Introduction

It is well known that commercial EFL textbooks have prevailed as the main resource for English teaching and learning. However, these resources have overlooked the changing and diverse complexity of historic, socio-cultural, political, economic, educational, and aesthetic realities and concerns of local contexts. For instance, their potential to promote comprehension of cultural diversity is arguable. In this framework, this study analyses instrumental, homogenised, decontextualised, and colonised EFL textbooks regarding the dimensions of being, knowledge, and power, with the supremacy of global culture. In this sense, it embraces desirable, contextualised, and decolonised EFL materials otherwise sensitive to cultural diversity.

The decolonial turn proposes a thought otherwise (un pensamiento otro) also known as a border thought (pensamiento fronterizo). This oppositional thought is not simply based on recognition or inclusion, but rather centred on a socio-historical structural transformation. For the context of this paper, this also implies teachers otherwise, students otherwise, and EFL materials otherwise. These latter are conceived from a reflective, critical, and emancipating stance to respond to diverse social dynamics and cultural patterns of local contexts where these resources are used to teach and learn English. They also relate to other cultural experiences of the world.

By the same token, curriculum, materials, assessment, language policy, and teaching and practices oriented by critical interculturality are vital for EFL and ESL teaching and learning. Thence, it is crucial to reassess them as “socio-cultural, pedagogical, didactic, and cognitive mediations that facilitate linguistic and cultural interactions” (Núñez-Pardo, 2020a, p. 114). These mediations have the potential to educate critical and interculturally aware citizens and nurture disruptive mindsets able to transform complex realities. In this vein, this article attempts to encourage English teachers to challenge the belief that they are consumers of knowledge; instead, they should be seen as critical, political, knowledgeable, and transformative subjects (Freire, 1971; Giroux et al., 1988; Quiceno, 2003) who can add to the construction of knowledge. Said knowledge should respond to daily local community experiences and concerns. Contextualization allows us to rethink EFL materials from alternative ways of conceiving and representing the world vis-a-vis the dimensions of being, knowledge, and power. In this train of thought, the study unveils criteria inspired by the decolonial turn and grounded on critical interculturality as an alternative to guide the development of EFL materials otherwise. These criteria defy the pervasive decontextualization of standardised EFL materials, allow English teachers to resist mainstream materials development, and endorse teachers’ agency for knowledge construction.

The origins of this research trace back to several studies. Current research on EFL textbooks proves latent tensions and tendencies in national and international scenarios. A review of related studies (Núñez-Pardo, 2018a) revealed that textbooks present asymmetrical and hierarchised cultures with the predominance of Anglo-Saxon ones and the absence of experiential culture (Nguyen, 2015). Textbooks also show the prevalence of superficial culture at the expense of deep culture (Gómez, 2015), Eurocentric knowledge in detriment of local one (Aicega, 2007), stereotyped gender representations (Lee, 2014), and children as passive subjects without titularity of their rights (Herrera, 2012). Finally, literacy is regarded as a localised socio-cultural practice (Zhang, 2017). Nonetheless, research analysing EFL textbooks from a critical interculturality perspective is scarce and continues to incite tensions and controversy.

The current study also emerged from the author’s experience as a materials developer and teacher educator and researcher. As an EFL materials developer working for the local publishing industry for more than a decade, she has contributed to the production of commercial and standardised EFL textbooks. As a teacher educator and researcher, she has oriented in-service EFL teachers in their postgraduate studies; she has also contributed to the development of otherwise institutional materials that respond to the local realities of their contexts of use and production.

This study problematised the coloniality of being, coloniality of knowledge, and coloniality of power in EFL textbooks. Coloniality of being denotes the construction or image of the cultural Other (Maldonado-Torres, 2008; Quijano, 2000; Walsh, 2010). Coloniality of knowledge regards European epistemes as the absolute origin of knowledge, disregarding and marginalising other forms of knowledges (Restrepo-Rojas 2010; Walsh, 2010). Coloniality of power is rooted in capitalist globalisation and materialised in multinational organisations (Quijano, 2014; Quijano & Wallerstein, 1992) that subordinate the individuals of the periphery (Castro-Gómez, 2007). Then, how do these sorts of coloniality permeate the textbooks in question?

First, textbooks are sub-alternation instruments with the preponderance of the hegemonic ideology of the native speaker (Faez, 2011; Kumaravadivelu, 2014; Viáfara, 2016). It shows teachers as consumers of knowledge without voice and action, thus indicating coloniality of being. Second, textbooks promote language instrumentalisation, decontextualised cultural content, and uncritical use of foreign methodologies (Canagarajah, 2005; Kumaravadivelu, 2014; Núñez-Pardo, 2020a; Phillipson, 2008). As ratified by Soto-Molina and Méndez’s (2020) documentary analysis, the content of textbooks deals with “high levels of alienation burden, superficial cultural components and instrumentation to the submissive person who favours the dominant culture of English and does not offer possibilities to embrace interculturality in ELF teaching contexts” (p. 11). This converts teachers into technicians and reproducers of Eurocentric knowledge, demonstrating coloniality of knowledge. Third, the imperialism of a commercially oriented publishing industry is supported by a bilingual policy that associates English with work, productivity, globalisation, and neoliberalism (González, 2012; Guerrero-Nieto & Quintero-Polo, 2021; Miranda & Valencia-Giraldo, 2019; Usma, 2009a). This condition makes teachers competitive and oppressed actors, suggesting coloniality of power. In short, the content of EFL textbooks replicates and perpetuates ways of being, knowing, and exerting power that conceal, subdue, or misrepresent the plurality of socio-cultural realities of local contexts. Hence, EFL textbooks play a key role in disseminating colonialist and neoliberal agendas that omit or distort societal differences.

