Introduction

In this article, we discuss the use of templates, which are subtitle files “timed to film shots and audio that [are] used as a basis to originate other subtitle versions” (AVT Masterclass, 2021, p. 4). Templates “usually serve as a basis for interlingual subtitling in multilingual workflows where the content is localised into multiple languages.” (p. 4). We are concerned with a particular group of templates, which audiovisual translation (AVT) researchers term pivot templates (i.e., templates produced in a language different from the language of the original content and the final subtitles). When referring to the professional practitioner who creates (pivot) templates, we use the term templator, coined by Díaz-Cintas (2021).

The rationale for this study is that, although the use of pivot templates is a widespread practice (Valdez et al., 2023), several aspects remain unclear. First, who creates pivot templates, which audiovisual products are created using this type of templates, and which languages work as source, stepping-stone, and target languages in pivot-template workflows. Second, what challenges are involved in creating pivot templates. Third, whether there is training available for templators and what type of training is considered helpful to produce a fit-for-purpose pivot template. This lack of research-based knowledge is problematic given the increase in original content production in non-English-languages (Netflix Q4 2021 Earnings Interview, 2022) and the resulting demand for professionals with training and experience in translating into English as a pivot language (see, for instance, Bolaños-García-Escribano et al., 2021, p. 5).

To address these issues, we report on the results of a dedicated questionnaire aimed at templators and subtitler trainers; but, first, we analyse key takeaways from related research and outline the methods used in questionnaire design and data analysis.

Theoretical Framework

In this section, we outline relevant insights gained from earlier studies on pivot translation, on pivot templates, as well as on the relation between these two practices and translation directionality, English as a lingua franca, and subtitler training. In so doing, we highlight gaps in the current understanding of these pivot practices.

Pivot Translation and Pivot Templates

Pivot templates are a particular instance of pivot translation (also known as indirect translation; see Pięta, 2021). Pivot translation is a long-standing and widespread practice in many domains (e.g., Bible translation, interpreting, video game localization). However, as a subfield of research, pivot translation is recent, rarely looks beyond the 20th century, and has focused mainly on literature printed in book form (Pięta, 2021).

In the AVT industry, templates started to be commonly used with the arrival of the DVD in the 1990s (O’Hagan, 2007, p. 162) in a paradigm where non-English content was rarely distributed on a global scale and when subtitles needed to be produced fast (to avoid piracy) and cheaply (to maximise profit). To efficiently manage subtitling projects where English content was simultaneously translated into multiple languages, templates were created by native English speakers to ensure that the dialogues were reproduced accurately.

Pivot templates became a standard go-to solution in the 2010s when subscription video-on-demand (SVoD) platforms forced a new paradigm in the distribution of audiovisual content (for instance, Hayes (2021) discussed how SVoD platforms drove the increase in demand for dubbing into English). It was then that, in the global media landscape, English language productions began to give way to non-English productions, and non-English originals became more common (for instance, Netflix (2022) reported non-English original content as a higher growth area since 2015).

Stakeholders’ opinions about pivot templates vary. Language service providers tend to emphasise their positives, as pivot templates help minimise the technological requirements for subtitlers (Georgakopoulou, 2019, p. 139) and streamline outsourcing (Kapsaskis, 2011). In many pivot workflows, subtitlers only need to know how to do linguistic transposition, as timing is done by templators.

Moreover, subtitlers do not need to understand the language of the non-English content, as they will be working from the English pivot. This allows minimisation of costs (translating from and into English is typically cheaper than translating between non-English languages; see Vermeulen 2011, p. 122) while enlarging the pool of available translators (more subtitlers are working to or from English than in language combinations that do not involve English; Georgakopoulou, 2019, p. 138). Locked templates can be used as an additional risk management strategy. When using locked templates, subtitlers are not allowed to adjust timing and segmentation (e.g., no in- and out-time adjustments, no merging or splitting), proving useful when updates to the video (and, consequently, the subtitles) are expected.

In contrast, translators approach pivot workflows with mixed feelings. Some recognize the benefits: more job offers, an opportunity to broaden cultural horizons, less heavy-lifting (as timing and some detective work about culture-specific elements might have been done for the final subtitler, who can now focus on other relevant issues), and more freedom because viewers do not understand the non-English content either (Costa, 2020; Oziemblewska & Szarkowska, 2020; Valdez et al., 2023). Others see pivot templates as a threat to translation quality. A mistake in the English pivot may be replicated downstream; ambiguities and nuances in the non-English original may be filtered (Casas-Tost & Bustins, 2021; Oziemblewska & Szarkowska, 2020). If templates are locked, fine-timing and easy adaptation to local guidelines (and norms) are hindered (Georgakopoulou, 2012, p. 81). Pivot templates are also seen as a threat to translation jobs and ethics. For example, subtitlers translating from pivot can be said to take away jobs from colleagues who are already disadvantaged because of their working languages (DuPlessis, 2020).

Despite these controversies, pivot templates are unlikely to disappear. One reason for this is the streaming giants’ strategies to increase their non-English content (Rodríguez, 2017).

Pivot Template Creation and Directionality

Creating pivot templates is often combined with another commonly disapproved practice, namely L2 translation (or translation into a non-mother tongue), whereby translators work out of their L1 (or native language) and produce translations in their “first foreign” language (L2; Whyatt, 2019, p. 80). L2 translation has traditionally been considered substandard and cognitively more demanding (Pokorn, 2005). However, this view has not been consistently supported nor rebutted by research. Despite an increasing body of dedicated studies (for an overview, see Ferreira et al., 2016), we still do not know to what extent and how exactly L2 translation differs from L1 translation - both in terms of the challenges involved and the quality - although some progress has been made, particularly with regard to written translation. For example, Whyatt (2019) shows that the effect of directionality (i.e., whether translators work into or out of their L2) might be modulated by text type, translator experience, and the degree of familiarity with certain text types.

