Introduction

In the last few years, mainly with the advent of video-on-demand streaming platforms, audiovisual productions seem to travel easier and faster. Many productions are released on the same dates worldwide, thus enhancing the importance of media localisation nowadays. Spanish series, for instance, are becoming increasingly popular; La casa de papel (Money Heist, A. Pina, 2017-2021), Las chicas del cable [Cable Girls] (R. Campos et al., 2017-2020), and Élite (Montero & Madrona, 2018-present) are just a few examples that showcase the reception of Spanish TV series among international audiences, and how Spanish fiction series are settling in abroad (Diego & Grandio, 2018). According to Filmarket Hub (2020), the success of Spanish TV series worldwide is due to factors such as Spanish being the fourth most spoken language in the world in terms of the number of speakers (EFSA, 2020), the use of recognisable stories, and their ability to respond to the target audience’s demands. Despite the design of this new type of Spanish series, the original culture is always present in their scripts, especially in those genres in which cultural allusions are used for depicting the daily life of a social group.

Series constitute a great means for the dissemination of culture. In this respect, Ranzato (2016, p. 3) points out that the transfer of cultural references into other languages and cultures “is particularly relevant in the case of fiction television texts as this kind of audiovisual programme usually contains a great number of cultural elements”. She states that these “culturally embedded references” (Ranzato, 2016, p. 104) are not always used to attain the same effects in audiovisual texts although some shows use a considerable number of elements specific to the original culture to produce humour and jokes. In this sense, Chiaro (1992, pp. 5-10) suggests that jokes do not always travel well from one culture to another; as confirmed by other scholars more recently (Pedersen, 2011; Ranzato, 2013). On the contrary, studies focusing on the translation of jokes in sitcoms such as Friends (Ranzato, 2016) and Veep (Ogea Pozo, 2021) prove that the effect of having viewers enjoy the programme and have fun while following the plot in translation may be better achieved with target-oriented solutions.

This article aims to analyse instances of humour based on stereotypes and cultural references in a Spanish TV series recently dubbed into English by Netflix. An empirical study on the perception of a dubbed Spanish comedy by English-speaking viewers is presented to establish whether, and if so how, culture-bound humour travels and how translation can foster this cultural exchange. To this end, a selection of video excerpts from the first season of the Spanish comedy Valeria was collated. These passages were considered to be highly representative of Spanish popular culture and, in most cases, used to pursue a humorous effect that would be easily identifiable by native Spaniards of any age range. The same excerpts were taken from the English-dubbed version for the experiment. Participants were undergraduate students enrolled in a bachelor’s programme in modern foreign languages at a uk higher education institution. The responses and feedback obtained were analysed to determine how a sample of native English-speaking participants perceive Spanish cultural elements in media productions, how they interpret the given translation in terms of cultural and humorous transference, and whether they would prefer a different option, based on either a source-oriented or a target-oriented translation strategy, for an English-speaking audience.

Theoretical Framework

This section will delve into previous studies that sustain the theoretical basis for the empirical approach that has been developed. For this purpose, the discussion will focus on the latest industry trends that capitalise on English dubbing of Spanish productions as well as on culture, humour, and perception.

State of the Art: English-Language Dubbing

Traditionally, English-speaking countries have not been included by scholars on the list of so-called “dubbing countries” (Chaume, 2012, p. 6). However, as Hayes (2021, p. 1) argues, “in 2017, English dubbing entered the mainstream on the initiative of the subscription video-on-demand service (SVoD) Netflix”. Despite earlier attempts, the English dubbing mediascape has now changed dramatically; and according to Spiteri Miggiani (2021, p. 137), there is a “sudden boom” of non-English language content on streaming platforms. One of the reasons behind this increase in non-English language content is that some platforms are complying with Article 13 of the Audiovisual Media Services Directive (2018) passed by the European Union in November 2018, according to which, 30% of the content that is to be distributed in the eu needs to have been produced in Europe.

Following this mushrooming of non-English language media productions, dubbing audiovisual productions into English has become an emerging field of research. Although some authors claim that audiences tend to prefer the translation method they are accustomed to (i.e., the one they have grown up with and are best acquainted with; Nornes, 2007; Wissmath et al., 2009), the reality is that many dubbing-oriented countries are currently consuming more and more subtitles (Chaume, 2019), and subtitling-oriented countries are also experiencing a “dubbing revolution” (Moore, 2018, in Ranzato & Zanotti, 2019, p. 3) or “dubbing resurge” (Sánchez-Mompeán, 2021, p. 180). However, in countries less habituated to dubbing, viewers seem to feel a stronger “dubby effect”, which has been described as anything that is not speech-like or is conspicuously out of time with how actors’ mouths are moving onscreen (Goldsmith, 2019, in Sánchez-Mompeán, 2021, p. 185) and can break the “suspension of linguistic disbelief” (Romero-Fresco, 2009, p. 49). Since English-speaking audiences have traditionally been less exposed to dubbed content, this effect could certainly affect their perception of newly dubbed mainstream productions. Viewers from the Anglophone spheres may need some time to get used to dubbing until the “cultural discord” (Spiteri Miggiani, 2021, p. 139) is less present.