This documentary research was guided by the main research question: What ontological, epistemological, and power criteria grounded on critical interculturality as a decolonial alternative orient the development of the English textbook to overcome its decontextualisation from the voices of local authors, teachers, and editors? The analysis was also led by the following three subsidiary research questions: (a) What traces of coloniality are observed in the content of readings, their iconography, and learning activities proposed in the most utilised English textbooks in the Colombian context during the period 2004-2016? (b) What possible transformations have been experienced by the content of readings, their iconography, and learning activities proposed in the most utilised English textbooks in the Colombian context during the period 2004-2016?

Theoretical Foundations

School textbooks have played a central role in language teaching and learning throughout history. These also have offered a prolific field for analysing their philosophical dimension ( Grupo Eleuterio Quintanilla, 1996). In this light, textbooks deserve critical examination to challenge their industrial development and thus encourage teachers and students to fight globally distributed biases. In doing so, research on textbooks comprises their evaluation and analysis. The former focuses on accurately determining whether a set of parameters is fulfilled or not in textbooks to recommend alternatives for their improvement (Littlejohn, 2012). This process can be done before, during, or after their use. In turn, analysis of textbooks centres on recognising latent messages present in their content to make inductive inferences (Krippendorff, 2004), within a socio-cultural, geographic, and historic context. This study opted for the critical content analysis of textbooks to uncover their decontextualisation and propose disruptive ways of developing EFL materials.

Concerning the theoretical foundations of the study, school textbooks conceived as geographically, historically, culturally, and politically situated artefacts (Choppin, 2001; Escolano, 2012) were explored. Second, textbooks were also viewed as ideological resources that create stereotypes and disseminate North and Western cultures (Apple, 1992). Third, textbooks were understood as tools for curricular support (Moya, 2008). Fourth, they were considered commercial and profitable products (Martínez, 2008). All in all, these views substantiate the fact that textbooks are fruitful objects of study prone to be further explored to contest their decontextualisation, uniformity, and marketisation.

EFL textbooks, which were born in the 1830s (Borre, 1996), have been conceptualised in four main categories. These are indispensable artefacts for the teaching of English (Davcheva & Sercu, 2005). Moreover, they are also socio-cultural mediators shaped by the changes in zeitgeist (Littlejohn, 2012; Rico, 2012). Furthermore, EFL textbooks are propagators of racial, gender, and class colonial bias and knowledge-based ideologies (Granda, 2004; Gray, 2013; Núñez-Pardo, 2018a). Finally, they are mediations whose socio-cultural, pedagogical, didactic, and cognitive nature fosters both teaching and learning processes and teachers’ and students’ critical social and political awareness and transformation. The foregoing categories offer a look at the range of connotations EFL textbooks encompass and inform this study regarding their adaptability, complexity, and bias. Likewise, they ratify the need to critically analyse these artefacts in search of their contextualisation and, thus, their decolonisation. Having discussed EFL textbooks as the first theoretical foundation of this research, their relation to critical interculturality is argued next.

Critical interculturality is a decolonial alternative that contributes to negotiating socio-cultural diversity and the conciliation of the difference between the local and the foreign (Walsh, 2010; Tubino, 2005). It aims at tracing European colonialism to stop perpetuating and naturalising subordinated socio-cultural relations. In this vein, critical interculturality contests Eurocentric visions of knowledge and the imperialism of the commercial publishing industry of textbooks since they conceal and misrepresent the multiplicity of socio-cultural realities of local contexts. The decolonial turn, as a shift in knowledge construction (Maldonado-Torres, 2008) implying epistemic diversity (Grosfoguel, 2007), impels “emancipating critical thinking, reducing Eurocentric-knowledge dependence, and resisting the supremacy of political and socio-economic agendas that legitimate the interests of the dominant social order” (Núñez-Pardo, 2018b, p. 3). Accordingly, critical interculturality and the decolonial turns advocate for more symmetric and diverse sociocultural representations and relationships in EFL materials, enabling individuals’ critical socio-cultural and political awareness, transformation, and construction of local knowledge.

Method

This documentary research comprehended EFL textbooks as objects of study and aimed to critically scrutinise them based on their socio-cultural context through the qualitative content analysis method. This is because such content analysis seeks to understand the hidden messages present in written texts (Krippendorff, 2004). Likewise, this choice was made since, in this avant-garde framework of empirical approximation, quantification is not a definite criterion to analyse content (Krippendorff, 2004). All in all, the critical content analysis proposed departed from the qualitative nature of texts and privileged verbal and descriptive procedures that separate it from a quantifying perspective.

By the same token, the study was framed within the qualitative approach as it fostered the emergence of alternative epistemologies from subaltern subjects and loci. It also rescued subjectivity to make sense of complex human phenomena in social interaction (Sandoval, 1996). Furthermore, the socio-critical paradigm informed this research. This paradigm reclaims subjectivities understood as individuals’ perceptions, opinions, arguments, and discourses, which in interaction with others, lead the researcher to acknowledge the social construction of knowledge. In this vein, this paradigm paved the path for this study to advocate interpretation and emancipation to make sense of reality (Kincheloe & McLaren, 2005).

Regarding methodological strategies, the unit of analysis was English textbooks. Six EFL textbooks made up the sampling unit; the paragraph was the recording unit; 86 passages and their reading comprehension activities and accompanying iconography constituted the unit of context. Additionally, comprehension matrices for interpretation and critical analysis of the content of readings were designed.

