1. Introduction

Translation is a hot topic, though views on what translation is and should be have never been more polarized. On one extreme we have Google Translate, which eight years ago posited that statistical machine translation (SMT) was capable of using big data to bypass challenges of linguistic comprehension (Sarno, 2010) and now claims that its neural machine translation (NMT) can bridge the gap between human and machine translation (Wu et al, 2016). Meanwhile, literary translation theory has gone to the other extreme, focusing on the “untranslatable” (Apter, 2013, Lezra, 2017) as a political gesture against the homogenizing sweep of globalization.

I survey recent developments in translation theory and machine translation to propose a rereading of Roberto Arlt’s Los siete locos (1929) and Los lanzallamas (1931) through the prism of translation. To reconceive Arlt-a working-class Argentine writer best known for his self-mythology as an elementary school dropout-as what Rebecca Walkowitz calls “born translated” (Walkowitz, 2015) can destabilize the polarity of the field, which tends to face global north, with English as the native language of ideas.

I focus on two “translation machines” at work within the novel: the Revolution and Arlt’s literary language1. Finally, I address how these translation machines can help us read the ending of Los lanzallamas not as a depressing farce or nihilistic tragedy but as a problem of translation.

2. Literary Translation Theory and Machine Translation

Over the last twenty-five years, we can trace a genealogy of translation theory that has taken up Gayatri Spivak’s call for translation to serve as a linchpin between “the quality and rigor” of Area Studies and “the traditional linguistic sophistication of Comparative Literature” (Spivak, 2003, p. 14). To those who would suggest that “attention to the languages of the Southern Hemisphere is inconvenient and impractical,” Spivak writes in Death of a Discipline: “The only principled answer to that is: ‘Too bad.’ The old Comparative Literature did not ask the student to learn every hegemonic language; nor will the new ask her or him to learn all the subaltern ones!” (2003, pp. 16-7)

In 2005, a special issue of Comparative Literature was dedicated to “Responding to the Death of a Discipline: An ACLA Forum.” Both Emily Apter and Eric Hayot provided close readings of Spivak’s text in relation to a matter to which Spivak herself gave short shrift: digital culture. After considering repeated metaphors of cutting and pasting and, finally, a literal repetition of two sentences in a row at the start of the long parenthesis that ends the book, Hayot concludes that “Spivak remains, throughout her book, quite critical of digital culture’s limitations, suspicious of its epistemological claims and the inequalities of its power […] And yet: the ‘i’ moves, or seems to, on the back of a metaphor whose most literal referent is Spivak writing at a computer. Cutting and pasting; a typo; teleiopoesis” (Hayot, 2005, p. 224).

Apter finds a different repetition at the end of Spivak’s brief reading of Diamela Eltit’s 1988 novel The Fourth World [El cuarto mundo]: “a self-citation” from Spivak’s 2000 essay “Translation as Culture”:

This shuttle metaphor leads, as we have already noted, in the direction of “cultural translation,” but it also swings out onto a path leading to a theory of what might be called programmed or informatic translation […] In what is a rather surprising turn in her work, Spivak, drawing on the work of Melanie Klein, takes up the idea of programmed thought. Here, translation performs the heavy work of formatting the mind-as-computer, becoming the name for the yes-no, on-off, good object-bad object choice that coincides in digital program [sic] with the alternance between ones and zeroes. […] Spivak’s speculations about the nature of programming-as a violent shuttling of cultural translation, as a violent shuttle of mind-are rife with implications for the future of translation studies and for the afterlife of a discipline called Comparative Literature. In setting up the conditions for a rapprochement between two orders of knowledge often kept separate-the cultural and the technical-Spivak establishes the terms for imagining a politics of cognition and linguistic expressionism that positions Comparative Literature center stage (Apter, 2005, pp. 205-6). Apter positions the shuttle as a master trope of Spivak’s translation theory and also a metonym for computer programming-“a violent shuttle of mind”-linking what Hayot had already noted as an interdisciplinary “shuttling between Area Studies and Ethnic/Cultural studies” (Hayot, 2005, p. 225) with an electrical metaphor: “the most immediate short circuit that a comparativist universalism might trip” (Spivak, 2003, p. 57).

