Introduction

As advertising is becoming global, the role of translation in the creation of campaigns has gained importance and given rise to the new professional profile of transcreation, i.e. a term that combines words’ translation and creation. Semiotic and cultural adaptation, as well as creativity, are components of translation, especially in the audiovisual field. These components are brought to the fore in transcreation, which has become a specific profile of translation in advertising and marketing, where freedom and adaptation to target culture and customers are crucial.

This article focuses on arguably under-researched issues such as transcreation in advertising translation. This is less researched than film translation despite the “transcreational turn” in translation studies (Katan, 2016). We look at aural aspects in audiovisual translation (AVT), with a focus on multilingualism and song, rhythm, and rhyme, which are also less researched than visual elements in AVT and advertising translation. Additionally, an under-examined issue addressed here is the translation into English -especially relevant in international advertising. All these aspects are studied in connection with the translation of Mediterráneamente, an acclaimed beer advertising campaign.

Being traditionally a local product, Spanish beer has undergone significant changes in recent years. It has been marketed internationally and English has become the target language for its global advertising campaigns. The brand Estrella Damm, produced in Barcelona, has adapted to this situation and improved its international positioning whilst enhancing its geographical origins and culture. In 2009, Estrella Damm started its first Mediterráneamente campaign focusing on the association of beer with the Mediterranean regions, its culture, enjoyment, and sustainability.

This article examines the strategies of English translation in Estrella Damm campaigns between 2009-2021. Although this brand creates its campaigns in Catalan and Spanish, they are also available in English, mostly via subtitling, on the company’s British website and YouTube channel. (In this article, the names of the slogans are quoted in English, given the language combination analysed in this article: Spanish-English. On the British Estrella Damm website and YouTube channel, the slogan Mediterráneamente is kept in Spanish).

We analyse strategies for translating the following prominent elements in the campaigns: slogans, cultural references, multilingualism, and songs. The article provides an overview of translation strategies throughout the campaign and a detailed analysis of specific commercials in which the transcreation of elements is involved. After an introduction to Estrella Damm’s communication campaign, the theoretical framework revolves around transcreation in advertising translation. The method section describes the corpus and the rationale for translating the following aspects, which will be dealt with in specific sections: cultural references, multilingualism, and transcreation of the aural, which are then summarised in the general conclusions.

Estrella Damm’s Communication Strategy for National and International Markets

Spain is one of the largest beer producers in Europe but one of the countries with the lowest beer consumption (Statista, 2022b). From 2008 to 2020, the average beer consumption per capita was under 55 litres per person a year (Statista, 2022a) while countries such as Germany or Austria consumed twice as much (Statista, 2022b). In 2020, the Czech Republic consumed 135 litres per person a year, Austria, 100, and Germany, 95. Mediterranean countries are at the bottom of the list. In 2020, Spain’s consumption was 50 litres per person a year, Cyprus, 43, Malta, 39, France, 33, Italy, 31, and Greece, 28 (Statista, 2022b). Nevertheless, beer is still one of the most frequently consumed drinks in Spain (Statista, 2022c).

According to Brand Finance (2021) and its World Brand Finance Beer Ranking, the most valuable beer brands in Spain in 2021 were Estrella Damm (position 24), Mahou (position 35), and San Miguel (position 49). Estrella Damm, which now leads the ranking in Spain, was not in such a good position before 2009 when this traditional brand was losing its luster. This was partly due to advertising campaigns that did not have a unique selling proposition. The company had previously presented a huge variety of campaigns but could not transfer a clear and continuous perspective into their communication actions. In fact, Estrella Damm’s position did not start to improve until it changed its communication strategy in 2009.

That year, their first Mediterranean campaign was launched with a strong strategic communication approach. This enabled the brand to reconnect with young people through social networks. The campaign utilised a remarkably effective transmedia mix (Álvarez-Ruiz & Castro Patiño, 2021, p. 20). As stated by Estrella Damm’s creative director, Oriol Villar, the Mediterranean campaigns are aimed at disseminating the Mediterranean lifestyle precisely because the brand is strong in this geographical area and advertising reinforces its identity. For him, advertising puts a magnifying glass on one part of the brand and amplifies it (Interview, Villar, October 4, 2021).

Even though the brand’s main target audience is the local market, internationalisation is a pillar of Damm’s strategic plan. Since Spain is the second most popular tourist destination for British people, Estrella Damm considers that it is useful to run advertising campaigns in the United Kingdom. There, they use the same campaigns on the Mediterranean lifestyle to be coherent with their communication strategy.

Damm’s Mediterranean campaigns work for local people as they transmit a feeling of pride and belonging. For foreigners, the ads work as they make them feel good by bringing back beautiful memories of their holidays in Spain. However, the role of the campaigns is very different in each country. In Barcelona, Estrella Damm can be found almost everywhere and it is a common beer. In contrast, in the UK or the United States, this brand can only be found in some places, and it is a special beer (Interview, Villar, October 4, 2021).

Theoretical Framework

The term transcreation has progressively been used in translation studies, particularly, in the context of advertising translation. In this section, we present (i) how the term has been used in this context and has evolved as a translation strategy, (ii) some key factors involved in it, and iii) a few challenges of translating aural elements, i.e. songs and rhyming texts.