Besides, since qualitative content analysts contemplate the voices of readers, critics, and users of the texts (Krippendorff, 2004), the perceptions of Colombian English teachers, authors, and editors were brought up to enrich the analysis. Thus, they used these textbooks in their English classes in secondary state-funded schools, authored them, or performed the role of editors in both a local and a foreign publishing house. Their insights were gathered through a focus group with six Colombian English teachers and in-depth interviews with four Colombian authors and two editors; all of them signed the informed consent to participate in the study. For the focus group, the participant teachers expressed themselves freely without much intervention from the moderator since the interest was to collect as much information as possible. Likewise, the qualitative and dialogic nature of in-depth interviews allowed for building the experience of the participants authors and editors in a horizontal relationship (Robles, 2011). These genuine encounters granted a conjoint construction of the meaning participants attributed to the cultural content of readings, comprehension activities, and accompanying iconography, in tandem with the researcher’s interpretation. Finally, theory triangulation was employed, confronting the emergent categories with existing theory.

Findings

The findings below are presented in relation to the research questions posed. The first question addressed the formulation of a set of criteria to disrupt the coloniality found in the EFL textbooks.

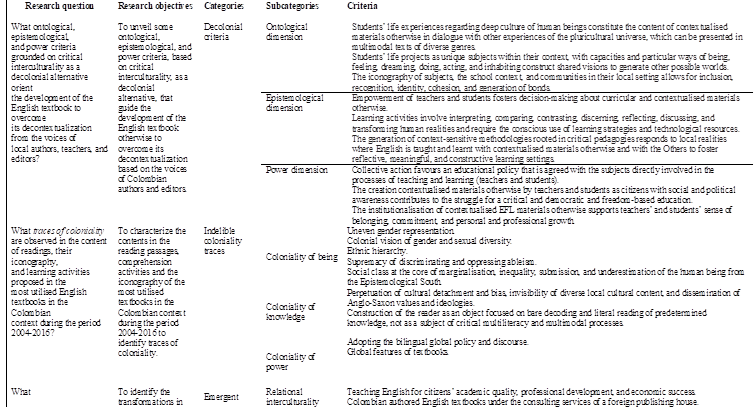

The critical analysis revealed three triads of decolonial criteria that respond the main research question of this study (see the Introduction). They stemmed from the perspective of critical interculturality as a pedagogical alternative to unsettle the current representations in EFL textbooks that were found during the process of analysing their content. The subsidiary questions aimed at identifying those current representations in EFL textbooks that are still engaged in colonial views, and also to observe whether there were elements of decoloniality in the textbooks analysed. Therefore, the categories of indelible coloniality traces and emergent decoloniality signs in EFL textbooks answered these questions (Table 1).

Tabla 1:

Research Categories (Cont.)

[i]*These criteria were the result of a study entitled "Decolonizar el libro de texto de inglés: una apuesta desde la interculturalidad crítica" (Núñez-Pardo, 2020b), carried out wihtin the doctoral programme in Sciences of Education at Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia (UPTC).

The three triads of decolonial criteria emerged from the researcher’s interpretation and analysis of the meaning that Colombian teachers, authors, and editors attribute to the dimensions of being, knowledge, and power present in the textbooks they use, write, or edit. Thus, the nine criteria derived from the data obtained from the voices of the participants and the author’s experience as a materials developer and teacher educator who mentors in-service EFL teachers’ pedagogical interventions for their studies.

Decolonial Criteria

The ontological criteria challenge the hegemonic reproduction of beliefs, behaviours, values, and ideologies. In doing so, there exist three possibilities. First, there is a need for developing EFL materials that advocate for an ethical, political, and community project of social transformation in vulnerable local contexts in which English is learnt and taught with these socio-cultural mediations. This entails ridding them off the idealised aspirational context commonly shown in global textbooks. Second, generating reflection spaces for the construction of students’ life projects could boost assertive decision-making related to their future positioning in society and contributes to emancipatory education. Third, it is important to provide EFL materials as mediations that regard iconographic representation of subjects in their local context through constant dialogue with the pluricultural universe. This is because iconography in EFL materials takes part in the visual and spatial design of texts, supporting their attributes of being coherent, understandable, and corresponding (Levin & Mayer, 1993).

The epistemological criteria disrupt futile content and hegemonic cultural representations of a peaceful world, fostering the construction of knowledge from and out of our vulnerable local communities. Three procedures could be implemented. The first one is to cast doubt on decontextualisation of knowledge. This is because it restrains the recovery of ancestral knowledge and obstructs the construction of local knowledge (Canagarajah, 2002; Giroux et al., 1988; Kumaravadivelu, 2014; Núñez-Pardo, 2020a, 2021), widening the gap between school, home, and community. In this vein, teachers need to articulate students’ knowledge of their context in school curricula, materials, and pedagogical practices. Thus, reclaiming and positioning teachers and students as curriculum and materials producers generate discerning, meaningful, and transformative learning environments. Second, to unsettle the uncritical tradition that prevents students to think critically (Giroux, 2014), EFL materials need to include thought-provoking activities that cultivate students’ critical thinking (Facione, 2011) and lead to alternatives that solve community problems. Third, hegemonic knowledge ought to be overcome through historic, geographic, political, and socio-cultural thought of the voiceless in periphery countries. For instance, critical pedagogies, which are emanated from social radical thinking and students’ and teachers’ experiential culture, challenge banking and oppressive education and disturb the reproduction and naturalisation of hegemonic materials and methodologies. Thereby, EFL materials development should be based on context-bound pedagogies (Apple, 2004; Kumaravadivelu, 2014; Núñez-Pardo, 2020a, 2020b; Núñez-Pardo & Téllez-Téllez, 2021), fostering situated and constructive learning settings in search of cultural changes in local realities.