Translation theory acknowledges its own paradoxical polarity: in Apter’s words, “Nothing is translatable” and “Everything is translatable” (Apter, 2006, p. 8). Jacques Lezra emphasizes a different-though perhaps analogous-polarity between a view of translation as “instrumental” vs. “aesthetically-inflected” and an imaginary balance or ratio between them: “In this imagining and remarking we establish the genealogy of the concept and practices of translation and we globalize the ecology and the market in which these concepts and practices obtain” (Lezra, 2018, p. 4).

Furthermore, Kwame Anthony Appiah had pointed to this paradox twenty-five years ago: not only is interlingual translation never able to “find ways of saying in one language something that means the same as what has been said in another” but notions of a translation’s adequacy thus “inherit the indeterminacy of questions about the adequacy of the understanding displayed in the process we now call ‘reading’-which is to say that process of writing about texts which is engaged in by people who teach them.” Appiah thus recommends “thick translation”-“‘academic’ translation, translation that seeks with its annotations and its accompanying glosses to locate the text in a rich cultural and linguistic context” (Appiah, 1993, pp. 816-7).

I have yet to read a contemporary translation theorist who disagrees with Appiah-so where are all the thick translations of Latin American texts into English? Why do we have translation theory that makes reference to Latin American literary writers and theorists, yet the consumption of English-language translations of Latin American texts-from The New York Review of Books to world literature classrooms-rarely addresses the cultural or literary specificity Appiah demanded a quarter century ago?

In fact, Latin American writers, cultural critics and theorists have considered translation a key theme and modus operandi for at least a hundred years. In the words of Edwin Gentzler, literature “reciprocally informs the field of translation studies. Translation in South America is much more than a linguistic operation; rather it has become one of the means by which an entire continent defines itself” (Gentzler, 2008, p. 108). Marietta Gargatagli goes so far as to call translation “la definición misma de la literatura argentina [the very definition of Argentine literature]” (Adamo, 2012, p. 10).

The polarity inherent in translation was already central to the 19th and early 20th century debates on national language. Borges published his own tongue-in-cheek essay on the topic, “Las dos maneras de traducir,” in 1926: “Universalmente, supongo que hay dos clases de traducciones. Una practica la literalidad, la otra la perífrasis. La primera corresponde a las mentalidades románticas; la segunda a las clásicas. [Universally, I suppose there are two classes of translations. One practices literalness, the other paraphrase. The former corresponds to romantic mentalities; the latter to classical ones] (Borges, 1926, p. 2). Being Borges, he both convinces us of this distinction and deconstructs it via a series of examples from Martín Fierro, showing how translation not only fails to be one or the other, but also obfuscates the translation internal to the original Spanish. Aníbal González has theorized this view of translation as double bind:

Translation, like incest, leads back to self-reflexiveness, to a cyclonic turning upon one’s self which erases all illusions of solidity, all fantasies of a ‘pure language’, all mirages of ‘propriety’, and underscores instead language’s dependence on the very notion of ‘otherness’, of difference, in order to signify ‘something’, as well as the novel’s similar dependence on ‘other’ discourses (those of science, law and religion, for example) to constitute itself […] (González, 1987, p. 76)

In dialogue with Derrida and Benjamin, González points to “all literature’s origins in translation” (1987, p. 77). Even as we reclaim the “untranslatable,” we must remember that it is the fantasy of the untranslated that is the lie, at least in Latin America.

For this reason, there is an important argument that much of the work of thick translation may have been done by Latin American writers before a single word was translated into interlingually. Rebecca Walkowitz coined the term “born translated” for texts in which “translation functions as a thematic, structural, conceptual, and sometimes even typographical device” (Walkowitz, 2015, p. 4).

A darker aspect of this reality-which exceeds the scope of this essay-is the notion that texts requiring thick translation are neither marketable nor profitable. In the age of big data, we have the promise of immediate, free translation through Google Translate, bypassing cumbersome syntactical rules-and comprehension-entirely. Built to aggregate millions of examples of existing translations around the web, Google Translate “(is) correlating existing translations and learning more or less on its own how to do that with billions and billions of words of text […] In the end,” says former leader of Google’s machine translation team, Franz Josef Och, “we compute probabilities of translation” (Schultz, 2013).