Transcreation in Advertising Translation

Research on advertising translation has flourished, especially, after the turn of the millennium, and has emphasised the need for cultural, semiotic, and target-user transfer (Adab & Valdés, 2004; Torresi, 2021). The terms translation, adaptation, and transcreation coexist in the literature on advertising translation in several ways, sometimes interchangeably. We understand the first one broadly as any act of linguistic and cultural transfer. In this sense, we consider that both adaptation and transcreation are translation strategies used to carry out linguistic and iconographic transfers to the conventions and social practises of the receiving culture. In the nineties, adaptation was a common term. For example, Smith and Klein-Braley (1997) define adaptation as “the technique which makes the necessary tactical adjustments in terms of addressee needs and expectations, cultural norms, frames of reference” (p. 183). Increasingly, and particularly in the new millennium, transcreation has been employed in the context of advertising translation (Gaballo, 2012). According to Torresi (2021), transcreation is “a type of adaptation that involves copywriting and, possibly, prompting the creation of new visuals for the promotional material, rather than relying on the same verbal and visual structures of the source text” (p. 199). Thus, there is continuity with the sense of adaptation as a translation strategy.

However, Torresi’s definition adds the following specification: “in this approach, the translator is seen as a creative professional with highly developed language skills and an in-depth understanding of social, cultural, legal and promotional conventions currently in place in the target culture” (Torresi, 2021, p. 199). This has specific consequences for translators such as higher specialisation and remuneration and the explicit brief of freedom in translation: “the process of trans-creating an entirely new text to accommodate the expectations of the target group requires more flexible deadlines and higher price” (Torresi, 2021, pp. 12-13).

The current advertising scenario, which combines globalisation and localisation, has fostered this new professional profile of translation. Transcreators have the explicit brief to incorporate semiotic adaptation, drawing from their expertise in content localisation, and “the creative dimension of the translation process, which is particularly necessary in marketing” (Fuentes-Luque & Valdés, 2020, pp. 81-82). When we state that transcreation is a new profile, we mean a new professional profile, especially in the advertising field. This is compatible with the view that creativity, as well as semiotic and cultural adaptation, are integral parts of translation.

The boundaries between the concepts of translation and transcreation have been the focus of a rich discussion in translation studies by specialists in audiovisual translation (Pedersen, 2014; Spinzi & Katan, 2014; Chaume, 2018), advertising translation (Torresi, 2021), and illustrated literature (Oittinen, 2020). It is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss all the theoretical issues involved in the alleged “transcreational turn” of translation studies (Katan, 2016), which include a need to find a new concept of equivalence that embraces new types of relations between original and target texts (Chaume, 2018, p. 84). Scholars generally agree that the ingredients of transcreation are present in translation. For example, Torresi (2021) uses translation in the context of advertising and gives the term its etymological meaning of transfer: “the transfer of a text, concept or promotional purpose across languages, cultures, and markets. This by no means implies that translation is limited to the verbal dimension, nor to texts as seen out of their real-life contexts” (Torresi, 2021, p. 5). Nevertheless, there is also agreement among specialists and scholars that the label transcreation is increasingly used by the translation industry (e.g. Balemans, 2016) and analysed by scholars (Carreira, 2020; Gaballo, 2012) to emphasise its value as an addition to translation (Pedersen, 2014). Even then, following Torresi (2021), translation is a general term and transcreation, a translation strategy (p. 5).

Key Factors Involved in Transcreation

As a translation strategy, transcreation involves four factors: creativity, cocreation, internationalisation, and adaptation. We discuss them in this subsection.

From an advertising perspective, Villar considers that creativity implies problem-solving in different ways (Interview, Villar, October 4, 2021). More specifically, language creativity can involve the “purposeful use of non-standard language [where a specific trope can be replaced] with another creative device that engages the reader [or viewer] with equal intensity” (Torresi, 2021, p. 142). This engagement is all-important and can relate to the emotional dimension of translation: “Transcreation is not only about communicating effectively but also affectively, establishing an emotional connection between the audience/the customer and the message” (Dybiec-Gajer & Oittinen, 2020, p. 3).

Another key factor is cocreation or, at least, the dialogue or negotiation between translators and creative directors. Cocreation can entail suggesting alternative versions to provide creative language (Torresi, 2021, p. 142) or different versions for close-ups to help lip-syncing, for example, of Spanish word vale or Catalan word d’acord, uttered by Dakota Johnson in Estrella’s Vale 2015 commercial (El Periódico, 2015).

The following factors, internationalisation and adaptation, often coexist in transcreation briefs and reveal current tensions between globalisation and localisation. As regards internationalisation, in global advertising campaigns, translation is envisaged from the outset and text is often translated from one into many languages or markets (Pedersen, 2014, p. 65) and transferred from one culture to a different one.

Hence, cultural transfer has been emphasised in research on advertising translation (e.g. Adab & Valdés, 2004). Adaptation is a specific factor of transcreation that “accommodates the conventions of the target language and culture, the canons of literary genres thereof, and the expectations of the target readership/audience” (Torresi, 2021, p. 195). This can involve specific adjustments or completely “re-building the entire promotional text so that it sounds and reads both natural and creative in the target language and culture” (Torresi, 2021, pp. 4-5). This frequently implies adaptation to local legislation that can prompt the creation of new “visuals”, that is, “each visual element of a (promotional) text. Also, the typeset version of a print advertising or promotional text, complete with pictures and any other visual material that accompanies the written text” (Torresi, 2021, p. 200).