The fact that translators (need to) translate into their L2 has been acknowledged in different subfields, and many training methods have been studied (Campbell, 1998). However, in AVT, systematic research is rare. A telling example is that mainstream handbooks and encyclopaedias of audiovisual translation do not include a dedicated entry on English as L2 in AVT. Therefore, it remains unclear which challenges templators face when working from their L1 into English.

Pivot Translation and English

Pivot templates as well as pivot translation in general are intricately linked to the hegemonic status of English as a lingua franca. Research suggests that pivot translation can reinforce and undermine the hegemonic position of English (Ringmar, 2007; Tesseur & Crack, 2020). On the one hand, English pivot templates enhance worldwide access to content originally created in languages other than English, thus working as an empowering device for the cultures where these languages are spoken. On the other hand, English pivot templates can act as anglocentric filters, further exacerbating the power imbalance between English and other languages and cultures (Valdez et al., 2023). With English acting as a main default middleman, “there is a danger of cultural homogenization, whereby consumer preferences are anglicised, and English mediating is preferred to direct translation from more peripheral languages” (Pięta, 2021; cf. Ringmar, 2007).

Pivot Translation in Training

Given the conflicting opinions about pivot workflows, it is unclear to what extent creating pivot translation is part of subtitler training. To the best of our knowledge, only one study tried to partly address this issue. Torres-Simón et al. (2021) looked at the responses to their survey addressed to translator trainers, at mainstream training textbooks, at references to pivot translation in the European Masters in Translation (EMT) competences, and at the syllabi of EMT programmes. Their results suggest that there might be a disassociation between what is publicly on display and what happens in translation classrooms. EMT competences, official EMT syllabi, and published textbooks are practically silent on pivot translation; but many trainers surveyed in this study teach how to translate from a translation and, to a lesser degree, with a further translation in mind.

To recap, pivot translation in other domains has been attracting growing scholarly attention, but studies on pivot templates are recent and rare. The few studies that exist are product-oriented and focused on issues of quality (Artegiani & Kapsaskis, 2014; DuPlessis, 2020; Oziemblewska & Szarkowska, 2020; Vermeulen, 2011). Much has been said about the negative consequences of this practice; but who creates pivot templates, what challenges templators face, and what type of training is available, if any all remain unclear. These are the issues that we want to explore.

Method

We designed a comprehensive online questionnaire in SurveyMonkey to elicit templators’ and trainers’ experiences and expectations when creating pivot templates and teaching about how to create pivot templates. The questionnaire, conducted between January and March 2021, was distributed online among audiovisual translators and trainers in specialised groups on social media, through European professional translation and audiovisual translation associations, universities in Europe, and personal networks. Before its dissemination, the questionnaire was pilot tested, and the feedback was implemented. The most common error types related to survey research, such as coverage, sampling, and non-response, were also carefully considered during the questionnaire design and data collection.

To conduct this study, we abided by GDPR (European Union General Data Protection Regulation) procedures. In addition, we followed the ethical standards of research set by our universities, and we obtained informed consent from the respondents. In particular, before agreeing to participate, respondents were asked to read a written text describing the study’s general goals, how data is collected and stored, how confidentiality is managed, and the respondents’ rights. We also explicitly asked respondents to confirm that they had read and understood the information given. Participants expressly agreed for the data collected to be stored and used in research in an anonymised form. If consent was denied, respondents were sent to the final page of the survey and their information was not collected.

Data Collection and Analysis

The questionnaire consisted of two main sections with fifty-six questions in total.1 The first part was aimed at subtitlers and the second at subtitling trainers. Each main section was subdivided into two additional sub-sections. The first contained questions related to the profile of the respondents, and the second questions were about respondents’ experience in working from and/or for pivot templates. In this article, we focus on answers provided by the templators and subtitling trainers.

Different types of questions were employed: open and closed questions, including multiple-choice, verification box, and Likert-scale type questions. The Likert-scale type questions included reserve-coded statements so that respondents did not “fall into the habit of agreeing or disagreeing” (Mellinger & Hanson, 2017, p. 32), and the order of the statements was randomized to avoid primacy bias and recency bias.

In the analysis phase, the data from the closed questions were processed in Excel using descriptive statistical analysis. For the open questions, the data were exported to ATLAS.ti. Here, the data were coded and organised around recurring themes (thematic analysis) using inductive coding. In other words, the extracted codes were based on the actual language used by the respondents - their words, phrases, and terms (Saldaña, 2016, p. 105). As for the presentation of the data, when reporting the open answers, the respondents’ statement beliefs are quoted verbatim, including any typos.

Three hundred eighty subtitlers from 32 European countries answered our questionnaire. Of these, 100 indicated that they knowingly create pivot templates used for further translation into a third language. The next section reports on these 100 templators.

Results and Discussion

This section presents the questionnaire results to discuss (i) the profile of templators and template use, (ii) the challenges involved in creating pivot templates, and (iii) the availability and characteristics of training considered helpful to produce a fit-for-purpose pivot template. To do so, we have analysed 100 templators’ responses to 19 open and closed questions on their profile (demographics questions) and professional practice (see Templators). To understand if and how the creation of pivot templates is taught, the profile of these trainers, and the motivations behind not teaching how to create pivot templates, we analysed seventy-five subtitling trainers’ responses to 19 open and closed questions (see Trainers).

