spanish speakers are quite lenient with insults while English speakers would generally feel deeply offended. Hence, some changes resulting from the translation process may be unavoidable.

Another issue influencing the subtitling of strong language is the previously mentioned concept of subtitling vulnerability. In Scandura’s (2004) words, “[w]hen watching subtitled material, audiences often feel they are being cheated because they realise that what was said could not have been what was written in the subtitles” (pp. 125‒126). This can severely affect the perception of the product and the quality of the translation and may be unjustly criticised.

Finally, it seems interesting to draw attention to the findings of a survey conducted in Argentina after the viewing of a subtitled film (Scandura, 2004, pp. 131‒132). These findings largely coincide with the challenges and restrictions outlined here. When asked about the possible reasons for neutralising or omitting offensive language, some respondents (10 %) thought these actions were the result of legislation prohibiting the use of swearwords in translations, that is, censorship. Others thought it was done “out of respect for the audience” (25 %) so that children could also watch the programme (26 %), or because Latin Americans are “too puritanical” (10 %). In other words, they thought it stemmed from self-censorship for cultural or ideological reasons. The rest of the respondents did not know why these omissions or changes might have been made, but they did find that these were “unnecessary” and “changed the essence of the programme,” that is, the perception of the target product was indeed altered.

Rendering Offensive Load

As noted above, assessing the degree of offensiveness of swearwords and matching their meaning and OC in the TC can be challenging for several reasons. Therefore, according to Ávila-Cabrera (2015a), the impact of offensive words on the target audience depends largely on the translator’s decisions when subtitling each instance of strong language (p. 16). In this respect, there are five possible techniques2 to which the translator can resort (Ávila-Cabrera, 2015b, 2020).

The first one is toning down the OL in the subtitle, which is softened or partially transmitted, even though the translator tries to render it to some extent (for instance, by removing the swearword while preserving the allusion to a taboo topic). The second technique is preserving the original OL. The third one is toning up the OL. i.e., enhancing the degree of offensiveness of the TT with respect to the ST’s. This can also encompass cases in which there was no OL at all in the ST but there is some in the TT (Ávila-Cabrera, personal communication, November 24, 2021). In any case, this is generally done to compensate for some previous loss. The fourth technique is neutralisation of the OL as a result of replacing the swearword with a non-offensive word. The fifth one is the omission of OL by deleting the swearword. Table 3 shows examples of each translation technique.

Table 3

Examples of Offensive Language Translation Techniques

Ávila-Cabrera (2015b, 2020) considers that the first three options result in OL’s transmission whereas the last two entail the loss of that load in the TT (see Table 4). Although Ávila-Cabrera’s (2020) proposal derives from analyses of foul language in the subtitling of English into Spanish, it is deemed appropriate and sufficient as a starting point for examining this phenomenon in the reverse language combination. Thus, this will be the basis to determine whether the OL of instances of strong language detected in this corpus is transferred or lost in the subtitles, carrying out a quantitative analysis (see research question 1).

Table 4

Taxonomy of Techniques to Translate Offensive Language According to the Transference of OL

| OL is transferred | OL is not transferred |

|---|---|

| Toning down Preserving Toning up | Neutralising Omitting |

[i]Source: based on Ávila-Cabrera (2020, p. 129).

Method

Given the nature of the research questions that this paper seeks to answer, a descriptive study has been conducted based on quantitative and qualitative methods. The specific research questions posed can be found in the introduction.

The first research question (RQ1) was addressed by documenting the number of instances and establishing which of these techniques are used to convey foul language from the ST, e.g., no attempt, toning down, “equivalent” TL usage, etc. Regarding the second research question (RQ2), it was tackled by detecting the cases of omission in the corpus and carrying out qualitative analysis to assess the potential reasons behind this decision, e.g., whether aspects such as the communicative function of the swearword or its phrasing may have played a part in choosing to omit it.

Since this study provides new data derived from observation, an empirical perspective and a corpus-driven approach (Saldanha & O’Brien, 2014) were adopted. The examined corpus―both the ST in Spanish and the English subtitles―was extracted from the first three episodes of Netflix’s Spanish comedy El Vecino (Vigalondo, 2019‒2021) broadcast in the UK.