According to Chaume (2018), “types of shots can also be manipulated in order to share a domesticated product that, allegedly, satisfies a specific target audience” (p. 96). For example, advertising in the UK does not allow images of people drinking beer while in the water. Therefore, when Estrella Damm commercials are filmed, specific shoots are taken for the English versions (Interview, Villar, October 4, 2021). The specific role of translators in adapting the commercials to target cultural or legal aspects depends on the degree of cocreation and their presence in the workflow, which varies greatly (Carreira, 2020).

In short, “transcreations are all forms of semiotic adaptation and manipulation where some or most - if not all - semiotic layers of the original (audio)visual product are localised” (Chaume, 2018, p. 96). In academic literature, greater emphasis has been put on the visual elements of the text and, arguably, not so much on its aural elements. An exception to this are studies on dubbing or illustrated children’s literature and the importance of rhythm in stories for reading aloud (Oittinen, 2020).

Challenges of Transcreating Aural Elements

Transcreating aural elements such as songs or rhyming texts is common in advertising. Since the corpus of this study comprises sung translation and subtitled songs, both are tackled succinctly.

Low (2016) summarises the challenges of musical translation through the sporting metaphor of the pentathlon and its five components: singability, sense, naturalness, rhythm, and rhyme. Low analyses each of these separately but stresses the flexibility that is required and the relative importance of each individual aspect for an overall effect. Professional practise is pragmatic and defends “tweaks” or small adjustments, especially regarding rhythm (Low, 2016, pp. 100-102), which can also be extrapolated to other pentathlon principles like rhyme. In advertising, flexible, imperfect rhyme schemes might be used in rap music or the translation of musicals (Espasa, in press). If rhyme has to be translated, this needs to be anticipated: “Any strategic decision to use rhyme needs to be made early in the process, so that some rhyming words (the crucial ones) can be found early on” (p. 103).

Subtitling of songs has been tackled by Franzon (2008) and Díaz-Cintas and Remael (2020, pp. 195-200), among others. Subtitled songs “belong to the category of song translations meant to be read rather than sung” (Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2020, p. 196). Yet, the simultaneous reception of subtitles and music is a relevant factor since “viewers read the subtitles while listening to the music and lyrics at the same time, which may have an impact on the translation, rhythmically speaking” (Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2020, p. 196). Therefore, all the pentathlon factors mentioned above (singability, sense, naturalness, rhythm, and rhyme) are relevant, even if sense tends to be the subtitler’s main concern.

Díaz-Cintas and Remael (2020) provide criteria for choosing the songs to translate. Usually, thematic or plot relevance is an important criterion. However, songs “suggesting a mood or creating an atmosphere […] must be given special attention” (Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2020, p. 196) even though they are often left untranslated. As regards formal aspects, they discuss the challenges of deciding whether it is important to preserve the rhythm and the rhyme of song lyrics since subtitles are a supporting translation and would not detract too much attention from the images and soundtrack. Nonetheless, they also report Franzon’s (2008) claim that respecting the prosody of lyrics in subtitling can actually enhance their readability. Low (2016) states that the specific relevance of rhyme in songs should be considered. For Corrius and Espasa (2022), “the decision as to when and how to subtitle songs shows the delicate balance between logocentric and musicocentric approaches” (p. 40) that is, between attention to the verbal or the musical aspects involved.

Method

We used a descriptive case study methodology to analyse and compare 14 Estrella Damm commercials between 2019-2021, which are available on the company’s website and YouTube channel and included in Table 1.

Data Collection

For our analysis, we worked with the Spanish version and the subtitled English version of 14 commercials (detailed in Table 1) that are part of the Estrella Damm Mediterráneamente campaign. These ads were aired on Spanish television between 2009-2021 and can be found on the internet, where they have been viewed many times. Although we examined the Spanish version as the source text (ST), according to Villar, the ads were recorded in either Spanish or Catalan depending on the director’s language (Interview, Villar, October 4, 2021).

Table 1

Mediterráneamente Commercials: Corpus of Analysis

| Year | Name of the Ad | Director | Celebrity | Song/Band | Visualis. (Millions) | Likes (Thousands) | Links |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | “Formentera” | - | - | Summercat/Bille the Vision & The Dancers | 7 | 16,8 | https://cutt.ly/9Hwr0dI |

| 2010 | “San Juan” | - | - | Applejack/The Triangles | 8,1 | 16,6 | https://cutt.ly/SHwte90 |

| 2011 | “elBulli” | Isabel Coixet | Ferrán Adriá | I wish that I could see you soon/Hermann Düne | 2,5 | 4,8 | https://cutt.ly/9Hwtpd1 |

| 2012 | “Tramuntana” | - | - | You can’t say no forever/Lacrosse | 5,1 | 12,9 | https://cutt.ly/zHwtRpE |

| 2013 | “Love of Lesbian” | - | - | Fantastic Shine/Love of Lesbian | 3,5 | 10 | https://cutt.ly/7HwtSSx |

| 2014 | “Entrena el alma” | Claudia Llosa | - | La música es cultura/The Vaccines | 1,5* | 3,1* | https://cutt.ly/vHwdVkR |