Templators’ Profile

Based on the 100 answers, the results show that our templators are mostly professional subtitlers (83), with seven working as volunteers and fansubbers and ten working as both professionals and volunteers. Their age ranges from 18 years to 55 or above, but most are under 44 (61).

Regarding qualifications, the data shows that most respondents (63) have qualifications in subtitling or qualifications that included modules on subtitling, with 25 holding a master’s degree, 12 a bachelor’s degree, another 12 a course or workshop certificate, five a postgraduate degree, and two a PhD. These results seem to be in keeping with the most recent reports on the training of AVT. As Bolaños-García-Escribano et al. (2021, p. 2) point out, in the last 20 years, undergraduate and postgraduate AVT modules have been created and introduced in new and existing translator training programmes in significant numbers. This has been corroborated to some extent by the survey conducted by the AVT working group of the European Master’s in Translation in 2020 (Valdez et al., forthcoming). Nevertheless, there are still reports of a perceived distance between what language service providers (LSP) need from subtitlers and the competences of (recent) graduates (Nikolić & Bywood, 2021, p. 61).

In terms of experience in subtitling, most participants (53) had more than ten years of experience: 25 participants with more than 20 years, 10 with 16-20 years, and 18 with 11-15 years. Twenty-four participants had between 6 and 10 years of experience, 19 had between 1 and 5 years, and four had less than 1 year.

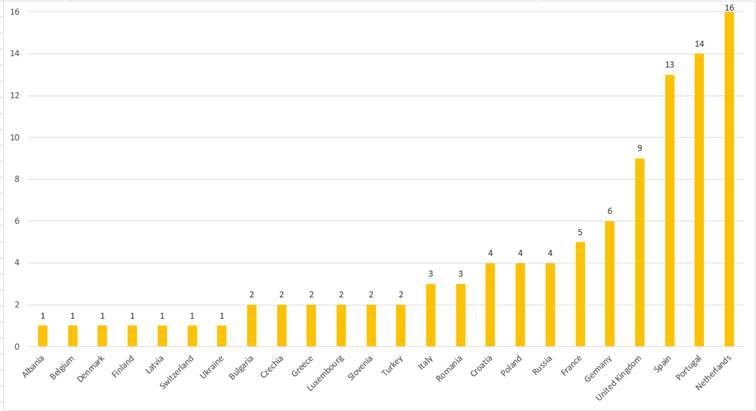

In terms of distribution per country, our templators are based in 24 European countries. Figure 1 shows the distribution by country. The six most represented countries are the Netherlands (16), Portugal (14), Spain (13), the United Kingdom (nine), Germany (six), and France (five).

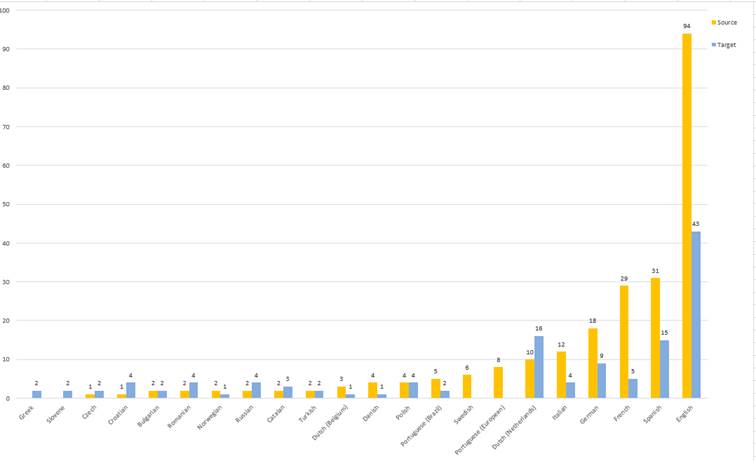

Regarding the source and target working languages that they usually work from and into, these templators usually work from and into English (94 working from, and 43 into), Spanish (31 and 15), French (29 and five), German (18 and nine), Italian (12 and four), and Dutch (Netherlands) (10 and 16). The data, therefore, suggests that English is the main source and target language independently of the templators’ native language.

Figure 2 shows the usual source and target languages with more than one respondent. The languages (source or target) with one respondent were Serbian, Bosnian, Finnish, Latvian, Yiddish, Macedonian, Korean, Basque, and Ukrainian.

Pivot Languages and Ultimate Source Languages

To identify the pivot languages and further understand the predominance of hyper-central English or central languages in template creation, we asked the respondents to indicate the template languages they usually create with a further translation in mind. As shown in Table 1, most respondents (64) reported that they typically create templates in English. This is not surprising given the traditional status of the English language as the lingua franca worldwide and in the AV sector. These numbers also suggest that our respondents create pivot templates in English, even when English is not their native language.

Table 1

Language of Pivot Templates (With More than One Respondent)

| Language of Pivot Templates | Number of Respondents |

|---|---|

| English | 64 |

| Spanish | 13 |

| French | 8 |

| German | 4 |

| Dutch | 4 |

| Italian | 2 |

| Portuguese | 2 |

| Russian | 2 |

Concerning other languages, a smaller number of templators answered that they create templates in Spanish (13), French (eight), German (four), Dutch (four), Italian (two), Portuguese (two), and Russian (two), among other languages.

We did not ask our respondents for what purpose their non-English templates are used. However, based on earlier research (Nikolić, 2015), we presume that some are used only as a technical support (i.e., subtitlers downstream only make use of the predefined timing and not the language in the template). However, in other cases, non-English pivot templates might be used as a linguistic aid too (i.e., subtitlers might use them to cut English as a go-between, for instance between closely related languages, such as Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian).