Humour and Cultural Elements

Describing humour may be tricky, since definitions and approaches have accumulated over time. According to Nash (1985), humour is an interaction between people in social situations and cultures which is normally intended to make receivers smile, laugh, or giggle, even though it may also aim to hurt by being derogative. Some humorous utterances may fail to produce laughter, not have any intent to produce it, or even provoke an invisible reaction (i.e., an emotional response such as exhilaration; Diaz-Cintas & Remael, 2021; Chiaro, 2010). Consequently, humour relies on both the language and the culture in which it originates (Santana, 2005). Based on Nash’s observation (1985), Martinez-Tejerina (2016, p. 73) suggests that “all people laugh, but not for the same reasons, nor in the same situation, nor at the same references.” Humour usually depends on factual knowledge shared among individuals and may have different meanings in different social contexts (Dore, 2019). Being a universal phenomenon, it is not necessarily limited to a specific society or community, because small groups and communities may also have distinct ways of conceptualising humour. As remarked by Botella Tejera (2022), and as previously stated by Nash (1985), while humour is universal, the act of humour is not. Therefore, the concept of humour, which we will not try to define in this paper, includes “culture-specific references pertaining to the culture of origin which are frequently involved in humorous tropes” (Chiaro, 2010, p. 2); and this is precisely what we understand as culture-bound humour in this study.

Consequently, the focus is put on the translation of culture-specific references in audiovisual comedies, especially those that create some form of humour. As stated by Dore (2019), cultural references are not humorous per se, although they can be used to convey specific humorous features.

As for audiovisual texts, Ramière (2006) suggests that culture-specific units also encompass an additional dimension, that is, the co-existence of verbal and non-verbal signs that determine the cross-cultural transfer in the localisation process. As mentioned before, cultural references may be used parodically or ironically as a recurrent strategy (Leppihalme, 1997), as is the case with some of the passages collected for this study. In audiovisual texts, this so-called “allusive humour” (Leppihalme, p. 44) may lead to scenes deemed hilarious, which is the reason why scriptwriters seem to exploit culture-specific elements in audiovisual comedies (Dore, 2010). Moreover, some of these elements may not be considered literally funny, but ironic, incongruent, unexpected, or surprising, provoking humour in the mind of the receiver (Buijzen & Valkenburg, 2004).

Nevertheless, these references may only be understood if the target audience is sufficiently familiar with the culture in question (Leppihalme, 1997) and may be rendered incomprehensible or unfunny otherwise (Chiaro, 2008). In this regard, Botella Tejera (2017) noted that translators must be aware of the different expectations the original and the target audience may have and mediate accordingly. Thus, it is the translator’s task to determine whether the receivers of the target text might be able to recognise cultural references and perceive the implicit humour. If the target audience is not able to comprehend certain references in the same way as the original audience do, then linguists must resort to different degrees of “intercultural manipulation” (Franco Aixelá, 1996, p. 64), and the original text must thereafter be transformed to facilitate the cultural exchange (Chiaro, 2010). Therefore, a certain degree of manipulation may be found in translated audiovisual texts (dubbed versions being the ones that often display greater manipulation) although subtitlers do not underestimate the entertaining function of cultural elements (Dore, 2019). The selection of the appropriate translation strategies is especially complex when dealing with audiovisual texts, as any mismatch between the (verbally expressed) cultural reference and the image could lead to confusion (Dore, 2010). Moreover, the humorous load may be impossible to transfer, or predictably not understood by the general audience, if they are not familiar with the original cultural context. In that case, the omission of such elements may be an alternative, albeit the least desirable option (Dore, 2019).

Along with culture-specific terms, other linguistic elements are recurrent for humorous purposes and bound to cultural factors. For instance, taboo words may function as a mocking form of humour (Buijzen & Valkenburg, 2004) and youth slang serves to distort or grant different meanings to existing terms (Rodriguez, 2002), thus enabling expressiveness, irony, or the pejorative tone attached to some speakers’ lingo. In Valeria, these linguistic elements may be found, and their main function is to produce laughter or amusement among the audience, as the characters bring up cultural concepts unexpectedly or ironically in a normal conversational setting.

Perception and Translation of Cultural Humour

Recent research suggests that understanding and appreciating humour is strongly dependent on sociocognitive factors and is related to other factors such as the age and psychological aspects of the individuals and groups as well as their way of capturing humour (Juckel et al., 2016; Chiaro, 2006; Buijzen & Valkenburg, 2004). Comedies often highlight aspects of a specific nation or culture with the expectation that the audience will recognise these humorous elements and react accordingly. These aspects thereafter constitute challenges when it comes to localising and distributing said comedies in other countries and languages.