| 2015 | “Vale” | Alejando Amenábar | Dakota Johnson | Our place/Maïa Vidal | 8,9 | 39,6 | https://cutt.ly/7Hwt3rR |

| 2016 | “Las pequeñas cosas”/“The little things” | Alberto Rodríguez | Jean Reno | Those little things/Ramon Mirabet | 7,4 | 26,5 | https://cutt.ly/5HwyeAk |

| 2017 | “La vida nuestra”/ “La vida nuestra (Our Life)” | Raúl Arévalo | Peter Dinklage | (Don’t fight it) Feel it/Aron Chupa | 8,6 | 20,4 | https://cutt.ly/qHwyaao |

| 2018 | “Álex y Julia” | Dani de la Torre | Michelle Jenner | The place to stay/Oriol Pla y Michelle Jenner | 10,7 | 13,8 | https://cutt.ly/ZHwyhM1 |

| 2019 | “Acto I. Alma”/“Act I. Soul” | Nacho Gayán | Claire Friesen | Otra forma de vivir / Joan Dausà ft. Maria Rodés, Santi Bames | 11,7 | 42,3 | https://cutt.ly/mHwiymf |

| 2019 | “Acto II. Amantes”/ “Act II. Lovers” | Nacho Gayán | - | Otra forma de vivir/Joan Dausà ft Maria Rodés, Santi Bames | 10,5 | 19,9 | https://cutt.ly/jHwiiLQ |

| 2020 | “Acto III. Compromiso”/“Act III. Commitment” | Nacho Gayán | - | Otra forma de vivir/Joan Dausà ft. Magalí Sare | 14,5 | 14,5 | https://cutt.ly/gHwipXO |

| 2021 | “Amor a primera vista”/“Let’s try together” | Nacho Gayán | Mario Casas | A ver qué pasa/Rigoberta Bandini | 14,8 | 6,7 | https://www.estrelladamm.com/en/lets-try-together |

[i]Source: based on Álvarez-Ruiz and Castro Patiño (2021).

Data Analysis

Following the case study methodology, we used several qualitative techniques, which are commonly employed in translation, to analyse the most relevant content of each ad. We gathered information from the scientific literature and data from official sources. We carried out two semi-structured interviews, the first with Oriol Villar, a creative director with Estrella Damm (October 4, 2021), and the second (February 8, 2022) with Tony Gray, who has been responsible for the translation of Estrella Damm’s Mediterráneamente campaigns (from Spanish into English) since 2015.

For the content analysis we designed an Excel sheet in which we registered information about the commercial, location, slogan, cultural references, music and soundtrack, and languages used in the ad. Then we selected the commercials that contain more text (2015-2021), either spoken or sung in Spanish, where the role of translation is more relevant. Finally, we studied the strategies for translating the following prominent elements of these ads: slogans, cultural references, multilingualism, and songs. We also did a detailed analysis of those commercials in which transcreation of aural elements was involved.

Results

The following subsections show to what extent the main ingredients of transcreation are present in the translation of Estrella Damm advertising campaigns into English: internationalisation, envisaged from the start of campaign and combined with some adaptation to the conventions of the target language and culture; the dialogue between translators and art directors; the importance of effective and affective communication; and creativity and co-creation.

Cultural References and Language in the Mediterráneamente Campaign

As every country has its own language, cultural codes, laws, and norms, it is challenging to devise a global advertising campaign that can be adapted worldwide. Many campaigns have failed because the idea has not connected with the public in the country despite the fact it is properly translated. For Sánchez (2020), the translation of an advertising campaign should work for the ad and the brand (p. 174). Not only should the text be translated, but also its values. In the case of the Mediterráneamente campaign, the meaning of the content is multiplied when the images are put in context. As mentioned above, the campaigns, which repositioned the brand, focus on reinforcing Mediterranean culture and identity. By culture, we refer to “the set of values, traditions, beliefs and attitudes that are shared by the majority of people living in a country or, alternatively, in a local community that is distinguished from the rest of the national society by major traits such as language, religion, or political and legal systems” (Torresi, 2021, p. 34).

In the campaigns at issue, the scenes, values, beliefs, and attitudes transmitted are those associated with some aspects of Mediterranean culture: the landscape, the weather (sunshine), living by the sea, food, music, enjoyment, friendship, and the Mediterranean lifestyle in general. For Amenábar (Estrella Damm, 2015), the director of the Vale campaign, “to live mediterraneanly means going out, meeting people and soaking up music, cinema, theatre, exhibitions…” (para. 4). For the analysis of Mediterranean cultural references, we follow Díaz-Cintas and Remael’s (2020) classification, which distinguishes between (a) real-world cultural references and (b) intertextual cultural references (p. 203). We could say that Mediterráneamente spots contain both real-world and intertextual cultural references, as follows.

Real-World Cultural References

-

Geographic references including: (i) locations such as Formentera (Estrella Damm, 2009), Menorca (Estrella Damm, 2010), Costa Brava, El Bulli (Ferran Adrià’s restaurant; Estrella Damm, 2011), Empúries, Dalí Museum (Estrella Damm, 2016), Serra de Tramuntana, Mallorca (Estrella Damm, 2014), Ibiza (Estrella Damm, 2015), Mediterranean beaches with pines (Estrella Damm, 2018); (ii) animal and plant species like Mediterranean fish that appear in a number of spots.