Concerning the ultimate source languages (USL), the respondents were asked to indicate the languages of the audiovisual products they typically work from when creating a pivot template. We wanted to identify the languages of the original audiovisual content when translators are asked to create templates to understand if there were signs of the increased linguistic diversity reported in the literature. Among the respondent templators, as seen in Table 2, the most common USL is Spanish (23), followed by English (18), German (14), and French (13). In other words, even though hyper-central English (Heilbron, 2010) is not the most common USL, it still occupies an important second place. It also highlights the role of English as a pivot language. It is also interesting to see Spanish, German, and French (i.e., central, globally powerful languages) occupying such prevalence in this list of USLs.

AVT Products and Their Channels

We were also interested in the type of AVT products that templators usually work with. When asked “Which AVT products do you usually create a template for?” respondents indicated that in most cases, they create templates for films (TV or cinema), series, sitcoms, and/or trailers (66; see Table 3). This is closely followed by documentaries, docudramas, and/or fly-on-the-wall docudramas (53). In a smaller proportion, our templators create templates for corporate videos, promotional videos, specialised videos and/or commercials (27), news, political speeches, press conferences, and/or interviews (15), cartoons and/or anime (14), and video clips (music, YouTubers) (four).

Table 3

AVT Products for Which Pivot Templates Are Usually Created for

The respondents were also asked about the channels or platforms where the subtitles based on their templates are distributed, and 47 indicated streaming services (see Table 4). This confirms our expectation that, for our respondents, the use of pivot language templates is most common on streaming platforms. This is followed by cable TV (30), open/public TV (27), cinema (26), and websites (20). DVD (16) and YouTube (13) gather the lowest number of responses.

Challenges and Expectations Creating Pivot Templates

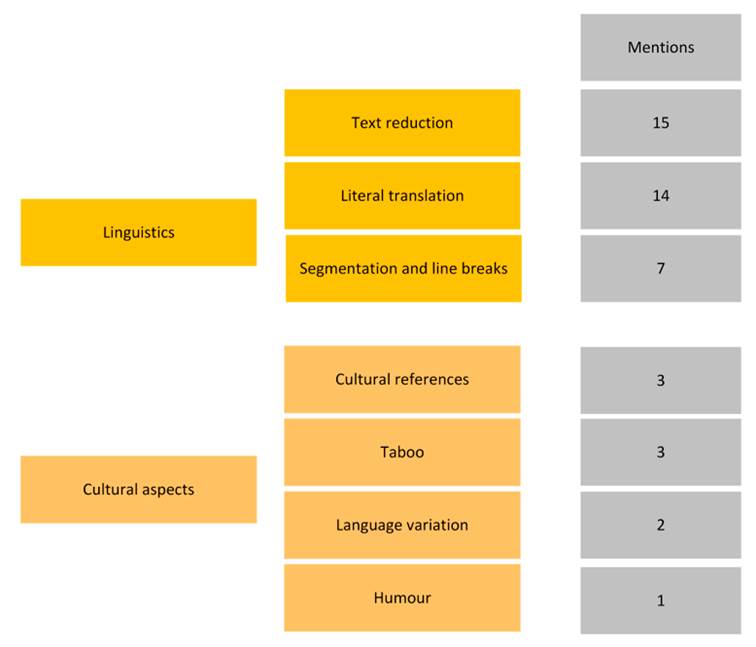

In response to the question “Tell us what is your biggest challenge, in terms of quality, when creating templates?”, answered by 81 templators, three broad themes emerged from the analysis: “Linguistics and Cultural Aspects” (45), “Professional Ecosystem” (39), and “Temporal and Spatial features” (32). Importantly, the only pivot language mentioned in the dataset was English.

Particularly revealing is how the respondents expressed their challenges. Throughout the dataset, templators conveyed concerns regarding what the subsequent translator might need from the pivot template. Commenting on this, one of the respondents wrote that their main concern was “knowing that other translators will be working from it and that I need to lay the groundwork.” Thus, when creating English-language templates, templators attempt to anticipate the needs and expectations of translators working into other languages. Templators then base their decision-making process on these expectations of others. Curiously, even though pivot templates are sometimes reported to have dual audiences (English-language viewers and subsequent translators), these templators only referred to the translators’ expectations and not the viewers (Torres-Simón et al. 2022).

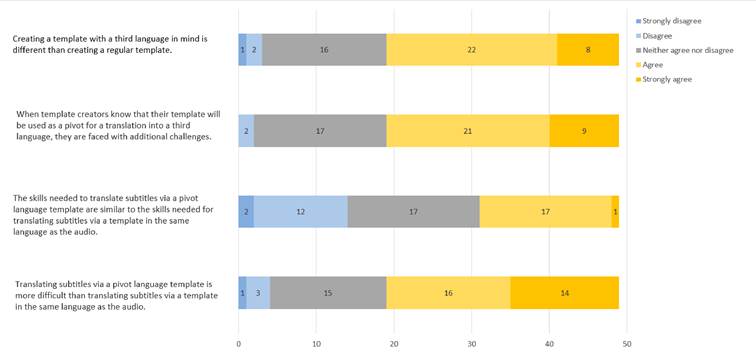

As for the most common challenges, 45 respondents expressed concerns related to “Linguistics and Cultural Aspects” (see Figure 3). Among these, 15 templators commented that one of their biggest challenges was related to text reduction or, as one respondent wrote, “condensation - because I know, the next translator will miss that information.” This is also observed when our respondents refer to a literal “translation/transcription,” indicating that they “should be as literal as possible” or that they should “adapt as little as possible so the target language can remain as faithful as possible to the original.”