The power criteria contest the tendency of bilingualism policy to legitimise imperative global and neoliberal circulating discourses through standardised English varieties, teaching approaches, materials, testing, and training programmes (Block, 2017; Núñez-Pardo, 2020a; Phillipson, 2008, 2016; Usma, 2009a). In Colombia, the top-down bilingualism policy renders disparities (Cruz-Arcila, 2017; Usma, 2009b) and broadens the gap between the powerful and the powerless (Guerrero, 2008). Therefore, it is crucial to take three actions. First, educational initiatives should endorse a bottom-up approach to bilingual education policy (Levinson et al., 2009) that relies on the expertise of local teachers (Shohamy, 2009) and fosters the appropriation of a context-responsive policy. Second, emancipatory education ought to ask teachers and students to critically ponder, interpret, and interrogate their multifaceted individual subjectivities and the world around them. Third, to institutionalise contextualised and decolonised EFL materials otherwise, they should be culturally situated. At its core, contextualisation “destabilises mainstream ways of developing standardised, homogenised, decontextualised and meaningless materials” (Núñez-Pardo, 2019, p. 19). Accordingly, the localisation of EFL materials otherwise fosters students’ free decision-making and recreation of their realities in search of a dignified and egalitarian life.

The aforementioned criteria aim to guide the construction of contextualised and decolonised EFL materials otherwise. To defy bias in global EFL textbooks and avoid introducing a local one, these decolonial criteria entail that critical interculturality seeks a dialogical relationship between received hegemonic knowledges and local knowledge.

The criteria draw on the cultural circuit (Du Gay et al., 1997) that is consistent with the colonialities of EFL textbooks as their cultural representations shape students’ and teachers’ construction of individual and collective identity. These representations are incorporated into the industrial production of global textbooks since, as claimed by Phillipson (2008), this production serves a worldwide linguistic market of a dominant language. Thence, EFL textbooks become consumption goods with exchange and use values related to an instrumental and hegemonic operationalisation of the ministerial regulation, encouraging economic interests of the editorial industry (Usma, 2009b). This consumption is backed by ideological agendas of governments whose goal is to increase the dissemination of ideas (Gray, 2013) and consolidate EFL education as a profitable market. The criteria also build on Kumaravadivelu’s (2003) post-method parameters of particularity (being sensitive to students and teachers’ socio-cultural context), practicality (building theory through practice), and possibility (recognising students’ and teachers’ subjectivities).

This unsettling endeavour stems from a local initiative that deems English teachers as critical political subjects of knowledge and culture. In other words, teachers can use their voice and agency to transform their harsh realities in search of democratic education (Freire, 1971; Núñez-Pardo, 2020a). This initiative also conceives materials development as a reflective, theoretical, culturally and politically situated, and transformative undertaking carried out by teachers otherwise1 who produce their materials in association with students otherwise in local contexts. The outcomes of such a defiant process are contextualised, desirable, decolonised EFL materials otherwise aimed at educating political subjects who are critically aware of their own culture and others’ and develop an understanding of cultural diversity. This implies a critical approach to developing EFL materials that considers the particularities of the rural and urban school, home, and community contexts, as spaces for the social construction of knowledge.

Having discussed the criteria, the next section presents the remaining categories of analysis that respond the subsidiary research questions.

Indelible Coloniality Traces

This category analyses the coloniality traces found in the textbooks, as posed in the first subsidiary research question. It encompasses three subcategories coloniality of being, coloniality of knowledge, and coloniality of power that are addressed respectively as follows. The first subcategory is evident in traditional representations of identity markers in content and iconography. It stereotypes and discriminates homogenising and concealing individual differences and maintaining asymmetry in human relations. Within it, five recurrent patterns were identified.

The first pattern comprises uneven gender representations with the predominance of male images (Guijarro, 2005; Porreca, 1984) as observed in the iconography and content of readings. However, regarding the iconographic aspect, teachers, authors, and editors asserted there is gender balance. Besides repeatedly referring to graphic gender evenness, they also mentioned the Williams sisters as female representations of leadership, which could result alien to the local users of these textbooks as they do not consider women from local contexts. This incongruent aspect is shown in the excerpts below2.

There is gender balance, the use of iconography shows people of ages, including children, adult women and men and mostly students (FG - T3). There is a news report that describes the entire sports career of the Williams sisters who are professional tennis players and who are also of colour; they are black American (FG - A2). We try to keep a graphic gender balance; we search for a balance of female and male genders […] For instance, the Williams sisters appeared in one of the books (II - E1)

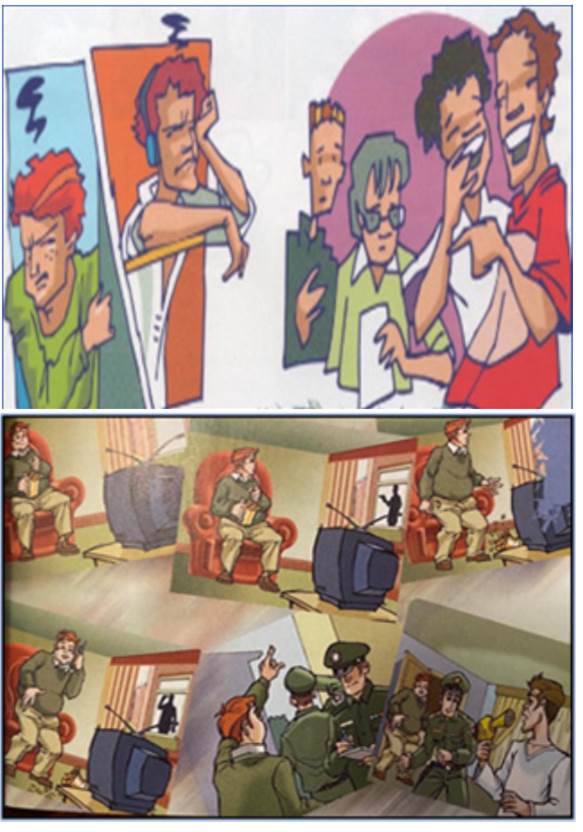

As opposed to what the participants expressed, the iconographic representation of readings mostly includes males of all ages as exemplified in the illustrations in Figure 1.