In 2016, Google announced that it was further improving on statistical machine translation with Google Neural Machine Translation, which was capable of “deep learning” to improve accuracy (Le & Schuster, 2016). Yet it’s important to remember that the term “deep” is quantitative, rather than qualitative. In the words of Douglas Hofstadter:

When one hears that Google bought a company called DeepMind whose products have “deep neural networks” enhanced by “deep learning,” one cannot help taking the word “deep” to mean “profound,” and thus “powerful,” “insightful,” “wise.” And yet, the meaning of “deep” in this context comes simply from the fact that these neural networks have more layers (12, say) than do older networks, which might have only two or three. But does that sort of depth imply that whatever such a network does must be profound? Hardly. This is verbal spinmeistery (Hofstadter, 2018).

As any college undergraduate has discovered, Google Translate works fairly well with conventional translation between major languages. However, as we might infer from Google Translate’s statistical definition of depth, it does not do well with the peculiar, what Google calls “rare words.” Google Translate handles “rare words” by reducing them to their more common constituent “wordpieces” (Wu et al, 2016), which may or may not be etymologically relevant to the source language.

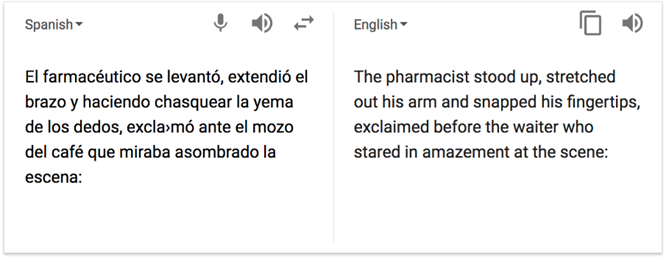

I can illustrate this easily by contrasting two consecutive sentences from Los siete locos: They occur at the end of the third chapter, when Erdosain has begged Ergueta, the pharmacist for money to pay back what he has stolen from the Sugar Company. In response, “de pronto ocurrió algo inesperado [something unexpected happened]”:

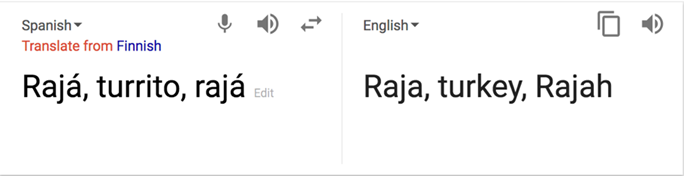

Google Translate was able to approximate the first sentence, including “chasquear la yema de los dedos” (though “snapped his fingers” would be more idiomatic). However, the lunfardo “rajá, turrito, rajá”-a line I have celebrated since the first time I read it twenty years ago-is not “big” enough for big data. There aren’t enough examples on the internet for the decoder to find a likely equivalent for this sentence-or any sentence at all.

It’s easy to make fun of machine translation. Without rule-driven grammar, Google Translate wonders if the phrase is in Finnish, doesn’t realize that rajar is a verb, let alone a command, and of course bypasses meaning entirely. It doesn’t know what rajar means either in standard Spanish or in lunfardo, and certainly not that in this case it means “scram!”2 We can imagine why Google Translate finds “Rajah”-a sovereign of the British Raj-but gives no explanation for why it would translate the same word as the nonexistent “Raja” the first time it appears.

However, the turkey is my favorite part of this translation. Imagine the “wordpieces” that would give us “turkey” from “turro”-for a machine unrestricted by even the concept of linguistic or national boundaries, why not find that “tur” suggests “turkey”? And here we come full circle to something uncanny: taken in its U.S. slang usage, turkey was used in the 19th century to describe frank, mutually beneficial business talk-hence “to talk turkey-; in the 1920s it was used to describe a theatrical or cinematic flop; and by midcentury it came to mean “a stupid, slow, inept, or otherwise worthless person” (Murray, Bradley et al, 1989, p. 691). Of course, none of this interests Google Translate-its premise is that big data’s bigness obviates the need for meaning. Hence the uncanny feeling that Google Translate-for reasons beyond my comprehension-may well have come up with a fair translation of turro, defined variously as inept, stupid and malignant, un “individuo sin mayores alcances [an individual who hasn’t achieved much]”; “haragán [bum, idler]”; “persona crédula y a la vez codiciosa [a person who is both gullible and greedy]” (Rodríguez).