Figure 3

Biggest Challenges When Creating Pivot Templates - Theme “Linguistics and Cultural Aspects” (45)

This belief that a pivot template should avoid text reduction and be as “literal” or as “faithful” as possible is very much opposed to what is recommended for subtitling without a further translation in mind. Text reduction is, in fact, one of the main recommended strategies when subtitling. For instance, as Díaz-Cintas and Remael (2021, pp. 146-147) write, “subtitles are rarely a verbatim and detailed rendering of the spoken text, and they need not be.” But this does not seem helpful when creating pivot templates, as Artegiani and Kapsaskis (2014, p. 433) have found from their analysis of French, Greek, and Spanish subtitles of episodes of The Sopranos based on pivot template files:

At the same time, because they follow the conventional and normative format of interlingual subtitles, the template files examined made use of standard strategies of text reduction, which were on many occasions blindly reproduced in the TLs. (...) [T]he consequences of text reduction choices in the template left visible traces in all three languages examined and sometimes had an adverse impact on translation quality.

Templators also expressed concerns regarding segmentation and line breaks (seven). Some templators mentioned that when segmenting, templators have to consider that “it has to work for different languages,” while others reminded that “the grammar might be very different in the third language and might need different partitions.” This suggests that, as a pivot language, English might be challenging for templators, as it might lack certain grammatical categories or syntactical structures that the USL and the ultimate target language (i.e., the language of the final subtitles) might share. Besides these considerations, others also showed that they were aware that some translators might not be allowed to change some of the spatial or temporal features of the template, like adjusting time codes or merging or splitting segments, and how negative this can be. As Nikolić (2015, pp. 199-200) points out, discussing the use of locked templates: “[W]hat subtitling companies tend to ignore is the lexical, syntactic and cultural differences between languages.”

For other respondents (nine), cultural aspects, such as cultural references, taboo, language variation, and humour are particularly challenging to anticipate. As one templator wrote, “Accuracy and making sure to anticipate any queries the translator may have in terms of slang, culture, etc. so that I can add the relevant notes to the template.” Another commented, “To consider if the English is ‘clear enough’ to be understood by my colleague, and ensure that substitling [sic] quality criteria are met, dealing with culture specific items.” These replies seem to stress that what matters in template creation is not only the quality of English. Templators’ prior knowledge of other languages and cultures matters as well, as it might help mitigate the Anglocentric filter and provide helpful information to subtitlers downstream, catering to the needs of their languages and cultures.

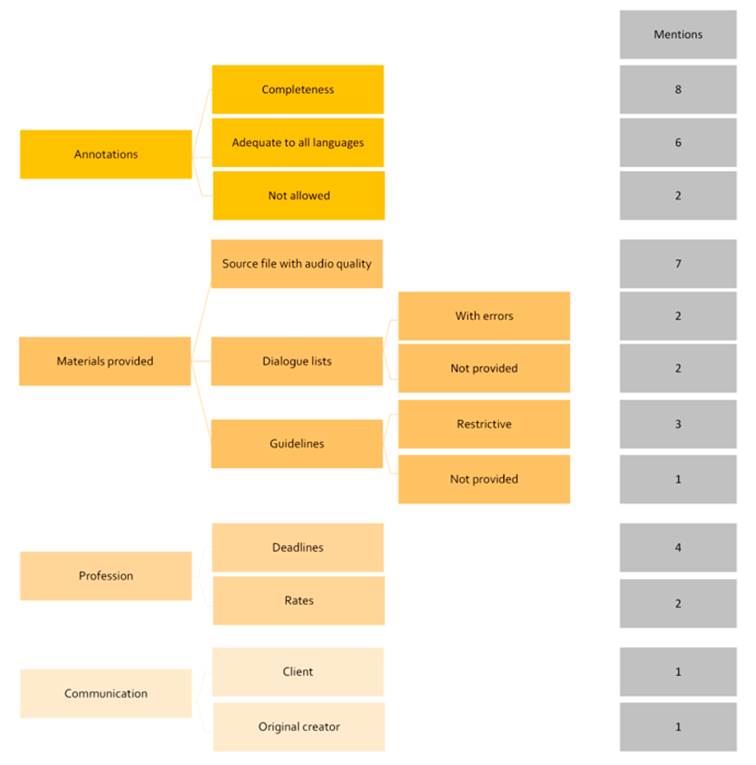

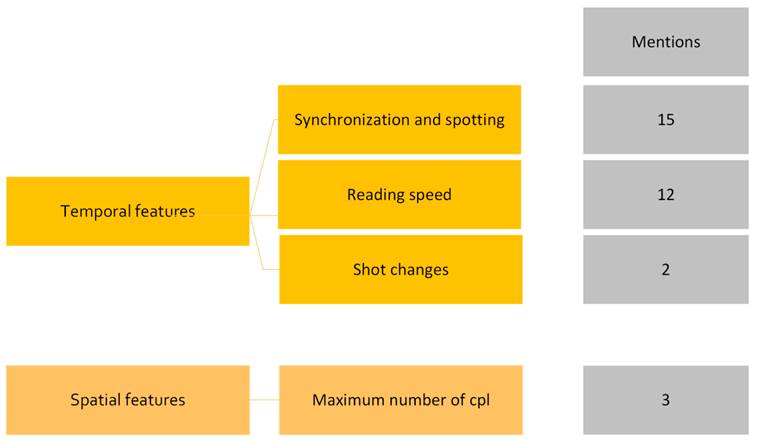

The second most recurrent challenges, mentioned 39 times, were related to the Professional Ecosystem (see Figure 4). This theme came up in discussions of challenges pertaining to annotations (16), the materials provided with the template creation task (15), the profession (six), and communication (two).