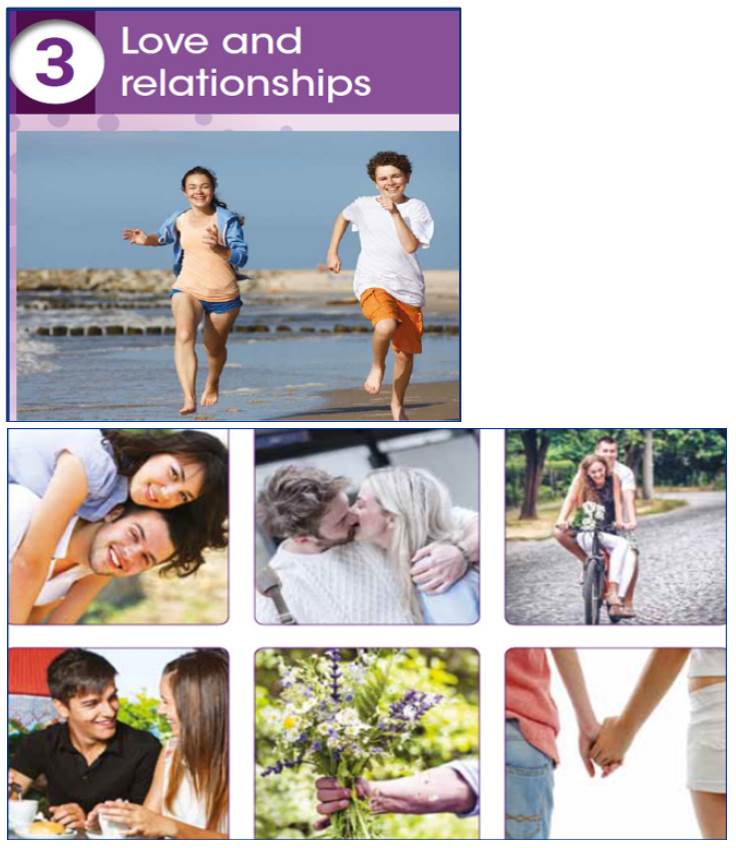

The second pattern shows the prevalence of a colonial binary vision of gender and sexual diversity that imposes heteronormativity. No procreative sex is stigmatised; emotions and human bodies are regulated, naturalising the colonial sexual difference that hides and condemns the diversity of sexual practices and orientations as they are deemed abject (Domínguez, 2016). This perpetuates the stigma of sexuality. The Other is condemned because they do not fit reductionist binary standards, as though there was not a considerable LGTBQ+ community in our local context and our country in general. Teachers, authors, and editors corroborated that non-traditional sexual orientation is regarded as taboo. Thus, EFL textbooks examined evade these topics since they also target religious schools, where these themes generate resistance, according to what one of the editors expresses in the in-depth interview. This reductionist vision of gender and sexual orientation can be seen in these extracts:

The books do not show contemporary families made up of two men or two women as a parental nucleus (FG - T4). In one of the readings, a homosexuality issue is presented in a superficial way. (FG - T2).

Sexual orientations are taboo, so we avoid them […] Editors sustained that these textbooks are addressed to religious schools where these themes are not well received (FG - A4).

Authors included themes on sexual diversity; however, officials from the men asked us to withdraw content on sexual diversity because it could generate some sort of resistance from users [school communities that use the textbooks]. Including it would be like taking our own product off the market ourselves (II - E1).

In addition, the pictographic representation in readings maintains heterosexuality as the photographs in Figure 2 demonstrate.

Figure 2

Colonial Vision of Gender and Sexual Diversity

Source: English, Please, 1, module 3 (pp. 84, 102).

The third pattern indicates the dominance of White population and ethnic hierarchy based on phenotype that governs the identity construction of those without European standards (Fanon, 1986; Marín, 2003; Mbembe, 2017). This supremacy exists because race is a socio-cultural construct resulting from naturalising and perpetuating historic, religious, and biological discriminating discourses that stigmatise and make ethnic diversity invisible. Since human beings share a common origin, biological races do not exist; then, they belong to the same genetic repertoire. Nonetheless, the analysed textbooks promote a racial construction of identity in which white ethnicity is ideal and thus, it is not questioned. Teachers, authors, and editors ratified the inclusion of people that fit the White American or European dominant cultural standards. Authors and editors also mentioned that publishing houses resort to stereotyped iconography offered by expensive image banks that present a hierarchy of models with an idealised physical appearance of White people for diverse societies. The excerpts below describe this:

There is no reference to the indigenous race. Instead, we see people with the standard of European countries or from the United States that are far away from our students’ reality (FG - T2).

Almost everything in this textbook is American or British. It is quite linked to the editorial directions based on an available bank of images (FG - A2).

In general, images are very expensive; we use an American bank of images that are already stereotyped and hierarchised based on models of ideal aspect (II - E1).

The Black people included are famous, wealthy, successful, or emblematic figures; for instance, Will Smith and the Williams sisters, Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela, and the like. The iconography displays people of privilege who do not experience the same racialisation as others may, as observed in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Ethnic Hierarchy

Source: (Left) Teenagers New Generation 10 (p. 59). (Right) Viewpoints 10 (pp. 14, 15, 40, 41).

The fourth pattern entails the supremacy of discriminating and oppressing ableism that conceals people with disabilities, maintaining the binary category abled-disabled (Asch, 2001; Bogart & Dunn, 2019; Hahn, 1988). It is imperative to understand that context is what handicaps people, not the physical, cognitive, or mental variation they experience. Teachers, authors, and editors affirmed that the representation of diverse capacities is completely absent in the readings of the EFL textbooks they use. They also admitted that people with diverse capacities and their realities should be included. Ableism predominance can be observed in the following fragments:

These types of aspects are not represented in any of the book units (FG - T5). In this book, one would not find people using crutches or a wheelchair; honestly, this population should be included, but they are not in these books (FG - A2). Here we try to make it appear, although it does not really appear to the extent to which we would have liked (II - E2

Likewise, the graphic representation of the readings maintains the binary category abled-disabled. The photographs show abled-bodied people that are healthy and strong like football players or cyclists, as portrayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Supremacy of Ableism

Source: (Left) Teenagers New Generation 10 (p. 30). (Right) Teenagers New Generation 11 (p. 73).