The implications of machine translation for minor languages and literatures are-despite assurances to the contrary (Sarno, 2010) -pretty dire. Yet I find something liberating in machine translation, in the way it exposes the inadvertent, often inept and always defamiliarizing associations that also underlie how slang and literary language create new worlds. If we take up Lezra’s proposal that machine translation has always “spidered away at natural languages” (Lezra, 2018, p. 5), then perhaps machine translation also inheres in literary language.

Rather than demonizing machine translation in contrast to the theoretical rigor of a theory of “untranslatables,” rereading literatures through the lens of translation allows us to elude equivalence while finding solidarities, joining rebellions across time and place, language, medium and imaginary. Rather than finding a universal ghost in the machine, rereading Arlt in the context of the contemporary translation debate can reveal the machine in the ghost.

3. Translation Machines in Los siete locos and Los lanzallamas

Roberto Arlt is known for being a writer of “porteño” rather than formal Spanish, for being the rebellious “autodidacta, reacio a la escolarización y expulsado de la escuela primaria” (Saítta, 2013, p. 132). In humorous autobiographical sketches, Arlt admitted to spelling errors and bragged about being the first Argentine writer to have sold a story at the age of eight (Arlt, 1931; Arlt, 1926), exaggerating the circumstances of his life in a way that encouraged critics to identify him with his downtrodden protagonists (Saítta, 2000, p. 10). He wrote contemptuously that he didn’t have the time or money to “do style” (Arlt, 2000, p. 285).

In fact, as Saítta, Mariano Oliveto and Fernando Rosenberg make clear, despite his outsider image, Arlt intervened in debates on literary language in Buenos Aires in the 1920s and created a style that bridged literature and newspaper, street and salon. “[E]scribe en “porteño”, porque así es la única forma de dar cuenta de la realidad que representa en sus textos [he writes in Porteño, because that is the only form that can tell the reality he represents in his texts]” (Oliveto, 2016, p. 309-10); but he simultaneously “eleva el idioma de la calle, la lengua plebeya, a idioma nacional consolidando simultáneamente un lugar de enunciación dentro de las páginas de un diario y un lugar de enunciación, una entonación, dentro de la literatura argentina [elevates the language of the street, the plebeian tongue, to a national language consolidating simultaneously a place of enunciation within the pages of a newspaper and a place of enunciation, an intonation, within Argentine literature]” (Saítta 2005). Fernando Rosenberg sees Arlt’s narratives as “enunciations from and about a global, simultaneous dynamic. This concern with positionality implies that the division between margins and centers, although unavoidable, is always in the making, continually reformulated, reinforced and contested” (Rosenberg, 2006, p. 16).

I propose that we can read Arlt’s stylistics of industrial design as a translation factory, full of machines running pell mell, frequently breaking down and then reintegrating broken meanings. Arlt’s aesthetics of industrial automation is half chop shop, half custom, stripping stolen phrases for parts and assembling insane low riders with eyeball gearshifts and rocket engines, fulfilling a fantasy of unceasing production.

This mad metonymy factory works at every level of language and plot, preventing a fully resolved metaphorical interpretation at the end of Los lanzallamas. Concatenating associations take us from copper rose to rose-gold, to the red fog of a brothel, to the coppery fog of beard on Barsut’s face, to Barsut’s coin-becoming, murdered (Erdosain thinks, wrongly) to finance the Revolution, to the taste of copper sulfate in Erdosain’s mouth when he murders La Bizca, constructing a metastable textual alchemy whereby particular elements come together in free-association, elective affinities whereby copper is variously red, golden, rose or green; a gas, a metal, a liquid; “where the mass-production of the rosa de cobre will finance the cúpulas de cobre rosa (rose-copper cupulas) of the Revolution’s new City for Kings” (Solomon, 2014, p. 73).