The choice of this show to do the analysis stems from the personal experience of the researcher as a viewer, it is stated that this product contains sufficient and fairly varied examples of foul language. Variety constitutes a desirable trait of corpora in the field of Translation Studies because it results in “a balanced representation of the population” (Saldanha & O’Brien, 2014, p. 73) and, thus, in studies “with a much greater power of generalization” (Alves & Hurtado, 2010, p. 34). Additionally, this show was produced recently, so the findings derived from examining it can be considered relevant as they conceivably reflect the television industry and subtitling practices of the present.

The sample consists of 120 units of selection and 127 units of analysis, which is considered appropriate in size given the scope and purpose of this paper. The examples were selected based primarily on the first taxonomy of strong language that classifies swearwords according to the sphere from which they originate. Hence, those words or expressions that fall under the category of epithet, profanity, or vulgarity were included in the corpus. Regarding the corpus compilation procedure, it consisted of the following actions: viewing the product, detecting potential examples of foul language, assessing their suitability as such, making notes of information relevant to the analysis of each instance, and classifying them according to their function in the communicative exchange and the degree of transference of OL to the TL. Table 5 displays a sample of the corpus.

Results and Discussion

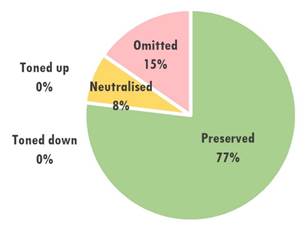

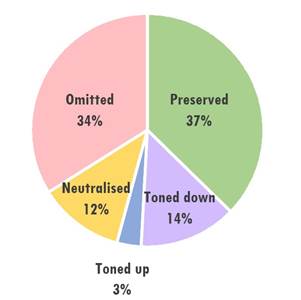

The following quantitative analysis establishes the frequency with which the OL of foul language was rendered in the TL subtitles of the first three episodes of El Vecino and to what extent it happened. All the analysed instances are illustrated in the form of two pie charts (Figures 1 and 2). It is worth pointing out that humorous swearing will not be commented upon as no examples were spotted in the corpus examined.

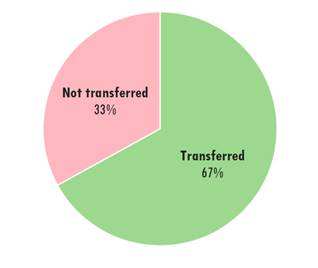

Figure 1 shows the frequency with which the OL of the ST was transferred to the TT. In response to RQ1, out of the 127 instances examined, the OL of 85 of them (nearly 67 %) was found to be transferred from the ST to the TL subtitles whereas in the remaining 42 cases (roughly 33 %) that did not occur.

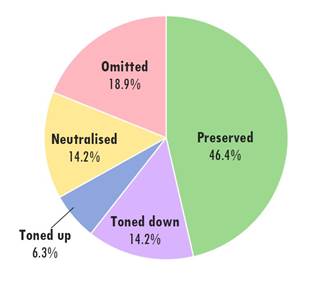

Figure 2 displays the frequency of use of each translation technique, i.e. to what extent the OL was (not) transferred to the TT. This responds to RQ1 as well. First, the OL of 59 examples (46.4 %) was preserved, which implies that, in this corpus, preserving the OL of swearwords in English subtitles is the most common scenario. The second trend is omission as 24 of the instances analysed (18.9 %) were eliminated in the TT. Next, 18 examples (14.2 %) of strong language are toned down, which coincides with the number of neutralised instances. Lastly, only 8 of the 127 instances detected (6.3 %) were toned up, thus making this the least common technique to subtitle strong language in Spanish into English.

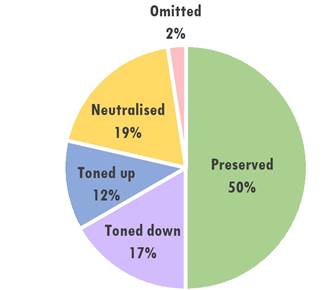

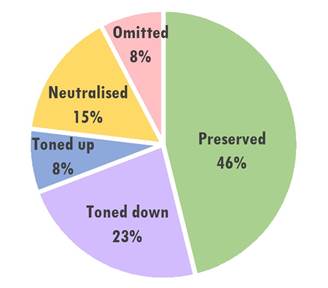

An additional quantitative analysis was performed to be used as a basis for the subsequent qualitative analysis. In this vein, Table 6 and Figures 3 and 4 present the frequency of use of each technique for each type of swearword (see Table 6, Figures 3 to 6).