-

Ethnographic references including: (i) food and drinks such as paella (Estrella Damm, 2010, 2013), Mediterranean prawns, Spanish omelette (Estrella Damm, 2017), ensaïmada (a typical pastry from the Balearic Islands) (Estrella Damm, 2016), and, in most commercials we can see images of Estrella Damm beer (with the insert “the beer of Barcelona”); (ii) objects such as avarques (typical sandals from Menorca), Menorquina boats (Estrella Damm, 2010), porró (a special container for drinking wine) (Estrella Damm, 2014a); and (iii) culture such as the bands Love of Lesbian (Estrella Damm, 2014b), the Vaccines (Aires de Bares, 2014), and the cook Ferran Adrià (Estrella Damm, 2011).

Intertextual Cultural References

Intertextual cultural references, especially overt intertextual allusions, can be found in these spots. There are explicit references to the bands Gorillaz and Pet Shop Boys and the films Antes de Amanecer [Before Sunrise;Linklater, 1995] and Training Day (Fuqua, 2001) (in Estrella Damm, 2015). These are part of the shared cultural background between Spain and the UK, which can be understood by both audiences.

Transferring Linguistic and Cultural Elements

Since the beginning of the Mediterráneamente campaign in 2009, the ads have been run in the UK. Still, Estrella Damm’s marketing strategy in the UK has changed over the years between 2009-2021 and has been slightly modified in Spain. The first commercials (from 2009 to 2014) did not have any dialogue or text except for the slogan at the end of the film and the name of the campaign. Only songs in English could be heard, which made internationalisation easier. For example, a version of the ad Formentera (2009) was launched in the UK, primarily on Channel 4 (during the summer) although outdoor marketing, cinema advertising, and sponsorship of Spanish independent films were also used (Joseph, 2012). Notably, the slogan, the only written message in the Spanish version, lo bueno nunca acaba si hay algo que te lo recuerda was translated as “Good times never end if there’s something to remind you of them”. Hence, following Zabalbeascoa and Arias-Badia’s (2021) classification of translation techniques for subtitling (p. 370), we could say that rewording (which affects lexicosemantic features) was used; for instance, lo bueno [good things] was translated as “good times”. Plus, the song Summercat by Billie the Vision & the Dancers was a great success. Villar describes it as a temazo [a great song] that was suggested by a woman working at the advertising agency (Interview, Villar, October 4, 2021).

The following campaign (Estrella Damm, 2010) was very similar but was recorded in Menorca and the story took place in Sant Joan (Saint John) festivities. The song for that ad was Applejack by the Triangles. The slogan A veces lo que buscas está tan cerca que cuesta verlo [sometimes what you are looking for is so close that it is hard to see] was translated as “Sometimes what you are looking for is closer than you think”, is not written on screen but can be heard in the translated version. Again, rewording occurred. The verb “see” was changed to “think”.

In the summer of 2011, another commercial was aired in Spain directed by Isabel Coixet. Unfortunately, it was banned in the UK by the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) because “it was deemed ‘irresponsible’, for showing people running for a dip in the ocean right after drinking some lager” (AdAge, 2011). The ad, set on the Costa Brava (north of Barcelona), was about a man who takes part in a cooking course at the famous restaurant El Bulli of prestigious chef Ferran Adrià. We see images of this man with his friends riding motorbikes, swimming, snorkelling, and dancing on the beach. In the ad, cultural Catalan sites and elements are shown such as the Empúries ruins, the Dalí Museum, and Dalí’s moustache.

In 2015, the commercials became short films and dialogues were included. This was the case of Vale (Estrella Damm, 2015), Las pequeñas cosas (Estrella Damm, 2016), La vida nuestra (Estrella Damm, 2017) and Alex & Julia (Estrella Damm, 2018). In 2019, there was another change in Estrella Damm’s communication strategy to raise awareness about the environmental emergency in the oceans and climate change. The company decided to keep on focusing on the Mediterranean sea but from a sustainable point of view, which resulted in a group of commercials that call for action on the Mediterranean pollution: Act I. Soul (Estrella Damm, 2019), Act II. Lovers (Estrella Damm, 2020) and Act III. Commitment (Estrella Damm, 2021).

The word Mediterráneamente, which appears at the end of all commercials just below the Estrella Damm logo, has not been translated in the English version. For Tony Gray, the Spanish-English translator of Estrella Damm since 2015, “globalisation has homogenised European and global culture, so there is no need to translate some cultural elements that needed to be translated in the past” (Interview, Gray, February 8, 2022). Everybody is supposed to know about the Mediterranean diet, olive oil, good food, and the Mediterranean coast and this is a trend in most of the commercials analysed. Cultural elements such as the traditional Catalan dish suquet (fish and shellfish soup/stew) that appears in The Little Things (Estrella Damm, 2016) has been kept in the English subtitled version. Note, however, that occasionally the translation provides more information about a particular cultural reference. For example, in The Little Things (Estrella Damm, 2016), la mejor gamba roja de aquí [the best red prawn from here] has been translated as “the best Mediterranean prawns”. Whether cultural references have been translated or not, what all commercials in the Mediterraneámente campaigns have in common is the representation of the Mediterranean cultural values, which is perceived by both local and international audiences.