The reception of audiovisual content has been scrutinised by AVT scholars to shed light on audiovisual processing and appreciation (Gambier, 2018; Di Giovani, 2018), audience types depending on age and their preference for dubbing versus subtitling (Orrego, 2019; Perego et al., 2014), or cultural and/or humour-specific issues (Denton & Ciampi, 2012; Fuentes, 2003). For Fuentes (2003, p. 293), “the successful reception of an audiovisual production depends not only on a good phonetic and character synchrony in the case of dubbing [but] on the quality of the translation”, and viewers belonging to different language and culture groups may experience a similar humorous effect if the target text is duly marked by a significant humorous load that has been transferred using purposeful techniques.

Research on techniques for translating culture-specific elements is extensive and has led to various taxonomies. According to Franco Aixelá (1996), the choice of a particular translation technique is conditioned by several variables, such as textual factors and the characteristics of the relevant and representative elements concerned. In addition to these, one must bear in mind how the audience of the target culture may react to said localised elements. Table 1 contains a classification based on two macro-strategies that account for the degree of cross-cultural manipulation involved.

Table 1

Strategies and Techniques Applied to Cultural References in Translation (Franco Aixelà, 1996, pp. 61-64)

Some of the above conservative techniques are not (fully) applicable to translation for dubbing due to spatiotemporal restraints, such as the use of extratextual glosses, which was dismissed when designing the model of translation techniques to be used for the didactic experience described in this article. As for intratextual glosses, norm-based and synchrony-based constraints on dubbed dialogue may not always allow for the addition of words due to synchrony.

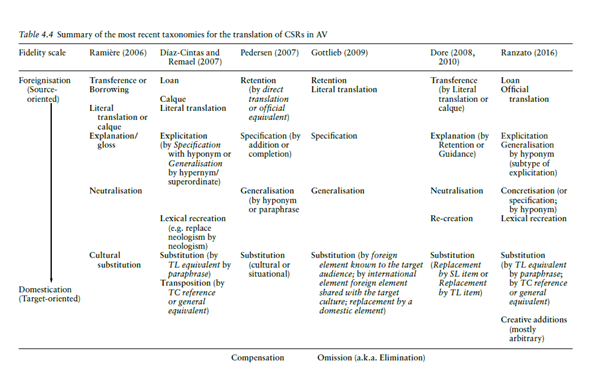

In her study, Dore (2019) provides a useful summary of the most recent taxonomies for the translation of culture-specific references (illustrated in Figure 1) that “can be subsumed under three macro-categories (retention, explicitation, and substitution) along the foreignisation-domestication continuum” (Dore, 2019, p. 187). It is worth mentioning that she particularly recommends some of these strategies - such as lexical recreation and substitution - to translate humorous cultural references, since creativity can help to retain the perlocution of the text even if not retaining the knowledge attached to the original version.

Drawing on the above taxonomies, a model of translation techniques was designed and used in the pedagogical experiment described in the Analysis section. Even though these translation strategies are applicable to the translation of audiovisual texts in general, they are somehow limited to the transfer of linguistic units. The interaction between visual and verbal elements must also be considered insofar as the transfer of cultural elements may cause a certain loss of humorous load or at least a change of relation (Martinez-Sierra, 2009).

Method

This section describes the pedagogical experiment carried out during the academic year 2021-2022 which involved a group of undergraduate students from a British institution who study Spanish as a foreign language. For this purpose, the Spanish series Valeria was used. The reasons for this selection were threefold: the fact that an English dubbed version of this series is available, the notable presence of cultural terms found in comical scenes, and the age of the potential audience targeted by this audiovisual production might be similar to that of the students. Further details on the activity, methodology, and sample are described below.

Materials

Valeria is a Spanish series produced by Netflix and catalogued in the online platform as a romantic TV comedy, based on the namesake saga written by Spanish writer Elisabet Benavent. The book series has become internationally popular, with more than three million copies sold in 15 countries in Europe and Latin America (Mantilla, 2021). The series, set in Madrid and focusing on the daily adventures of four female friends nearing thirty, deals with issues related to interpersonal relationships, sex, work, and gender. The production aims to construct a portrait of contemporary life through young adults who struggle to forge their own identity and their interactions with members of the same social group. This is undoubtedly reflected in their conversations, which are marked by Spanish Millennial slang, and replete with colloquialisms, vulgarisms, neologisms, and cultural terms.