The fifth pattern reveals that social class constitutes the core of marginalisation, inequality, submission, and underestimation of the human being from the Epistemological South (Santos, 2014; Fanon, 1986; Van Dijk, 1994). Teachers, authors, and editors contended that there are no explicit references to social class in the textbooks. Instead, they said that these show well-off people practicing sophisticated sports that are not compatible with the experiences of the text users in the Colombian school communities. They also asserted that the content of these materials alludes to people with economic means to afford luxuries, which is quite distant from the purchasing power of local users in Colombia’s state-funded schools. These extracts account for this situation:

Exceptionally, this book presents the prototype of an African, but that person is not a common individual; on the contrary, the character represents someone successful and wealthy (FG - T1).

In this textbook, you will never see a poor person, or someone begging or asking for help in the streets. Instead, you will see people practicing horse riding, skiing, surfing, or rock climbing, which are not congruent with the students’ realities (FG - A2).

Additionally, the iconography of the readings portrays this incongruent feature (see Figure 5).

Figure 5

Representation of Upper Social Classes

Source: (Left) Teenagers New Generation 10 (p. 30). (Right): Teenagers New Generation 11 (pp. 65, 70).

The second subcategory (coloniality of knowledge) involves the persistence of intellectual, cognitive, and cultural European colonialism, cultural hegemony, and replication of Western and Northern predominant knowledge. This colonialism favours an aspirational view of a visible, admiring, and uniform culture. Three recurring patterns were recognised.

The first pattern refers to the perpetuation of cultural detachment and bias, the invisibility of diverse local cultural content, and the dissemination of Anglo-Saxon values and ideologies (Dussel, 2007; Fanon, 1986; Granados-Beltrán, 2016; Núñez-Pardo, 2020b; Said, 1993; Phillipson, 2016). This means that cultural content and competence are based on hegemonic Western and Northern countries and their model of acculturation through the reproduction of Eurocentric knowledge as the unique source. As a result, ancestral knowledge like círculos de palabra [circles of words], arrullos [rocking babies], alabaos [dead praising], and partear [birthing] from the Colombian Pacific region seem unknown, exotic, and even magical to our population despite sharing the same territory. While teachers and authors remarked on topics from the North American, British, and Canadian stereotypical cultures, editors highlighted topics about Peru, Mexico, and Brazil due to their market impact. A salient feature is the absence of references to Colombia in both the readings and iconography. The subsequent excerpts depict biased cultural representations:

Most of the topics are about foreign cultures: The Canadian, English, and North American cultures (FG - T3).

Besides the North American and British cultures, the Canadian culture is also represented (FG - A1).

Cultural content is an issue subject to the conditions and orientations that we, as authors, receive from the publishing house (FG -A2).

English teachers ask for textbooks that show students other world visions; for this reason, the local begins to prevail with content related to Peru, Mexico, and Brazil. It also responds to a market share (II - E2).

Decontextualised cultural content is mirrored in the iconography in Figure 6.

Figure 6

Dissemination of Anglo-Saxon Values and Ideologies

Source: Teenagers New Generation 9 (pp. 58, 59)