Multilingualism

The Vale commercial (Estrella Damm, 2015) makes use of global identity and local culture by code-switching English with Spanish (in the Spanish version) and English with Catalan (in the Catalan version). As stated above, the Mediterráneamente campaigns play a different role locally and abroad and the use of two languages in the same commercial reinforces this. As Gore (2020) puts it,

for a British audience, the use of Spanish (combined with scenes of the Mediterranean) enables advertisers to mobilise the positive associations of the corresponding stereotype [while for the home audience] [...] English signals ‘cool’ for the upwardly mobile or those that aspire to be so (p. 13).

In the short film Vale, the presence of multilingualism-or “third language” (L3) as used by Corrius and Zabalbeascoa (2011, p. 114)-is part of the plot and does not seem to be a problem for the local or the British audience. In the Spanish version, when Víctor asks Claudia if she would like a beer, she answers vale and David repeats vale. At this stage, vale has not been translated into the English version because the meaning of this word will be part of a later conversation. Víctor then approaches Rachel and Toni who are cooking. As Rachel only speaks English, most of the dialogue is in English and, consequently, it has not been translated into the target text. Only the sentence uttered in Spanish Víctor, anda, ¿me ayudas a poner la mesa? has been subtitled as “Víctor, come on, can you help me set the table?”. Víctor’s answer ¡Vale! is interesting because Rachel asks “What’s vale? What does it mean? Everybody is always saying vale, vale, vale”. Víctor answers, “Vale is for todo” [Vale is for everything] and Toni clarifies: “It just means ok”. The mix of English and Spanish in this dialogue about the meaning of the word vale is the same in the Spanish and English versions. Table 2 illustrates a similar phenomenon in another scene, in which the characters are all at the table about to start lunch.

Table 2

Vale. Gays/Guys

Only a few sentences in Spanish have been translated into English. The rest of the sentences in the ST, which are in English, are left untranslated in the TT. When this happens, the foreign language cannot be differentiated from the TT main language. Therefore, language variation becomes invisible to the TT audience (Corrius & Zabalbeascoa, 2011, p. 125).

Yet, this lack of L3 visibility has been compensated for by keeping some sentences in Spanish in the TT. Note, for instance, the scene when they arrive at the port. There is a conversation in the original version in which there is constant code-switching between Spanish and English, which has been transferred in an unchanged way:

A further point needs to be made in this analysis as there is a scene in which multilingualism has a humorous effect in the ST (see Table 3). Víctor (who does not speak English) is walking along the streets in Ibiza while thinking about what he is going to tell Rachel. He is trying to translate into English what he would like to tell her. For the Spanish audience, this scene is very funny as Victor is making Spanish words sound English.

Table 3

English not my forte

However, keeping the same invented Spanglish L3 in the TT, as in this example, does not necessarily entail that it has the same effect in the target audience, particularly, if they do not know any Spanish.

Multilingualism is also present in The Little Things (Estrella Damm, 2016), but here the third language is represented through the French accent of actor Jean Reno. In this clip, the type of language variation used would be the “dialectal meme” as it denotes “all the connotations associated with an individual or character due to the accent that features in his or her speech” (Hayes, 2021, p. 5). The subtitles provided for the English version do not mark any type of language variation, as is common in subtitling.

Language variation through accent is also present in Alex & Julia (Estrella Damm, 2018), where we can hear a presenter speaking in Spanish with a strong English accent. In this commercial, the dialogues are in Spanish and the lyrics of the songs are all in English. As Díaz-Cintas and Remael (2020) state, “linguistic accents and pronunciation are problematic to render in subtitles” (pp. 194) but “the degree to which language variation can be rendered in subtitles will depend, of course, on the technical constraints, on the guidelines the subtitler has received and on the socio-cultural TT context for which the subtitled production is made” (Díaz-Cintas & Remael, 2020, p. 183).

Something different can be spotted in Our Life (2017): a short film completely recorded in Spanish except for the sentence “arrivederci boys” (a mixture of Italian and English), which was not translated into the TT. In this clip, the protagonist, Anton, moved to Amsterdam but came back to Barcelona to sell his boat. In Barcelona, he is watching a series whose main character is the detective Chad Johnson, who then appears in Anton’s dream to make him realise that he has a nice life, but should learn to live it. The translated English version mixes English and Spanish. The series that Anton is watching and the dream that he has at night can be heard in English while the rest of the dialogues are in Spanish and subtitled in English in the tt. In this case, there is much more language variation in the TT than in the ST.

Transcreating the Aural: Songs, Rhythm, and Rhyme in Mediterráneamente

Songs are a very important component of the Estrella Damm summer campaigns. The first commercial, Formentera (Estrella Damm, 2009), marked the trend for the Mediterráneamente campaign. Accort’s Try Together, 2021) (Interview, Villar, October 4, 2021). In this second case, when we asked Villar whether co-creation of music had occurred, in that the agency gave composers tips about the goal of the songs, Villar agreed, but with the following nuances: “the work and the merit are all theirs. You need a really motivated singer […] and something really cool can come out of it. When you combine these songs with the music, it can be explosive” (Villar, Interview, 2021, own translation).