Data Collection

For this study, an online questionnaire was set up containing a set of AVT exercises focusing on the perception of Spanish cultural references and stereotypes in the English dubbed version. The questionnaire consisted of two sections, the first one being the pre-experiment personal questions and the second one involving the actual exercises. For this study, only English-dubbed video clips were used, meaning that respondents were solely exposed to the English dialogue; however, a transcript of the original Spanish version of each relevant dialogue (i.e., translatable material for each exercise) was provided in written form, too. The excerpts contained dubbed utterances featuring at least one cultural element deemed to be funny, ironic, absurd, or mocking in Spanish. The respondents had to identify, analyse said references and then express their views and overall perception of the official translation alongside their preferred translation out of the ones proposed in the form. The practical component of the questionnaire encompassed seven exercises, each of which contained a video clip and questions. The students were prompted to carry out the following tasks:

4. Offer information and extra reading on the cultural element(s) to confirm understanding of the said cultural element.

As a rule of thumb, up to six different translations were offered in the multiple-choice task. At no point were respondents prompted to produce their own translations since this would have led to a scenario where quantification would have been too complex and the current framework might have become irrelevant. Lip synchrony and isochrony were not considered, as the main purpose of this exercise was to delve into the perception of cultural references found in an audiovisual text. In this sense, this approach may be considered as preparatory in the training for dubbing translation and adaptation. The techniques used can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2

Translation Techniques (Based on Franco Aixelá, 1996; Pedersen, 2011; and Ranzato, 2016)

The cultural elements that the students had to identify and analyse to choose their preferred translated version were selected after a close examination of Valeria’s first season. Following a detailed analysis of the original and English-dubbed versions, a sample of passages of 8 to 28 seconds containing culture-related information was produced, from which seven were deemed highly representative instances of Castilian Spanish culture-specific items. The elements were challenging, though still recognisable, by students of Spanish as a foreign language. The chosen passages are included in the Table 3.

Table 3

Original and Dubbed Dialogues Analysed and Used in the Questionnaire

The translation options given in each section of the multiple-choice task were produced by the experiment designers on the basis of the conservation and substitution strategies shown in Table 4. These options were scrutinised by external English-speaking evaluators in order to guarantee the accuracy and purposefulness of each option as well as its pedagogical value. Among the options included in Table 5, respondents were allowed to select as many as they deemed appropriate in the context given. Therefore, the culture-specific translation options provided to the participants are shown in Table 5.

Table 4

Model of the Table Used to Classify Translation Options

| Clip Number | Conservation Strategies | Substitution Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Retention (R) | Limited universalisation (LU) | |

| Absolute universalisation (AU) | ||

| Specification (S) | Naturalisation (N) | |

| Elimination (E) |

Table 5

English-Translated Dialogues After Relevant Techniques Were Applied

The pedagogical value of the questionnaire (e.g., learning about translation techniques and becoming more aware of culture-specific challenges) was deemed sufficient for distribution among undergraduate students learning Spanish as a foreign language.

Participants

This questionnaire was completed by 57 respondents, all of whom were studying Spanish as a foreign language at the undergraduate level at a British higher education institution. Most of them were in the first year of a sandwich bachelor’s degree (41 respondents or 72%), whereas 14 (25%) were in their second year, and two (3%) were in their year abroad (i.e., third year). All students were undertaking a joint programme with Spanish and another modern foreign language (20, or 35%), History (5, or 9%), Business Management (4, or 7%), European Studies (4, or 7%), Philosophy (4, or 7%), and Politics (4, 7%). Most respondents were female (47, or 82%), with only nine (16%) males, and one who identified as they/she. Given that most students were still completing their undergraduate studies, only two of them (3%) were older than 25, while the vast majority were either 19 or younger (44, or 77%) or 20 - 21 years old (10, or 17%).

Respondents came from a wide variety of cultural and national backgrounds. A total of 40 (70%) had lived most of their lives in England and four (7%) had done so in other parts of the uk, though only 30 (53%) and five (9%) were born in England and other parts of the UK, respectively. Seven (12%) were French, five (9%) were Italian, and three (5%) were Romanian. Other countries that the respondents listed included Austria, China, Czech Republic, Germany, Mexico, Poland, Russia, Spain, Switzerland, Ukraine, and the USA. In addition to the international nature of the group, the participants accessed the university programme via English; so it was soon established that the English-dubbed versions of the series would constitute the perfect opportunity for the respondents to offer a representative view in terms of how they would perceive translated culture-bound humour on screen.

Results

The findings show that, overall, learners were eager to maintain stereotypes and cultural references used for humorous purposes in audiovisual comedies, and that their understanding of these items often relies on audiovisual support.

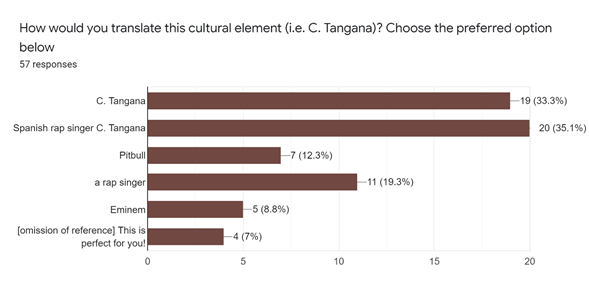

In the first clip, students were exposed to a reference to Spanish pop-rap singer C. Tangana and the fact that he might be perceived as unrefined. Visuals help to foster the humorous load in this scene due to the eccentric garments chosen by the protagonist. Most respondents (35 of them or 61%) were either unaware (19, or 33%) or unsure (16, or 28%) of the cultural element, whereas 22 (39%) answered positively. After reading the description and extra information on the singer, 40 (70%) claimed they had understood the reference. The context of the utterance and, more specifically, the visuals might have helped students to understand this was a singing celebrity as the characters wandered around a fashion store. This is directly linked to Martinez-Sierra’s (2009, p. 147, own translation) findings on visual support to better decode translatable dialogue in AVT. In his words, “although the visuals may at times hamper the translation of humour in audiovisual texts, in most cases, they have the opposite effect and help both translators and viewers [understand the relevant jokes]”.