Concerning annotations, templators mainly referred to the challenge of creating complete annotations. “Knowing what to include in the annotations/comments that could help the translators when they translate from the template,” as written by one of the respondents, was recurrent among the templators that took this opportunity to discuss annotations. Others also referred to templators’ lack of “skill” when it comes to creating “significant notes” and to the need to have “vast linguistic knowledge, such as the importance of formality, gender sentence structure of languages you don’t speak” to “be helpful to other languages.”

Related to this is the challenge of creating annotations “that will fit all languages.” This related challenge was expressed by six respondents. Notably, two of our respondents referred to not being allowed to add annotations and how that hinders the process. In the words of one of these respondents, “it would be great if it were possible to leave some comments for translators to help them with translation and understanding linguistic choices in templates.” Such lack of annotation field thus seems to hold back the templator-subtitler communication in pivot workflows: what is lost in the English translation due to reduction, for example, might not be easily flagged for the benefit of subtitlers downstream because the templator lacks a dedicated space for this purpose.

In the case of the materials provided by the client or project manager with the template creation task, the principal reported challenge is related to the audio quality of the source file (seven). Other challenges include the dialogue lists that are either not provided (two) or contain errors (two). Guidelines also seem to be a source of the problem since, in some cases, they are “incredibly strict” or they are not provided at all, leaving the templator to her own devices: “I didn’t receive further instructions, so I did the same as I use to do when I translate and subtitle.”

Respondents (six) also reported challenges related to the profession itself (see Figure 5). Among these challenges, the most reported were tight deadlines. For example, one of the respondents stressed that the deadlines “do not leave much time for research.” Related to this is the challenge of rates since templators feel they are not paid proportionally to the time they need to dedicate to the template creation. Writing about this, one of the respondents commented that her challenge was “spending enough time leaving long notes when the pay is not worth the time spent.”

Figure 5

Biggest Challenges When Creating Pivot Templates - Theme “Temporal and Spatial features” (32)

Less mentioned but equally important is the lack of communication with clients or project managers and with the original creator (two mentions). “Getting information,” as one respondent points out, is particularly challenging. And to another templator, the challenge is “[n]ot having access to the creator to verify obscure dialogue.”

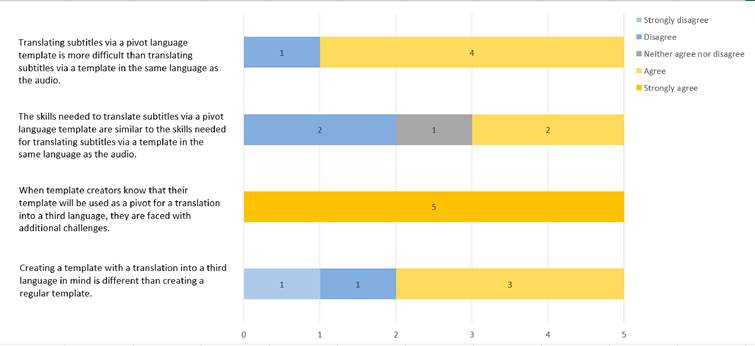

The third most recurrent challenges, mentioned 32 times, were related to Temporal and Spatial features (see Figure 5). Templators (15) reported synchronization and spotting as challenges. In this case, the challenge seems to be related to “timing properly to allow proper cps (characters per second) and CPL (characters per line) for any language the template might be used with, especially those very different from my own.” On this topic, one templator commented about the possibility of subsequent translators being negatively influenced by the template saying, “If the translator is not careful, they might rely too much on the template and not make the appropriate changes.” Templators also referred to shot changes and the maximum number of characters per line being technically challenging.

Some of the above comments seem to relate to locked templates, and to “unnecessary compressions,” (i.e., instances when timing unnecessarily reduces the space allowed, for example, by generating one subtitle instead of two; Wexler, 2021, p. 12). Many ultimate target languages might need more space to convey the meaning contained in the English translation. Given the increase of characters, the viewers of the subtitles in the ultimate target language may also need more time to read the subtitles. If the templator unnecessarily compresses the subtitle timing in the English pivot template, they might steal precious time from subsequent subtitles in other languages.

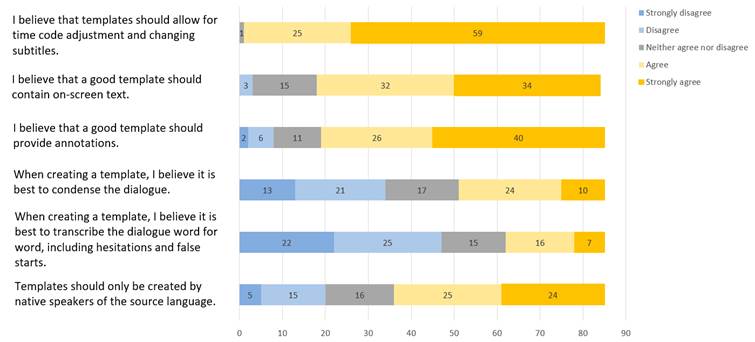

Templators were also asked to rate statements on a 5-point Likert-type agreement scale regarding their beliefs about template creation (based on Oziemblewska and Szarkowska, 2020).

The majority of the templators agreed (answering agree or strongly agree) with the first three statements (see Figure 6). These are: “I believe that templates should allow for time code adjustment and changing subtitles” (85 respondents); “I believe that a good template should contain on-screen text” (66); and “I believe that a good template should provide annotations” (66). In a lower percentage, 49 of our respondents also agreed and strongly agreed that templates should only be created by native speakers of the source language.