There are many ways translation operates in Los siete locos and Los lanzallamas. “Big ideas” of 1920s Buenos Aires intellectual life from cinema, economics, science and philosophy flow through the novel, lost and found, cited and distorted, translated between languages and from books into slang) in a perpetual remix of high and low, inside and out. The Astrologer’s ideas-particularly his uses and abuses of philosophy and economic theory-have been amply studied by scholars, as has Erdosain’s scientific knowledge3. I want to suggest that by considering two of them-the Astrologer’s Revolution, as a machine operating primarily at the level of plot, and Arlt’s literary language, which operates at every level of the novelas “translation machines,” we can extrapolate a dynamic that is also present in other aspects of the novel, whereby every translation machine also presupposes machine translation.

The first translation machine I want to consider here is, therefore, Arlt’s literary language, which has been summarized as “porteño” but which I argue contains “porteño” but exceeds it. The “porteño” spoken in the novel certainly brings in the heteroglossic cosmopolitan city: Arlt wrote a city of outsiders in a decade rife with debates over national language, a city in which close to half the population was foreign-born, and most of whom spoke a language other than Spanish (Censo Nacional, 1914, pp. 201-2). Yet as much as Arlt’s literary language is regionally (we might say municipally) distinctive, it also exceeds monolingualism, resonating with Derrida’s repeated assertion in Le monolinguisme de l’autre, “Je n’ai qu’une langue, or ce n’est pas la mienne [I only have one language, which isn’t mine]” (Derrida, 1996, p. 16).

Aside from occasional eruptions by peripheral characters, we don’t see much switching between languages in the novel, but characters code-switch within Spanish. The language that prevails is the “porteño” Arlt defends in “El idioma de los argentinos” (1930), in which he proclaims that a so-called “pure” language produces texts “tan aburridores, que ni la familia los lee [so boring, not even the family reads them]” (Arlt, 1933). And yet the “gramáticos” [grammarians] Arlt mocks were themselves translators: they were not threatened by interlingual translation, but by “linguistic relation that has undergone a process of mediation through a foreign and not prestigious language,” such as the “shallow jargon infested by italianisms” (Sarlo, 2014). It was Arlt’s literary use of “porteño” that made the major language crier un cri [cry out] (Deleuze & Guattari, 1975, p. 44). Had Arlt written exclusively in “porteño,” he would not have revolutionized literary language. It is his veering among different registers, his ironic juggling of lunfardo and scientific jargon, philosophy and brute violence that rebounded on all concerned, inside and outside the novel.

When Erdosain dreams he is engaged to one of the daughters of Alfonso XIII, King of Spain (1886-1931), Arlt moves fluently from standard Spanish to Castilian Spanish to an exaggerated expressionistic imitation of Castilian Spanish and back to Erdosain’s usual informal register:

Sabía que era novio de una de las infantas. Este suceso acompañado del hecho de ser lacayo de su majestad, Alfonso XIII, le regocijaba inmediatamente, pues los generales le rodeaban, haciéndole intencionadas preguntas. Un espejo de agua mordía los troncos de los árboles siempre florecidos e blanco mayor, mientras que la infanta, una niña alta, tomándole del brazo, le decía ceceando:

Erdosain, echándose a reír, le contestó con grosería a la infanta: un círculo de espadas brilló ante sus ojos, y sintió que se hundía, cataclismos sucesivos desgajaron los continentes, pero él hacía muchos siglos que dormía en un cuartujo de plomo en el fondo del mar (Arlt, 2000, p. 106, emphasis mine).

[He knew he was the lover of one of the Infantas. This together with the fact that he was Alfonso XIII’s lackey amused him immediately, since generals surrounded him, asking suggestive questions. A mirror of water bit the trunks of the trees always in flower in white major, as the Infanta, a tall girl, took him by the arm, and said, lisping:

Erdosain, bursting out laughing, answered her crudely: a circle of swords shone before his eyes, and he felt that he was falling, successive cataclysms broke apart the continents, but he for many centuries had slept in a little room made of lead at the bottom of the sea].