Since most students recognised the cultural element, it is no surprise almost half of them agreed that the humour had been adequately transferred in the dubbing (25, or 44%). However, 16 respondents (28%) disagreed, and 16 (28%) were unconvinced. For the students, the most convincing approach would be conservative with specification coming first (chosen by 20 participants or 35%) and retention coming second (preferred by 19 or 33%) in their priority list, though 11 of them (19%) preferred neutralising the name of the singer (absolute universalisation). Only 7 students (12%) would choose a different Spanish-speaking singer such as Pitbull, while 5 (9%) would opt for an American rapper such as Eminem, and even fewer (4 students or 7%) would omit the reference (see Figure 2).

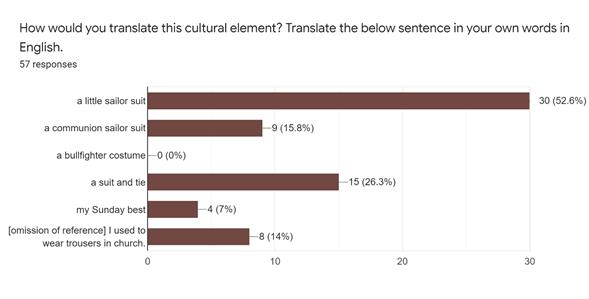

In the second clip, the cultural element marinerito referred to the traditional naval suit that Spanish boys usually wear for their First Communion. It is worth mentioning that marinerito is the diminutive form of marinero (“sailor”) and that this could have been used ironically (Figure3). The incongruity of referring to a ceremony in the Spanish Catholic community along with a traditional male costume worn by a lesbian girl is a humorous detail that would remain unnoticed by anyone unfamiliar with these cultural aspects. A very similar pattern was observed in terms of recognition: only 21 (37%) understood the cultural reference, whereas 13 (23%) did not and 23 (40%) were unsure. Opinions were more sharply divided on whether the dubbing conveyed the culture-bound humour; subsequently, 16 (28%) disagreed or completely disagreed, 24 (42%) agreed or completely agreed, and 17 (30%) were still unsure. Perhaps more striking is the fact that the vast majority of respondents (that is, 30 of them or 53%) thought a literal translation of the element (“a little sailor suit”) was the best translation in English, with only 15 respondents opting for neutralising the element (“a suit and tie”), 8 (14%) choosing the omission of the reference (“wearing trousers in church”) and only 4 (7%) preferring the more idiomatic, though gender-neutral, rendering (“my Sunday best”). The clip does not contain any visual support to suggest a more literal translation would have been preferred; however, the viewers could have inferred that the woman is a lesbian on account of both her physical aspect and the way she was flirting with one of the female protagonists (e.g., body movement, gestures and physical proximity when introducing each other).

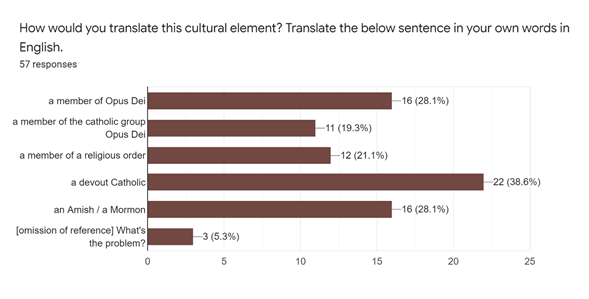

The third clip also included a religious reference to the Spanish Catholic group Opus Dei, which seemed to cause confusion among respondents insofar as the recognition of the cultural element was concerned (see Figure 4). This reference, which implies the connection between the said Catholic group and chastity before marriage, was clearly used with a humorous purpose, as the girl gestures her eagerness to have sex with her boyfriend, while he avoids her, prompting her to utter this unexpected comment. Only 12 (22%) students claimed they understood it, with most expressing a hesitant (22, 39%) or negative (22, or 39%) answer; however, once they read about the cultural element, the vast majority (36, or 63%) claimed to be able to see the point. Opus Dei is too closely attached to Spanish Catholicism and is arguably little known to English-speaking students who have had limited exposure to the Iberian religious landscape. Unsurprisingly, 23 (40%) students were not too happy about the dubbing, though 5 (9%) completely agreed and 19 (33%) agreed the humour was present in the dubbed version, while the remaining students were hesitant. Interestingly, 22 (39%) participants found the more idiomatic version (“a devout Catholic”) much more appropriate, 16 (28%) thought a natural equivalent (“a Mormon”) was the go-to option and another 16 (28%) would have chosen a literal translation (“a member of Opus Dei). The intratextual gloss and universal neutralisation scored similarly, that is, 11 (19%) and 12 (21%) respectively, whereas omission was considerably less preferred (3, or 5%).