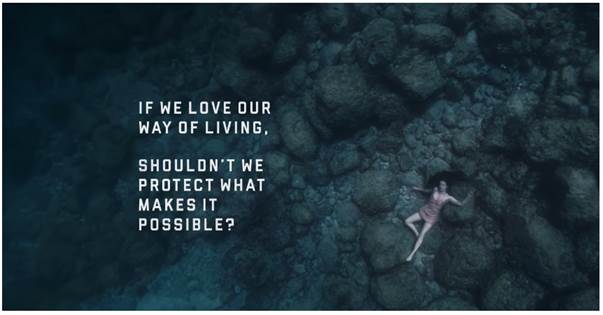

The Mediterráneamente campaign has two types of commercials, in which songs play different roles: (a) the summer commercials (2009-2018) celebrating the Mediterranean lifestyle, to which songs add a festive mood; and (b) the sustainable commercials (2019-2020) that centred on the need to preserve the Mediterranean, which is a message that is conveyed through the final slogan: “If we love our way of living, shouldn’t we protect what makes it possible?” (Estrella Damm, 2019, 2020).

Commercials broadcast between 2009-2018 included a co-branding component because Estrella Damm promoted musicians and vice versa. Songs that had not been very well-known were (re)discovered and revitalised. The promotion of music is visible in the 2014 slogan “Music is culture”, the scenery of the commercials including live concerts, and even dialogues with specific reference to music festivals, bands, and musicians. This phase closed with the 2018 commercial Alex & Julia, a celebration of the ten first years of the campaign. It includes fragments of all the songs involved in the previous commercials and closes with a new song, The Place to Stay. Songs are both the soundtrack and part of the show as the characters are singers, but the songs are not subtitled keeping with the usual criterion of translating only plot-relevant songs; just intralingual subtitles were provided for Place to Stay song in the English version of the 2018 Alex & Julia commercial.

In 2019, Estrella Damm changed its communication strategy to a more social one, focusing on sustainability but maintaining the Mediterranean aspect at its core, as can be seen in a specific section of the company’s website.1 The sustainability campaign Another Way of Living, which is also a part of Mediterráneamente, was made up of three commercials: Act I. Soul (Estrella Damm, 2019), Act II. Lovers (Estrella Damm, 2019), and Act III. Commitment (Estrella Damm, 2020). As we will see in the next section, it is only in these commercials that songs are translated.

Another Way of Living

Catalan musician Joan Dausà composed Una Altra Manera de Viure (2019) [Another Way of Living] specifically for Estrella Damm. The song has three parts, which are sung, respectively, in the three commercials: Act I. Soul (Estrella Damm, 2019), Act II. Lovers (Estrella Damm, 2019), and Act III. Commitment (Estrella Damm, 2020). These were translated by Dausà into Spanish. In turn, the Spanish song’s lyrics was the source text for the songs in English, which were translated by Gray.

Villar explained why these songs were translated. According to him, “the lyrics of Another Way of Living are a key factor because music fulfils an emotional and narrative role. Therefore, it is crucial to understand its concept” (Villar, Interview, October 4, 2021). In turn, for Gray, “translating the songs is surprisingly easy. This is because the lyrics are very short”. even though he also mentioned songs as among the most creative elements in his task as a translator for Estrella Damm (Gray, Interview, February 8, 2022).

Act I. Soul (Estrella Damm, 2019)

The commercial consists of a subaquatic dance in which Claire Friesen swims underwater surrounded by big transparent pieces of plastic at the bottom of the sea. The dancer slowly sinks to the bottom, which changes from blue to black, before closing her eyes on the seabed (Figure 1).

The images of the commercial are set against the background of Another Way of Living (Estrella Damm, 2019) sung by the same singer, Maria Rodés, in the three versions - Catalan, Spanish, and English. There are no subtitles. According to Villar, “the lyrics are key, because the music fulfils an emotional and narrative role. […] In Soul¸ it is the sea singing and asking for help, not the drowning woman”. (Villar, Interview, October 4, 2021). Table 4 shows the lyrics in Spanish and English, the language combination used by translator Gray.

When we listen to the song, we can see that there is no strict rhythmic pattern, which may explain the translator’s comments on the ease of this task. However, all assonant rhymes have been preserved. We can also see the importance of the first-person narrative, evoking the Mediterranean according to Villar, but visually personified in the figure of the dancer (Villar, Interview, October 4, 2021). There are some changes of order in the lines, probably due to production changes, but the general atmosphere of the commercial poetically conveys the perils of suffocating the sea. It is the only commercial where there are no images of Estrella Damm beer.

Table 4

Lyrics of Act I. Soul (Estrella Damm, 2019a)

Act II. Lovers (Estrella Damm, 2019b)

The English version (see Table 5) is consistent with the criteria used in Act I in prioritising a rhyming pattern, for example, in translating Con miedo y sin razón/Y apenas corazón [scared and without reason/and barely with heart] (Figure 2). In its rendering as “sailing in the dark/looking for my heart”, the metaphor sailing/searching is in keeping with the visuals: the ships and boats of several NGOs involved in environmental preservation that are portrayed in the commercial (Figure 2). Activists are shown saving turtles and dolphins, cleaning litter from the seabed, preserving Posidonia, and enjoying themselves and resting with a bottle of beer.

Table 5

Lyrics of Act ii Lovers

Act III. Commitment (Estrella Damm, 2020)

The series of Another Way of Living commercials end with the third stanza of the song in the commercial Act iii. Commitment. There are sung versions in Catalan and Spanish. In the English commercial, subtitles in English are available while the song is sung in Spanish.