Multidirectional irony erupts, initially directed at Castilian, but ending up hitting Erdosain as well. Any translation of this dream into English will lose some of this, beginning with the word novio, which juxtaposes a contemporary colloquial usage of the word for “boyfriend” to the stuffy term infanta for a Spanish King’s daughter. This juxtaposition is irreverent because “el novio de la infanta” would normally refer to the infanta’s fiancé; here the infanta is sleeping with her father’ servant. There is no adequate equivalent of pues in this instance, to convey the delay and build up to Erdosain’s laughter. Though used in Argentina more in the 1920s than today, the correctness of “pues” prolongs an ambiguity about what amuses Erdosain here, and why, so the situational irony can boomerang on him: being the infanta’s lover and her father’s lackey is initially amusing, until he forgets his “place” by laughing, and now the generals who were making innuendos a moment ago are ready to kill him.

The infanta’s accent can be described as a lisp, or a Castilian lisp, but that does not convey Erdosain’s contempt for her ceceo, nor does the English archaism “doth” deliver the same punchline as “amáis,” which is mocks the archaic voseo reverencial, which the infanta is using to address her inferior. The cuartujo de plomo at the end returns Erdosain not just to Argentina and low-class periphery, but to the bottom of sea, in a little lead room. This diminutive suffix connotes poverty; lead suggests sound isolation but also protection, with odd connotations of a diving bell, a cell, a mental institution.

And yet, in Arlt, as we have seen, no metal is inert, so the lead also begins its own chain of metonymic associations. Erdosain is never allowed to simply ridicule something without participating in its logic. He mocks what he longs for and longs for what he mocks. Thus a similar image reappears near the end of Los siete locos, in the chapter “El suicida [The Suicide],” when Erdosain longs to “dormir en el fondo del mar, en una pieza de plomo con vidrios gruesos. Dormir años y años mientras la arena se amontona, y dormir […] sintióse diluido como si se hallara en el fondo del mar y la arena subiera indefinidamente sobre su chozo de plomo [sleep at the bottom of the sea, in a lead room with thick windows. Sleep years and years as the sand heaps up, and sleep […] he felt diluted as if he were at the bottom of the sea and the sand rising indefinitely over his chozo de plomo” (Arlt, 2000, p. 266-7). Again the word chozo is uncommon, again the connotation is poverty. Erdosain has also used lead by analogy to men’s souls (neither can be turned to gold); his sadness is una pelota de plomo que rebotara en una muralla de goma [a ball of lead bouncing off a wall of rubber] (215).

Finally, as we shall see, lead reappears in the walls of the phosgene factory Erdosain designs with help from a technical manual. I have said that each translation machine in Los siete locos and Los lanzallamas also implies machine translation. If Arlt’s literary language is a translation machine-imbibing, mixing, producing, permutating multiple languages-the phosgene factory is a good example of its statistical aggregation, standardization and ultimate machine translation.

The Astrologer’s Revolution is the beating heart of the novel. From one angle, it amounts to a capitalist shell game: mirroring men’s dreams, the Revolution takes them for everything they’ve got. In Josefina Ludmer’s words: “El plan del Astrólogo resulta ser un “cuento” para quedarse con el dinero (los números y los cuerpos de los hombres comunes, o segundos, cuando lo han perdido todo). En ese momento les vende revoluciones a medida [The Astrologer’s plan ends up being a “story [lie; tall tale]” to keep the money for himself (the numbers and the bodies of common men, or second-rate men, when they have lost everything). In that moment he sells them custom revolutions]” (Ludmer, 1999, p. 487). The “Revolution” as such does not exist: what exists is an infinitely malleable idea of “Revolution” to fit each loco’s fantasy.

Once recruited by the Astrologer, locos articulate their (formerly inchoate and private) fantasies, and are then encouraged to channel them into “revolutionary” action. Each loco has an essentially private experience of the meaning of Revolution, from Ergueta’s apocalyptic literalist misreadings of Revelation to Haffner’s theory of pimping, through which they channel a lumpen libido untapped by society.