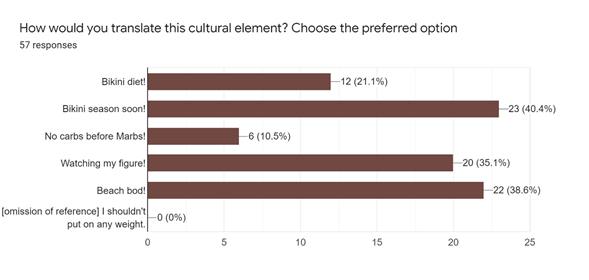

The fourth clip is an excerpt from a dinner conversation between two young couples, one of which is composed of two gay men who are discussing what to order from the restaurant’s menu. The cultural element is operación bikini (a Spanish expression promoted by the media for female target groups to indicate the weight loss process before summer), which one of them utters to remind him, in a sarcastic tone, that they are on a diet. Over half of the respondents (31, or 54%) did not recognise the reference and 12 (21%) were unsure, though only 25 (44%) still claimed they had not understood the reference once they read about it. Interestingly, many students (25, or 44%) visibly disagreed that the given translation (“my bikini”) was appropriate, or clear enough, perhaps due to a lack of visual support, and only 19 (24%) found it satisfactory (see Figure 5). The new translation options seemed perhaps more attractive: 23 students (or 40% of them) were particularly keen on specification (“bikini season soon!”) and 22 of them (39%) preferred to substitute the expression with a more natural equivalent (“beach bod!”), closely followed by 20 respondents (35%) who chose absolute universalisation (“watching my figure!). Once again, the alternative Hispanic-flavoured option (“no carbs before Marbs!”) was less preferred (6, or 11%), while the literal translation (“bikini diet”) caught significant attention (12, or 21%) and the omission option (less idiomatic and matter-of-factly longer than the rest) was not chosen by anyone. Again, the little visual context of this utterance meant that further creativity could be shown by the respondents who effectively pointed out that the official translation (“my bikini”) was perhaps clashing with the visuals (i.e., a gay man).

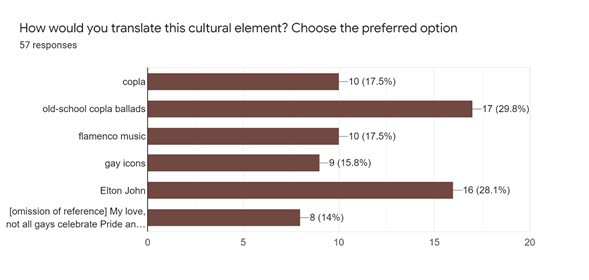

The fifth clip is the natural continuation of the above-mentioned dinner conversation, where the newly introduced cultural element was copla. The protagonist misunderstands something one of the gay men said and mistakenly assumes the latter have an open relationship. One of them argues, in a sarcastic tone, that not all gay men are in an open relationship, nor do they listen to copla music, thus playing on a gay stereotype in modern Spain. There is neither a visual nor aural component to exemplify what copla is; however, the gay couple are sitting together, and Valeria assumes this fact from the outset. Only 16 respondents (28%) were confident they had understood the reference to this type of traditional Spanish music, while 21 (37%) were unsure and 20 (35%) did not understand the concept. After reading about this stereotype, more students claimed to have understood it (27, or 47%), but 28 (49%) were still not confident (Figure 6). Opinions were divided when it comes to the transfer of the culture-bound humour in this excerpt, with only 15 students (26%) claiming that they agreed (or completely agreed) with the given translation; many, however, either disagreed (21, or 37%) or were unsure (21, or 37%). Contrary to previous clips, some respondents (16, or 28%) would have considered replacing the cultural element with one that is more widely known in English-speaking countries (“Elton John”), and a similar number (17, or 30%) would have added an explanation (“old-school copla ballads”). Again, some students (10, or 17%) would have opted for a literal translation with no explanation and others (10, or 17%) would have replaced this type of music with flamenco. Even fewer (9, or 16%) would have explicitated the meaning even further (“gay icons”) or left the reference out altogether (8, or 14%).