The statements about how to deal with dialogue elicited mixed responses. Forty-seven templators disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement, “When creating a template, I believe it is best to transcribe the dialogue word for word, including hesitations and false starts.” Interestingly, when it comes to condensing the dialogue, opinions seem to be divided: 34 respondents indicated they agree or strongly agree, and another 34 indicated they disagree or strongly disagree.

Templator training

As one of our aims was to identify if templators receive specific training (in the broadest sense) on how to create pivot templates and what type of training they have been offered, we asked not only if they “ever received help, training, guidance or instructions on how to create a template, knowing that your translation will be used by other translators,” but also what type of support they received and to what extent it was helpful.

As expected, little over half of the respondents (52) indicated that they had never received help, training, guidance, or instructions on creating a pivot template. Those who had received some form of training focussed mainly on the most helpful type of training received (see Table 5). Nine felt that specific guidelines or instructions on creating templates were helpful, while six highlighted that feedback on expectations and advice from fellow translators was the most helpful. One templator even wrote that “colleagues are the best!”

Table 5

Helpful Training on How to Create Pivot Templates

Other templators expressed that the most helpful type of training received was on English language templates focusing on annotations. For example, one templator wrote:

I think the most important thing is to always bear in mind the translator who will be using your file, in particular in terms of thinking that merging subtitles is easier than splitting them; not wasting time creating unnecessary annotations (such as providing a link to a website for proper nouns that translators can easily research themselves or will already know); taking care when choosing how to segment your subtitles, e.g. thinking about what translators will be able to edit out and what they will need to include and segmenting your subtitles accordingly.

For two participants, the type of academic training that they received, for instance, in their ma in Translation, was particularly helpful, while one templator made a point of writing that “academia unfortunately is not able to provide sufficient training for the realities of the market per se.” Q&As with project managers, inhouse training, video training, and expert training were also mentioned as helpful.

Even though most templators focussed on their most positive experiences, a small number took the time to indicate what was least helpful. For them, general training on subtitling and spotting was described as usually short and superficial. For instance, one templator wrote, “Mostly I have received general training on time cueing (not useful, as I already knew how to).” Online instructions or “on-line guides” were also considered the least helpful, alongside general subtitling guidelines.

Trainers

Seventy-five subtitling trainers from 24 European countries answered our questionnaire. Of these 75 trainers, 17 trainers reported teaching how to translate from pivot templates, and five trainers indicated that they teach how to create a pivot template with a translation into a third language in mind. This was somewhat expected given Torres-Simón et al.’s (2021) findings.

This section draws on the answers of the 70 respondents who indicated that they had had experience in teaching subtitling but did not train subtitlers on how to create pivot templates. It also compares these 70 repondents to the five respondents who have trained pivot templators.

Trainers’ Beliefs

We asked our trainers to rate a series of belief statements about pivot templates and training (from strongly disagree to strongly agree). We first discuss the data for the 70 trainers who do not teach template creation.

As shown in Figure 7, most respondents (30) believe that creating a template with a third language in mind is different from creating a regular template; therefore subtitlers face additional changes when creating pivot templates. What is more, Figure 7 shows that, according to most respondents (30), translating subtitles via a pivot template is more complex than translating subtitles via a template in the same language as the audio (answering agree or strongly agree to the three statements).

Opinions seem to be divided regarding the skills needed to create pivot templates. While 14 either disagree or strongly disagree that “the skills needed to translate subtitles via a pivot language template are similar to the skills needed for translating subtitles via a template in the same language as the audio”; 18 either agree or strongly agree with this statement. It is also important to acknowledge that the number of respondents that indicated that they “Neither agree nor disagree” seems to be high (above 15) and might suggest that they did not have a clear opinion on the matter or that the statements were not sufficiently clear.

Figure 8 presents the view of pivot template trainers regarding competences and task difficulty. The pivot language covered in their training was, in all cases except one, English. The exception was a pre-conference workshop on English-French-Japanese translation. The main difference is that, in this case, most trainers agreed that pivot template creation is more challenging when compared with templates in the same language as the audio. For most of our trainers (four), it is also clear that translating via a pivot template is more difficult than translating via a non-pivot template.

All in all, their answers do not diverge significantly from answers given by trainers in the first group.

Motivations Behind not Teaching Subtitlers How to Create Pivot Templates

We also asked the subtitling trainers that do not teach how to create pivot templates to describe, in an open question, their motivations behind it, and their answers were quite telling. The main reported motivations for not teaching template creation were (1) time limitations (mentioned 14 times), (2) not a common practice (10 times), (3) pivot translation should not happen (eight times), (4) not part of the curriculum (seven times), and (5) does not involve a specific set of unique skills (three times).

With 14 mentions, time constraints were the main reason pointed out by the subtitling trainers that do not teach students how to create pivot templates. In the words of one respondent, trainers “lack […] teaching hours to reach the subject.” Data analysis also revealed that this “insufficient time to cover those aspects” was mainly associated with another factor: one trainer felt “there are more relevant issues to cover first,” and other respondents who mentioned time constraints echoed this feeling.

From their answers, it seems that our trainers mostly teach the “basics” or a basic set of subtitling skills. Addressing this issue, another trainer wrote, “In order to master template translation and create any kind of templates, I find it important to first master subtitling from scratch. I would need a larger module to teach creating templates, which I do not, unfortunately, have.” These comments might suggest that training sometimes aims to equip students with skills that are needed for established practices (localizing out of English), and not so much for emerging practices that are already on the horizon (localizing into English).