Although the Astrologer masterminds the Revolution (arguably in cahoots with Hipólita), his actual plan is far humbler than the ideas he sells back to the locos. As the Revolution rolls forward through the novel, as locos translate their hopes into plans and put the plans into practice, the Astrologer machine-translates the locos’ stories, dreams, and actions. Much like Google Translate, the Astrologer provides a free service-translating idle fantasies into “Revolution”-and in exchange collects user data. A truism of contemporary internet culture is that “if you aren’t paying, you’re not the consumer, you’re the product” (Oremus, 2018); and the Astrologer flatters his locos into thinking they are ideologues in a revolutionary cadre, when really he is only interested in their ideas statistically, in their utter exchangeability within the medium of Revolution. They are, as Ricardo Piglia and others have pointed out, capital (Piglia, 2004, p. 58). But they are also product development.

The genius of the Astrologer’s Revolution is that participation is entirely voluntary. By becoming part of the Revolution, Erdosain is temporarily but repeatedly freed from feelings of dread and abject powerlessness. It is both a distraction and a channel for his creative energies as an inventor. However, as many times as he is uplifted by his possible importance, he comes crashing down with intuitive doubts about the Astrologer’s plan. Halfway through Los siete locos, Erdosain demands that the Astrologer sign a confession admitting that he and Bromberg murdered Barsut, “to make sure you’re not trying to trap me.” In return, the Astrologer demands “absolute obedience” (Arlt, 2000, pp. 136-7):

Comprendía que iba en camino hacia un hundimiento del cual no se imaginaba de qué forma saldría maltrecha su vida, y esa incertidumbre así como su absoluta falta de entusiasmo por los proyectos del Astrólogo, le causaban la impresión de que estaba obrando en falso, creándose gratuitamente una situación absurda. “Todo había hecho bancarrota en mí”.

[He understood that he was headed toward a collapse and he couldn’t even imagine the ways it was going to ruin his life, and that uncertainty together with his absolute lack of enthusiasm for the Astrologer’s projects gave him the impression that he was play-acting, pointlessly [lit. gratuitamente, for free] creating an absurd situation. “Everything had declared bankruptcy in me” (Arlt, 2000, pp. 137-8).

This unpredictable relation between translation machine and machine translation-between feeling empowered and powerless-flips with Erdosain’s mood. One minute, he’s a capitalist, the next he’s capital. This iterates uncertainty for the reader, who receives little guidance from the close third-person narrator except in the form of commentator’s notes: until we learn the Astrologer’s true designs, the reader must choose to believe either that the Astrologer is systematically insane, or insanely unsystematic. How are readers to metabolize this contradiction when we discover, in the antepenultimate chapter of the novel, that for the Astrologer Revolution was a set of lures and illusions all along?

I suggest that Erdosain’s research, designs and report to the Astrologer on the design and use of a phosgene factory to attack Barrio Norte showcase his work as a translator of inventions. In this case, “este sistema de fabricación es angloamericano [this manufacturing system is Anglo-American]” (571). Erdosain also has to adapt the Disciplina de Gas [Discipline of Gas] from war to Revolution: “En un ataque revolucionario que es de sorpresa y minoría,” he clarifies, “el mejor sistema para transportar fosgeno es el camión tanque [In a revolutionary attack that is a surprise attack by a minority, the best system to transport phosgene is the tanker truck]” (Arlt, 2000, p. 575). A detailed map of the factory accompanies the report.

Readers could be forgiven for skimming the excruciatingly detailed report without much care. Yet the report, and Erdosain’s process of writing it, are structurally significant, spanning a hundred pages in the novel, and gas fills the novel from the very first pages when Erdosain’s zona de angustia [zone of anguish] is described “como una nube de gas venenoso [like a cloud of poison gas]” (10). By rereading the phosgene factory as a product of the translation machines of Arlt’s literary language and the Astrologer’s Revolution, a metatextual nexus, we can elude the novel’s unhappy ending.

The chapter called “El enigmático visitante [the enigmatic visitor]” begins with a six-page flashback to Erdosain at the age of seven, when his only relief from his father’s abuse was building and destroying “fortalezas [fortresses]”. Ironically, as Erdosain wakes up, he finds a soldier sitting on his bed, in full trench gear of a poilu [French infantry soldier], wearing a gas mask, gloves and carrying a German pistol, and slowly dying of gas exposure.