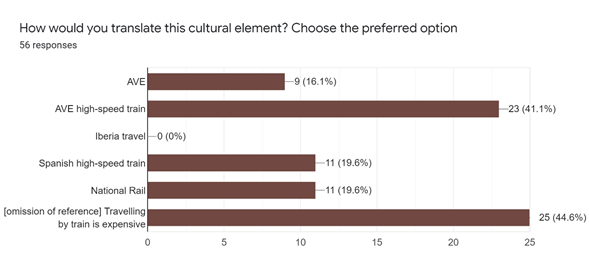

In the sixth clip, the protagonist criticises train fares, which she uses as an absurd argument to visit her family less often. Most respondents recognised the acronym “AVE” (which stands for Spanish high-speed train), with only 8 students (14%) claiming they had not understood the reference. Most (38, or 67%) agreed that the given translation (“high-speed train”) was appropriate and only 8 (9%) disagreed with said translation. It is worth mentioning that 25 (45%) would eliminate the cultural element (“travelling by train”), as was done in the English dubbing; but 23 (41%) would use the Spanish acronym and add a short intratextual gloss (“AVE high-speed train”). No respondents would choose another Spanish equivalent, but 11 (20%) would have used the absolute universalisation (“Spanish high-speed train”) or the more natural equivalent (“National Rail”). In this clip, the viewers are not exposed to any visual support, so the cultural reference appears in isolation and with little extralinguistic context that could determine its translation (Figure 7).

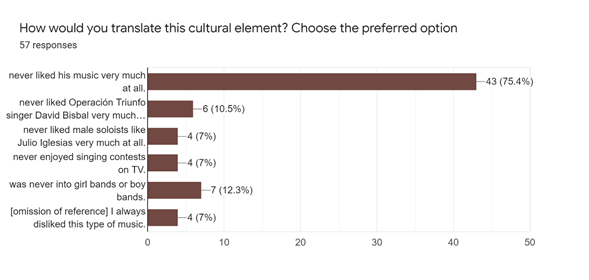

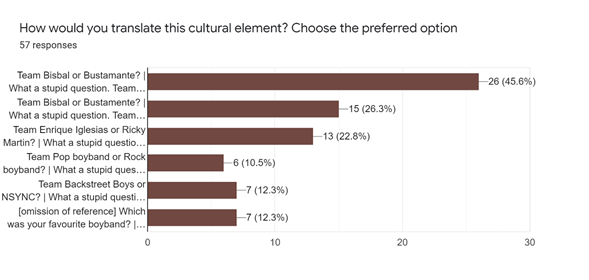

Finally, the last two clips, which have been merged and named 7a and 7b respectively, are consecutive parts of the same conversation, introducing references to three pop music singers who became famous after appearing on a talent show (Operación Triunfo) in the early noughties. Although Spanish Millennials plausibly know who the singers are, they might not be easily recognised by younger generations despite the audiovisual support offered, consisting of the lyrics of David Bisbal’s song Ave Maria and a poster portraying him holding a mic. While many students did not understand (18, or 30%) or were unsure they had understood (20, or 35%) the musical references, many did write that they thought the conversation had to do with popular Spanish singers, and so 28 (49%) confirmed their grasp of the dialogue was correct (see Figure 8 and Figure 9).

On this occasion, most respondents (43, or 75%) agreed that rendering the first cultural element literally (“his music”) was the best option. It could be inferred that respondents perhaps thought that the reference to singer David Bisbal, whose name is shown on a poster hung on the protagonist’s wall in a close-up shot, was clear enough; only 6 (11%) would have added a reference to Operación Triunfo talent show, whereas 7 (12%) would have removed the reference to the singer and used “girl bands or boy bands” instead (naturalisation). Unsurprisingly, the second cultural element was also deemed appropriate for retention (“Team Bisbal or Bustamante? What a stupid question. Team Chenoa forever”) by 26 respondents (46%), though 15 (26%) thought that it should be stressed that Chenoa is a girl (specification). Therefore, the preferred options were those in line with the visual elements, which are key to the conveyance and understanding of the cultural element, helping both the translator and the viewer. However, some students were prone to using alternative Hispanic/Spanish references - 13 (23%) would have changed them and gone for the likes of Enrique Iglesias, Ricky Martin and Shakira (limited universalisation). The rest of the techniques were less preferred, but again some students (7, or 12%) would have opted for removing references altogether and prioritising the boy vs. girl band message that this exchange connotes.

The following sections will analyse the results obtained in quantifying terms.

Discussion

All the responses to the techniques that have been discussed in this section can be seen in Table 6, which shows all options chosen by students.

Table 6

Number of Responses per Translation Technique for Each Clip

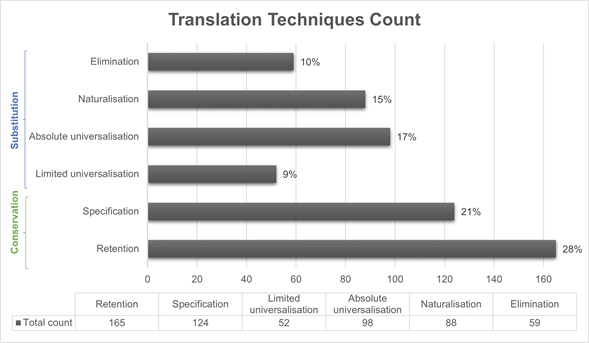

As seen in Figure 10, conservation and substitution techniques are equally distributed; overall, 49% of responses were conservation techniques, whereas 51% were substitution techniques. The literal translation options (aka retention) were the most popular choice preferred by 165 respondents (28%), closely followed by the specification (aka intratextual gloss) at 21% (124 participants). It seems that full neutralisation (aka absolute universalisation) and cultural adaptation (aka naturalisation) were the most convincing substitution techniques (98, or 17%, and 88, or 15%, respectively). Respondents were less prone to using better-known Spanish/Hispanic alternatives for the cultural elements (aka limited universalisation, preferred by 52 respondents or 9%); neither were they completely convinced about deleting the references and replacing them with a supposedly standardised version with no cultural items present (chosen by 59 of them or 19%).