The second most mentioned motivation, referred to 10 times, was that pivot translation is not a well-established translation practice. “Doesn’t seem like a particularly useful skill in our national market”, “it’s been a rare task”, or “not all players use templates” are comments that illustrate this point of view. On language combinations, one of the respondents wrote for instance, “As things stand, there is no call for this in my language combination (DE>EN). There is not enough German content that is localised into enough other languages, so pivot templates are very rarely used”. This last view, in particular, seems to be countered by the data discussed in “Templators’ profile”: German is the third most common USL for our respondents.

The third most mentioned motivation to avoid teaching the creation of pivot templates, referred to eight times, was that pivot translation should not be practised. From the analysis, this motivation seems to be stemmed mainly from the belief that translators should translate into their native languages only and from a language and culture they are proficient in. Three of them, for example, commented the following:

Example 1: The normalization of templates in certain countries means stealing work from translators who actually have the skills to translate from source languages other than English and who can do a better job (i.e., avoid translation mistakes, understand the cultural references and choose for themselves whether or not to keep them, explain them, etc., for instance). Subtitling from templates should be a last resort, not the default.

Example 3: The importance of knowing the original language is pivotal to creating a quality end product.

The two least mentioned motivations were that pivot template creation is not part of the curriculum (seven times) and does not involve a specific set of unique skills (three times). As for the latter, some trainers expressed that they “don’t think it’s different from creating a general template” or that subtitlers can “build upon knowledge of template creation in general,” indicating a lack of awareness of the specific challenges of pivot template creation.

Overall, the motivations for not teaching translators how to create pivot templates seem to clash with pivot templators perspectives not only on the challenges they face when creating pivot templates (see Challenges and expectations when creating pivot templates) but also on their opinion on what they consider to be helpful training (see Templators’ training). As one templator commented, “The more training there is, the better, I never had a training which was not helpful.”

Unfortunately, little was reported by the group that teaches template creation in a similar open question on reasons to teach, so a solid comparison cannot be established. Therefore, we can only speculate that differences will lie in the intrinsic and extrinsic motivations discussed above.

Conclusions

Our study partly overcomes limitations of earlier studies, but it has its own limitations. Despite the rigorous design, four participants reported difficulties understanding some questions, so their answers were not included in the analysis. Moreover, our data focuses on respondents based in Europe, with a possible over-representation of respondents from the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain. English pivot templates are a global phenomenon; therefore, our findings only portray a part of the complex picture of ongoing changes in the subtitling English-language industry. Still, the study offers valuable insights into AVT practices for English as a pivot language and opportunities to reflect on ways to move forward.

We characterize, for the first time, templators (their profile and professional practices) and their training. We highlight the challenges and expectations when creating pivot templates and trainers’ motivations behind not teaching about how to create pivot templates. Our data suggest that creating pivot templates is a common practice. Of the 380 subtitlers from 32 European countries, 100 create pivot templates, 83 of which also translate from pivot templates. It is clear from the data that translating from templates is an almost ubiquitous activity for subtitlers, especially for subtitlers working for SVoDs. Most of these templators are seasoned professionals (53 participants had more than ten years of experience) with formal qualifications in subtitling, and the majority of the respondents (63) have qualifications in subtitling or qualifications that included modules on subtitling. For our respondents, English is the main source and target language, independent of the templators’ native language. Most respondents (64) reported that they typically create templates in English. Among the respondent templators, the most common USL is Spanish (23), followed by English (18), German (14), and French (13). This goes to show that although English is not the most common USL for pivot templators, it still occupies an important second place.

Templators from our dataset face various challenges related to linguistic and cultural aspects, their professional ecosystem, and the temporal and spatial features of templates. However, our findings suggest that teaching the creation of pivot templates is rare, particularly when compared to training in subtitling in general or training on how to translate from pivot templates. Of the 75 subtitling trainers from 24 European countries, only five teach how to create pivot templates. The pivot-template-making training offered comes mainly from the industry and not academia. This is problematic because (a) in-house training does not typically cover issues related to templator ethics or the sustainability of the translator profession and (b) translator training and professional codes of conduct are underpinned by a rationale that prioritises translating into the subtitler’s native language (Delabastita, 2008) and, based on our responses, the key worries of templators are not addressed in training.

Against this background, and based on the respondents’ insights, we make suggestions that academic trainers, industry, and researchers might want to take on board. First, to address the problematic issue of text reduction in pivot templates, English templates that serve dual purposes should be avoided. Instead, two sets of English subtitles should be created. First, the English subtitles should be created for viewers and the pivot texts to be translated further. Second, subtitlers working from pivot templates should be allowed to adapt the spatial and temporal features since these considerations can be culture and language-dependent. Importantly, pivot templators should be informed if the templates will be locked or not since this affects the way they time and segment the content.

Third, to help pivot templators anticipate the needs of translators downstream, trainers in academia should teach how to create helpful annotations, so as to make explicit what has become implicit in the pivot translation. Pivot language translators reported difficulties in selecting what to foreground. Thus, source culture subtitlers might be more aware of the elements to highlight, but would need to be trained in L2 translation. Multilingual classrooms and cross-cultural remote collaborations might be a fertile ground for such training.

Fourth, to address the issue of English lacking many of the grammatical categories that USL and UTL might have, the use of non-English pivot templates should be studied more systematically, as these templates might be a valuable alternative for some language combinations.

Fifth, software developers should optimise the annotation fields on their subtitling platforms. Templator annotations should be easily accessed by all translators downstream, facilitating templator-subtitler communication. They should not be approached as add-ons stashed away for sporadic use (e.g., for notes to self or for quality control only).

All things considered, if the aim is to better prepare AVT students for current and future challenges, much can be gained from teaching non-English-language native speakers how to create English-language templates.