Table 6

Frequency of Use of Each Technique Classified According to Kinds of Swearing

| Descriptive | Abusive | Expletive | Auxiliary | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preserved | 21 | 10 | 22 | 6 | 59 |

| Toned down | 7 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 18 |

| Toned up | 5 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| Neutralised | 8 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 18 |

| Omitted | 1 | 2 | 20 | 1 | 24 |

| Total | 42 | 13 | 59 | 13 | 127 |

This data will be further explained and used to establish whether the type of swearword (based on its function in the text) might influence translation decisions concerning the transfer of its OL and if so, how. For this purpose, a qualitative analysis was conducted with the aim of identifying possible patterns for the choice of each technique, focussing particularly on omitted strong language (see RQ2). Thus, the discussion presented below responds to RQ2.

First, as shown in Figure 3, descriptive swearing is most frequently preserved in TL subtitles although other strategies that maintain its semantic load such as neutralisation are also used; however, omission hardly ever happens. The reason could be that failing to transfer the meaning of the ST swearword in cases of descriptive swearing does not seem appropriate given its relevance to the plot. In these cases, it could be argued that the translator’s prime concern is to transmit the meaning because doing otherwise could result in the loss of information relevant for the audience to follow the story (Table 7).

Table 7

Descriptive Swearing Being Preserved in TL Subtitles

Table 8

Neutralisation Where the OL Was Not Rendered in the TL

Furthermore, as explained previously, omission alters the target audience’s emotional impact and perception of the product and the character as it does not render the original OL. This is also the case for neutralisation, which may explain the perception that it is normally reserved for cases where the OL of ST cannot be transferred. This is because there is no (natural) equivalent swearword or offensive expression in the TL ―yet the semantic load must be preserved. An example is the following:

Notwithstanding, in the following case, the OL is toned up since an utterance with no OL is replaced with another that has a similar meaning and is offensive (Table 9).

Table 9

Toning Up of OL

The example in Table 9 seems worth examining because the ST incorporates an extralinguistic cultural reference (ECR) ―a Spanish whisky brand―whose meaning and connotation are presented in the form of a swearword in the TT. Here, the translator opted for generalising the ECR (Pedersen, 2011), possibly, because this brand is not popular in English-speaking countries. Likewise, this could also offer the opportunity to incorporate a swearword in the TT given the negative connotation of this ECR (Table 10).

Table 10

ECR Rendered as a Swearword

| Example 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Instance 69 | |||

| OL | Toned up | ||

| Type of swearing | Auxiliary | ||

| Episode | ST | TT | Time stamp |

| S01 E02 | Pero... ¿pero esto qué es?[But... but what’s this?] | What the… // what the hell is this? | 13:06 - 13:09 |

In contrast, in this example, an expression with a certain OL was added to the TT despite the absence of one in the ST. In any case, toning up non-offensive language ―such as the ones in Tables 9 and 10― may be a way of compensating for omitting or neutralising some instances of strong language. As Díaz-Cintas and Remael (2007) point out, concerning marked speech -including swearwords:

[s]ubtitlers regularly apply the strategy of compensation when translating marked language. This means that a particular intervention becomes more ‘marked’ or ‘colourful’ in some subtitles, to compensate for the loss of such speech elsewhere in the translated film. (p. 186)

Despite subtitling’s vulnerability, this choice arguably contributes to the characterisation of the show and its speakers―and thus the reception of the target product―being as close as possible to the original.

Secondly, a tendency to transfer auxiliary swearing to the TL subtitles is observed (see Figure 4) -even if it tends to be is predominantly expressive and not as semantically relevant as other types- it does contribute towards characterisation, but it can generally be regarded as dispensable in terms of narrative value. Two examples of this are shown in Tables 10 and 11.