Similarly to scholars who have examined the foreignisation-domestication continuum to produce taxonomies (Dore, 2019), the techniques applied in this study could be subsumed under conservation (aka foreignising or source-oriented) and substitution (aka domesticating or target-oriented). This paper has emphasised how these future translators perceive translation techniques when it comes to adapting cultural references in a more or less literal fashion. It has been observed that students seem to be keener on techniques that preserve the cultural references and perhaps explain them by paraphrasing them slightly, whereas substitution seems to be less preferable even where idiomaticity could potentially improve the naturalness of the dialogues in the English dubbings.

The above finding recalls a study by Spiteri Miggiani (2021) in which she notes a proclivity for the use of source calques and literal translation in English dubs while there is a low recurrence to the over-domestication of audiovisual productions. Having said that, it is worth mentioning that most of the respondents have received little training in professional or specialised translation, not least AVT. The respondents were enrolled on an undergraduate programme, in which the translation training provided is purely pedagogical and aims at honing their bilingual competence (i.e., comprehension and writing skills) in the target language (Spanish). This means that, despite the attempts made by translation educators, they might still attach greater importance to the comprehension and rendering of the source-text material, which in their eyes might as well mean translating as closely to the original - and its dictionary meaning - as possible according to a pedagogical translation tradition where the target audience is usually made up of fellow students or the evaluator (Steward, 2008).

Conclusions

The rapid spread of audiovisual products through SVoD platforms enables viewers to become accustomed to an unprecedented scene of globalised culture. This is particularly striking among young audiences, who tend to watch international films and have some knowledge of at least one foreign language and, therefore, its associated culture(s). An easier and better understanding of culture-bound scenes in audiovisual programmes may be achieved through didactic sequences such as the one used in this study. When audiovisual texts are contextualised in a specific cultural background, they seem to be partially untranslatable; however, the present study has proved that different strategies are eligible for rendering humour and cultural realities to meet the needs and preferences of the target audience. In this regard, this study has revealed that the sample (i.e., young adults who share a common British English language and culture and are studying Spanish as a foreign language in tertiary education) prefer an English dub that is respectful with the presence of those cultural elements (both visual and verbal) that contextualise the series.

The findings of the experiment show that the respondents of the present study were overall eager to keep cultural references as they are (i.e., conservation techniques), especially in cases where comprehension was not particularly problematic. In clips 1, 2, 7a, and 7b, the percentage of participants who fully understood the cultural reference after watching the clips ranged from 35-39%. In those cases, they particularly opposed domesticating practices such as using other Hispanic/Spanish references (i.e., limited universalisation). Specification was the most widely accepted among the Conservation techniques, along with retention for those passages constrained by the image. Substitution strategies were preferred for the passages with the lowest degree of comprehension of the cultural reference by the students (clips 3, 4, and 5, with rates of 22%, 24%, and 28%, respectively). The exception is Clip 6, the passage where the AVE is mentioned, for which 67% of respondents claimed to have fully understood the cultural reference but elimination was favoured. This datum is worth being further examined in future studies to better understand how English native speakers perceive the translation of certain references depending on the proximity to their culture as well as their degree of understanding.

When watching the dubbed version, the understanding of cultural references present in the translated dialogue somehow relies more heavily on the audiovisual support (i.e., the context in which the references appear). Even though the students were expected to have a significant grasp of popular Spanish language and culture(s), many misunderstandings were observed when analysing the open-ended questions. For instance, some respondents were misled by the reference to bikinis and the fact that a gay man uttered said sentence in Clip 4. On the other hand, many of them did not seem confident about their comprehension of said references but still reported high levels of understanding. This could also suggest the students had a good grasp of the visuals; for instance, many respondents made observations about the male clothing mentioned by a gay woman in Clip 2. Therefore, we can posit that having audiovisual support is key in the transfer, and subsequent understanding, of cultural references on screen.

This study has included a limited number of excerpts to better cater for the students’ needs. Therefore, it offers an initial attempt at examining English speakers’ cognitive and evaluative perceptions of Spanish comedies that have been dubbed into English. The findings provide relevant data that can be useful to pursue further research avenues on this front.

Future studies can further examine the perception of culture in English dubs. This audiovisual modality has recently boomed in English-speaking countries and yet requires further perception and reception research to better understand whether existing dubbings are deemed appropriate and satisfactory enough by viewers and whether foreignising or domesticating approaches are preferred when it comes to adapting cultural references on the screen.