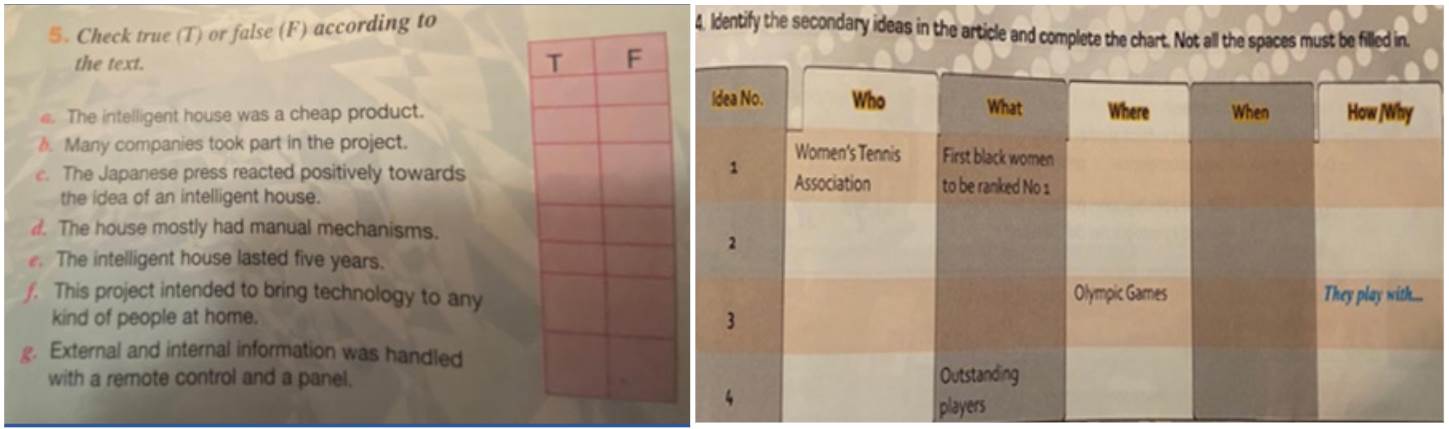

The second pattern encompasses the construction of the reader as an object (i.e., someone focused on bare decoding and literal reading of predetermined knowledge), not as a subject of critical multiliteracy and multimodal processes. Uncritical reading results from privileging descriptive or narrative texts that promote literal and intensive reading that leads to grammatical work. Plain decoding also derives from the reproduction of bottom-up and top-down reading comprehension approaches used in isolation and the omission of critical thinking-oriented activities, which hinders the possibility to develop high-order thinking skills (Apple, 2004; Canagarajah, 2002; Giroux et al., 1988; Gray, 2013; Kumaravadivelu, 2014; Rico, 2012). On the contrary, critical literacy processes should centre on textuality (attributes that make a text coherent and cohesive), intertextuality (the relationship with other texts produced previously), and sub-textuality (reading below the surface of words to recognise latent or hidden messages of the text) (Pennycook, 2001). These processes also raise critical multiliterate and multimodal readers that assume a critical stance on the text and value the multiple cultural differences (Álvarez-Valencia, 2016; Cassany & Castellà, 2010; Freire & Macedo, 1987; New London Group, 1996).

The textbooks analysed do not promote critical literacy practices or draw on multiliterate and multimodal texts since they do not transcend word comprehension in narrative texts. Teachers, authors, and editors sustained that these materials privilege narrative texts that neither foster controversy nor promote an association with students’ experiences to generate debate or construction of arguments. The fragments below evince that reading comprehension activities proposed in the textbooks do not promote critical reading:

Texts are rather descriptive and expositive; they do not generate controversial situations (FG -T1).

Comprehension activities are literal so the answers are there; activities that generate debate are absent. Reading comprehension does not promote interpretation nor critical reading (FG - T3).

Very rarely we invite students to reflect or to go beyond the text. Reading comprehension activities are linked to textual content. Readings do not offer students the possibility to connect with their own experience or to assume a critical stance on the text (FG - A2).

Reading comprehension activities aim at recycling, reviewing, or reinforcing linguistic contents. The grammatical component is very strong because the marketing department informed us that teachers want to have more grammar in the textbooks […] Unfortunately, narrative and descriptive texts prevail, and critical thinking is hardly present (II - E2).

Similar reading comprehension activities boost literal reading as observed in the samples shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7

Literacy Focused on Bare Decoding and Literal Reading

Source: (Left) Teenagers New Generation10 (p.44). (Right) Viewpoints 5 (p.15).

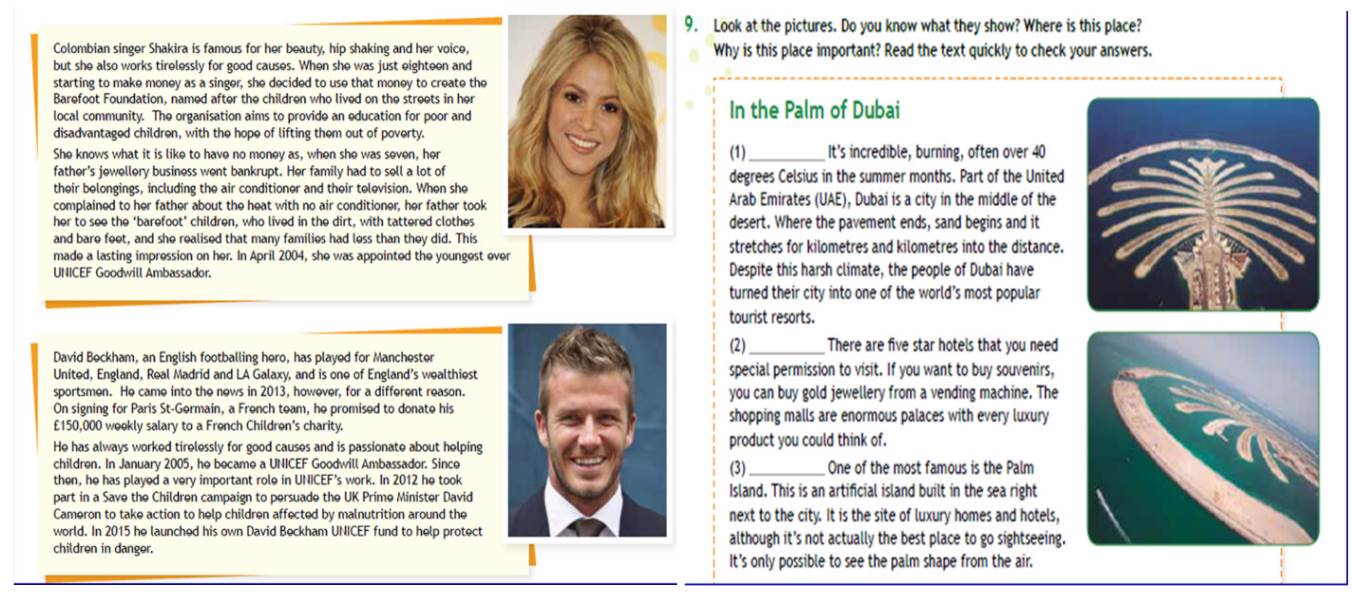

The third subcategory (coloniality of power) contains modern Eurocentrism i.e., world power controls the human life experience in all its dimensions of civilization (Walsh, 2007) and enslaves human beings to consumerism at a global level (Bauman, 2007; Giddens, 2018;). Two interrelated patterns were recognised. The first pattern comprises adopting a bilingual global policy and discourse that focuses only on the learning of English for the sake of economic competitiveness, neglecting other languages (González, 2009; Guerrero, 2008; Usma, 2015), which perpetuates the knowledge-based economy (Fairclough, 2006). The second pattern tackles the global text features and promotes individualistic productivity, entrepreneurial skills, and economic success as the pillars of pervasive phenomena such as capitalism, globalisation, and neoliberalism. These conditions enslave human beings to consumerism on a global scale, precluding cultural, social, and pedagogical values, and regularising misery and injustice (Bauman, 2007; Block, 2017; Kubota & Lin, 2006; Ulum & Köksal, 2019). Teachers and authors manifested that references to North American celebrities, the ideal family, and successful young people constitute not only an untrue dream for our students in their local contexts but also a detached referent that associates the learning of English to wealthiness, affordability and luxury. Editors acknowledged that the profitable interest of publishing houses responds to globalisation, the hegemony of the Northern and Western cultures, obstructions imposed by publishing conglomerates, the users of the textbooks, the bank of images, and the editor. The next excerpts illustrate the previous aspects:

The book includes a reading about Shakira as an international celebrity and as a model to follow. It also includes famous personalities like Jennifer Lopez, Nicole Kidman, and Brad Pitt (FG - T2).