Table 11

Transference of Auxiliary Swearing to TL

Thus, if auxiliary swearwords were omitted in the TL subtitles, this decision should not prevent the target audience from following the story―in contrast with omitting descriptive swearing, for instance. Nonetheless, the emotional impact and portrayal of the character uttering this swearword would conceivably differ from that of the ST. Thus, similar to toned up instances, the translator may have chosen to preserve most instances of auxiliary swearing in an attempt to transmit these emotions and characterisation. Moreover, in both examples, Netflix’s character limitation (42 per line) did not pose a problem to the preservation or addition of these swearwords.

Next, as shown in Figure 5, the OL of abusive swearing is commonly transferred to the TL subtitles, possibly, due to its relevance to the plot and product. As a rule, abusive swearing is not only considerably expressive but also semantically loaded. It provides crucial information about the emotional state or the attitude of a character towards another and their relationship, which can normally have an impact on the development of the story. Table 12 brings an example of preserved abusive swearing.

Table 12

Abusive Swearing Transferred to TL

| Example 6 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Instance 24 | |||

| OL | Preserved | ||

| Type of swearing | Abusive | ||

| Episode | ST | TT | Time stamp |

| S01 E01 | ¡Es que eres gilipollas! [You’re a moron!] | You’re such a jerk! | 12:11-12:12 |

Moreover, these cases of abusive swearing might have been preserved also due to the multimodal nature of audiovisual texts, which are “a multi-channel and multi-code type of communication” since they use simultaneously both the acoustic and visual channels (Delabastita 1989/2015, p. 196) and combine verbal and non-verbal codes (Chaume 2004) to transmit a message. In this show, it has been observed that when a character uses abusive swearing, they tend to raise their voice, very obviously address the victim, and look angry. In other words, non-verbal information makes it fairly evident that the speaker could be insulting someone. Since the target audience perceives this information, it is quite probably taken into consideration when making translation decisions as omitting the swearword in these cases might result in a somewhat incoherent or confusing TT.

In fact, Table 13 shows one of the only two cases of omitted abusive swearing spotted throughout the corpus. The reason for this omission could be that this case is somewhat unusual since the target is not a character of the show, but the avatar of a videogame that is not even part of the story. This causes this instance of abusive swearing to have little to no narrative value. Additionally, the speaker does not display any of the non-verbal traits described above. Therefore, this particular non-transfer of OL should not, in principle, give the target audience a feeling of strangeness as it is not incongruous with the image and the paralinguistics of the ST; in other words, it does not rupture kinesic synchrony.

Table 13

Example of Abusive Swearing Omitted in the TL

| Example 7 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Instance 66 | |||

| OL | Omitted | ||

| Type of swearing | Abusive | ||

| Episode | ST | TT | Time stamp |

| S01 E02 | ¡Va, cabrón! [Come on, you bastard!] | Come on! | 12:19-12:20 |

Nonetheless, it is interesting to point out that in the other example of omitted abusive swearing found (see Table 14), omission happened yet it did not rupture kinesic synchrony even if the non-verbal traits are characteristic of an angry person. The reason is that the ST includes two abusive swearwords but only one of them is eliminated from the TT. In this case, one of them may have been deemed superfluous as they both fulfil the same communicative function, hence the omission. However, it should be borne in mind that, as explained above, the target audience’s perception of the product might still be altered. This is because the OL of the utterance is overall reduced (see Table 14).

Table 14

Reduction of OL in Utterance

In connection with expletive swearing, as Figure 6 displays, almost half (46%) of the instances detected in the corpus have not been transferred to the TL subtitles. This points to expletive swearing as the most likely to get lost in English subtitling translations, either by omitting or neutralising. Table 15 brings a case of preserved expletive swearing.

Table 15

Preserved Expletive Swearing

| Example 9 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Instance 44 | |||

| OL | Preserved | ||

| Type of swearing | Expletive | ||

| Episode | ST | TT | Time stamp |

| S01 E01 | ¡Hostia! [Shit!] | Holy shit! | 26:34-26:37 |

Here, the swearword was the only word uttered, thereby omitting it could create a sense of strangeness in the target audience due to the phenomenon of subtitling’s vulnerability. The audience perceive the ST but not the TL subtitle for it. Indeed, it has been observed that when a swearword is uttered on its own, it is normally preserved. It may also be neutralised in some cases but is never―at least in this corpus―omitted. Nonetheless, when it is not the only element making up the utterance, it tends to be omitted (Table 16).