The images show groups of contemporary dancers and eco-activists collecting plastic from the sea and protecting endangered birds. Figure 3 portrays a connection between humans and nature with a mixture of poeticism and activism: action and angry gestures from ecowarriors. There is an interplay of visuals and lyrics: “thousands like you”, the appeal to the earth or nature as “mother”, and the action (“gesture”) that “suddenly stops time” (see Table 6).

The graphic design of the slogans in all versions of the commercials is the same in the three languages. The only untranslated element in the English version is the slogan Mediterráneamente, which appears in Spanish.

Table 6

Lyrics of Act III. Commitment

Let’s Try Together (Estrella Damm, 2021)

This last commercial combines the festive summery atmosphere of the first Mediterráneamente commercials (2009-2018) with the eco-friendly message of the latest commercials in Another Way of Living (2019-2020). It is a playful homage to Spanish Golden Age theatre from a twenty-first-century perspective. It is set, like all the other commercials, on a Mediterranean beach. The dialogue imitates a comedy of errors, playing with the “guy meets girl” scheme, where the girl does not choose the “heartthrob” but a volunteer who is clearing plastic and litter from the sea. In a metafictional framework, a big red curtain is drawn over the beach to signal the end of the performance. The curtain rises again on a real theatre stage, where the previous scene-beach included-is reproduced and the actors and singer bow at the end of the performance and commercial. The baroque style of the whole mise-en-scene is reflected in the rhyming pattern of the dialogue.

For translator Gray, the balance between rhyme and content was a special challenge that is common to songs and poems: “You have to make it rhyme without straying away from the meaning or the content. But sometimes you have no choice”. (Interview, Gray, February 8, 2022)

He gave the example of the following lines:

Initially, he had translated pesimista as “contrite” (to make it rhyme with sight). However, advisors at the London Estrella office asked him to change this word as it is not common in British English. He replaced it with “uptight”:

Gray pointed out another example that, for him, epitomised the challenges of audiovisual translation (Interview, February 8, 2022). The name of a boat (Greta) is mentioned in the dialogue and shown on screen, and it rhymes with tableta in reference to abdominal muscles:

[Then I’ll catch a scorpion fish/If Neptune respects me/But… do you know what, guy?/ Fate brought me to Greta/ and to you/ good abs.]

This involved some changes to keep the rhythmic pattern and to convey the playful combination of classic and contemporary registers:

Another important aspect is that this commercial has a song specifically composed by a well-known singer, Rigoberta Bandini. The song is sung in Catalan and Spanish in the respective versions. In the English version, the song is sung in Spanish and not subtitled, following the same criterion as the festive summer commercials (2009-2018).

Table 7 shows excerpts from the Spanish and English versions of the rhyming dialogue. Even though subtitles do not include character names, they have been added here for clarification. Emphasis is added to the examples discussed above, and to the vocabulary that marks a contrast between classical theatre and contemporary twenty-first-century word choice. In the Spanish version, the anachronistic mentions of Insta(gram) or the Anglicism “crush” produces a comical effect.

Table 7

Subtitles of Let’s Try Together (Excerpt)

Conclusions

Even though the boundaries between the concepts of translation and transcreation are controversial in translation studies, there is an agreement that the main ingredients of transcreation are present in translation. There is agreement among specialists and scholars that the label transcreation is increasingly used, and this label has specific positive consequences for translators, such as higher specialisation and remuneration, and the explicit brief for freedom in translation. Among the key factors in transcreation, the following have proven to be relevant in translating Estrella Damm advertising campaigns into English: internationalisation, envisaged from the start of campaign; the dialogue between translators and art directors; some adaptation to the conventions of the target language and culture; the importance of effective and affective communication, and creativity and co-creation.

From our analysis of Estrella Damm’s Mediterráneamente campaign we could say that commercials can be divided into four groups: (a) Commercials with no dialogue (2009-2014): there is only music (with the lyrics in English) and a Spanish slogan at the end. Only the slogan was translated into English for the British market. (b) Short films with a lot of dialogue (from 2015-2018): these ads are much longer (between 10 and 16 minutes) and they all have a mixture of languages in both the ST and the TT. The frequency of the third language varies depending on the language and commercial. Different translation solutions have been used that range from omitting the third language in the TT (L3 invisibility) to clearly highlighting the third language in the TT. In the latter case, the presence of the third language is sometimes much greater in the TT than in the ST. This is the case of La vida nuestra/Our Life (Estrella Damm, 2017).

Apart from the difficulties posed by the translation of an advertisement, Estrella Damm translators are faced with other challenging problems, that can be found in groups 3 and 4, where transcreation was foregrounded: (3) commercials with rhyme, as we have seen in Let’s Try Together (Estrella Damm, 2021), and (4) ads where the lyrics are relevant to convey the sustainability message, as shown in Act I, Act II, and Act III (Estrella Damm, 2019, 2020, 2021). Song translation is an example of language creativity, along with attention to visuals, according to Estrella Damm’s English translator. Transcreation, therefore, might not be “another way of translating” (paraphrasing Estrella Damm’s slogan “another way of living”) but an integral part of translation even if it emphasises its added value in the translation industry (Pedersen, 2014). In sum, we might say that Estrella Damm campaigns (Estrella Damm, 2009-2021) were conceived taking into account their international distribution, where translation plays an important role.