In this textbook, the perfect family, the happy person, successful young people prevail, far from the local reality […] The topics include tourism, technology, fictional literature (FG - A2).

Topics like planning a holiday involve selecting the country, requirements to fulfil before travelling, and the budget (FG - A4).

Editorial production is subject to a market logic and it responds to the global market. Unfortunately, the hegemony of the North American culture […] We look for global referents (II - E1).

There are obstacles imposed by the company, the public, the banks of images, and the editors (II - E2).

The samples in Figure 8 corroborate the previously mentioned conditions.

Emergent Decoloniality Signs

Emergent decoloniality signs in EFL textbooks constitute the second category that responds to the second subsidiary question. This question concerns possible transformations of EFL textbooks content and holds a sole subcategory labelled relational interculturality. It is important to note that this sort of interculturality has remained in a basic form of exchange among cultures in conditions of inequality, without referring to its causes or the purposes of social struggle for equal rights and opportunities (Tubino, 2005; Walsh, 2010). The analysis revealed two associated decoloniality patterns. First, the regulation pattern since one of the textbooks analysed responds to the country’s bilingual policy of teaching English for citizens’ academic quality and professional development oriented towards productivity, profitability, globalisation, and neoliberalism. Second, the pattern of having Colombian-authored English textbooks is evident, it is reliant on consulting services from a foreign publishing house, though. Despite being locally developed, decoloniality is recognised in the topics included in these textbooks. Out of 86 readings, only six passages address adolescents’ emotions and concerns regarding engagement, future careers, a gay couple, bullying, school sexism, child labour, and environmental care. Although the readings indicate changes vis-a-vis traditional content, all of them are descriptive texts followed by literal comprehension activities that preclude reflection, debate, and critical thinking as displayed in the next extracts:

In addition to narrative texts that unsettle conventional content but normalise mere decoding, iconography and reading passages evidence the foregoing emergent change in textbooks (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Teaching English for citizens’ academic quality, professional development, and economic success

Source: English, Please! 11, module 3, unit 1, lesson 1 (p. 91)

The former results offer tangible possibilities for teachers to contest colonialised EFL textbooks and take counter-hegemonic actions, which demands critical socio-cultural and political consciousness and discourse in both students and teachers. It also endorses actions in favour of democratic transformation of EFL curricula, materials, teaching, language policy, and assessment practices. After arguing the findings, the next section presents the conclusions drawn from the study.

Conclusions

This qualitative documentary research unveiled three triads of decolonial criteria: a triad of ontological criteria, a triad of epistemological criteria and a triad of power criteria. They emerged to orient the creation of desirable EFL materials otherwise, as summarised in Table 1. The critical analysis also revealed colonial representations of gender, races, sexual orientations, capacities, and social classes in EFL textbooks, as well as references to an essentialist and static vision of culture. Also, emerging signs of decoloniality were evinced in response to the Colombian bilingual policy of teaching English for citizens’ academic excellence and professional growth.

Research on EFL materials needs to reach beyond traditional evaluation, analysing their content critically. This article argued against EFL textbooks’ ontological, epistemological, and power hegemony. It also questioned the adoption of a global policy and discourse in EFL textbooks that relates English to individualistic efficiency, entrepreneurial skills, and economic progress. These power forces control EFL curricula, materials, cultural content, standardised English varieties, and teaching and assessment practices replicated and naturalised in global EFL textbooks, which makes it tough to defy them. Although globalised and neoliberal discourses circulate the ideals of freedom and growth, these practices reduce teachers and students to consuming knowledge instead of producing it.

The results of the critical analysis of textbooks’ content reported here uncovered the need for rethinking EFL materials from a critical interculturality stance. It is then, time to resist and disrupt a series of colonial binaries (e.g., White-Non-White) that imply a so-called biological superiority among human beings, ranking them from savages to Europeans. Critical interculturality also demands unsettling the colonial sexual difference that perpetuates and naturalises Eurocentric Judeo-Christian categories on sex and gender, maintaining heteronormativity. Likewise, it urges to challenge the abled-disabled binary that has been made up by a medicalised notion of the normal body and supported by a pattern of normative beauty, paving the way for the reproduction of capitalist values. Similarly, Western and Northern dominant knowledge and homogeneous culture should be withstood. This is because they nurture an essentialist view of a static culture that conceals evolving cultural practices, hindering the possibility to build cultural and critical intercultural awareness. Finally, adopting the globalised discourse in language policy and EFL textbooks reduces the human experience to rampant consumption, preserving asymmetrical relations between hegemonic and periphery communities.

Creating EFL materials from a decolonial perspective compels teachers to become more critical of EFL materials content, learning activities and strategies, underpinning language pedagogies, iconography, language policy, and assessment practices. This reflective, localised, theoretical, and applicable endeavour allows them to ponder, question, re-signify, and transform their pedagogical praxis as they exert agency to contest hegemony in EFL materials. As a result, teachers empower themselves to recreate situated EFL education practices.

Some limitations of this research comprised: an analysis centred on the content of the reading lessons, not on complete textbooks; not all the authors and editors agreed to participate in the study; and some of them insisted on answering the questions regarding the whole textbook.