Table 16

Omission of Swearwords

In the excerpt in Table 16, swearwords are not the only elements eliminated from the TL subtitles. The main reason behind these omissions could be that those elements conceivably act as discourse markers or fillers since the message is still the same after eliminating them. Additionally, given the ST’s length, Netflix’s character limitation would have probably been exceeded if all elements had been transferred to the TT. Thus, given their expletive function, lack of narrative value, and the need to condense this subtitle, the swearwords in this instance may have also been regarded as fillers and removed from the TL subtitles. Nevertheless, unlike other fillers, strong language carries OL. Therefore, even though omitting it may not affect the plot, as mentioned earlier, it might alter the target audience’s emotional impact, viewing experience, and perception of the characters and product.

Finally, it is worth nothing that the following example involves two different types of swearwords are combined in the same utterance (Table 17).

Table 17

Two Different Swearwords Combined in One Utterance

Here, the translator has decided to omit the swearword that fulfils an expletive function (i.e., joder) over the descriptive one (i.e., putada), arguably because, as already pointed out, expletive swearing does not normally contribute significantly to plot development. In this case, interestingly, both swearwords convey the same information: putada [pain in the ass] and joder [fuck] transmit a feeling of disappointment and frustration. This may have also influenced the translator’s choice to eliminate one since the message is conceivably accurately transmitted despite the loss of expressiveness and slightly decreased OL. Given the length of the ST, character limitation does not seem to be a reason to omit the expletive swearword in this case.

Conclusions

In this article, RQ1 sought to determine the frequency with which offensive language is (not) transferred to the TL subtitles and to what extent. Quantitative results indicate that OL has been transferred to the TL subtitles in most cases. Thus, although omission is the second most frequently employed technique, a tendency to transfer the original OL when translating foul language into English subtitles is observed. In fact, in this corpus, occasional attempts to compensate for omissions were detected. This is because some non-marked language was toned up and most auxiliary swearwords were preserved despite their predominantly oral nature and little impact on plot development. These suggest that the transfer of OL is taken into consideration and pursued to the greatest possible extent, which is in line with current academic recommendations for the subtitling of foul language and Netflix’s instructions against censorship.

RQ2 looked at the reasons behind the omission of certain instances of strong language in English subtitles. The qualitative analysis carried out allows to conclude that the selection of omission as a foul-language translation technique, in the context of Spanish-English subtitles, could result from or be influenced by subtitling’s vulnerability and other factors. Those factors ―to the best of the author’s knowledge― have not previously been studied in connection with the translation of strong language. Some examples are multimodality (i.e. kinesic synchrony) or the communicative function of each swearword. It could be inferred that time and space constraints of subtitling might not play a particularly central part in this case; yet, since subtitling software could not be used to analyse these subtitles, this is simply an assumption that may be desirable to verify.

Even though this study establishes a basis for further studies in the field, some limitations were encountered, which give rise to valuable ideas in this sense. Firstly, given the limited number of examples of omission detected (24) and the scarce research on subtitling strong language into English, it would be worth expanding the corpus or conducting this analysis on other subtitled products to have broader information available. Apart from that, due to the impossibility to use a subtitling editor, the impact of character limitation on the omission of strong language has not been assessed thoroughly enough. This comes across as an interesting research avenue as well as reception studies. These would also be useful as they could shed light on how foul language in English subtitles is being perceived by viewers.

Additionally, research focused particularly on censorship is desirable, considering that these factors could not be discussed here due to their complexity and the scope of this article. First, as pointed out in the Restrictions and challenges section, Spanish speakers may be more comfortable than English speakers with strong language in audiovisual products. Research on this could help to elucidate whether and to what extent self-censorship due to cultural differences influences omissions of strong language in subtitles into English, or whether factors such as age group or frequency of use of foul language in each language might play a role in people’s degree of tolerance of strong language. Lastly, it would be interesting to analyse the subtitling of foul language into English on tv channels or VoD platforms other than Netflix―which, as mentioned earlier, does not impose any restrictions in this respect―to establish whether external constraints may constitute a reason for omitting foul language in other contexts