The soldier argues with him about the ethics of using gas- “caerían inocentes [innocent people would die]” (483)-though first he criticizes the specific choice of phosgene, recommending lewisite instead (481). He also rants about the percentages of Green Cross and Blue Cross gas that were used in attacks.

However, as Erdosain prepares his report on phosgene gas for the Astrologer, he never once thinks of his strange visitor. Instead, he pages through L’enigme du Rhin, a French translation of Victor Lefebure’s The Riddle of the Rhine (1919). Though the book appeared in Spanish in 1923 (El enigma del Rhin), Erdosain reads it in French, translating the percentages of Green Cross and Blue Cross gases that Germany used. The percentages make him smile-he has already heard them from the gaseado, though he doesn’t remember-and he falls into a long daydream about a glass torpedo operating as a Croockes cathode-ray, firing green light that destroys everything in gruesome detail. In translating the French translation of an English book, Erdosain transforms green gas into green light, and the lungs of the city fill up with rays from the glass torpedo. Only then does he imagine the clouds of gas, and as he writes down the statistic-90% lethality-he transposes the horrors of World War I to Barrio Norte:

Una frase estalla en su cerebro: Barrio Norte. La frase se completa: Ataque a Barrio Norte. Se alarga: Ataque de gas a Barrio Norte.

A phrase explodes in his brain: Barrio Norte. The phrase completes itself: Attack on Barrio Norte. It expands: Gas attack on Barrio Norte.] (Arlt, 2000, pp. 526-7).

Expanding in every direction, green gas in the novel is a ubiquitous metonym of the war as precisely “untranslatable”-yet war is also the original machine translation: a violent erasure of difference beneath forced equivalence.

Gas is green in Los siete locos and Los lanzallamas, though phosgene is described as “colorless gas” that may form “a white cloud” (Bast & Glass, 2009); the threat of undetectable gas was part of German propaganda in 1915 prior to using phosgene for the first time (Lefebure, 1923, p. 221). Yet the interpretation of gas attacks by the allies was limited to their translation of Germany’s color-coded system: Yellow Cross was mustard gas, the most lethal (Lefebure, p. 117); Blue Cross was less persistent but could force soldiers to take off their gas mask, which then exposed them to Green Cross gas (Lefebure, p. 237), with its “slightly persistent, volatile, lethal” phosgene compounds (Lefebure, p. 52).

Gas is also green in Wilfred Owen’s “Dulce et decorum est” (1920), one of the best-known war poems. “Dim through the misty panes and thick green light, / As under a green sea” (Owen, 1921). This reminds us of Erdosain’s wish to sleep at the bottom of the sea, particularly as he ignores the soldier and Owen’s warning to “not tell with such high zest / To children ardent for some desperate glory, / The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est / Pro patria mori” (Owen, 1921). By contrast, an overexcited Erdosain is entranced by “the poetry of the gases of war!” (Arlt, 2000, p. 486). He replies to the soldier’s descriptions of horror with glee: “¿Sabe usted que debe ser divertido ese juego atroz? [You know that atrocious game must be fun?]”; “No; no era divertido,” the soldier replies [No; it wasn’t fun] (Arlt, 2000, p. 484), but Erdosain rhapsodizes, undeterred:

¡Cruz Verde!… ¡Cruz Amarilla!… ¡Cruz Azul!… ¡Oh, la poesía de los nombres infernales! Jesús está tras de cada cruz: la Cruz Verde, la Cruz Amarilla, la Cruz Azul… Compuestos cianurados, arsenicales: … los químicos son hombres serios que contraen enlace muy jóvenes y tienen hijos a quienes les enseñan a adorar a la patria homicida.

[Green Cross!… Yellow Cross!… Blue Cross!… Oh, the poetry of the infernal names! Jesus is behind every cross: the Green Cross, the Yellow Cross, the Blue Cross… Cyanide compounds, arsenic… chemists are serious men who get tied down very young and have children they teach to adore the homicidal patria] (p. 486).

The dying soldier leans over Erdosain, comforting him, “Llorá, chiquito mío [Cry, my little one],” and Erdosain cries, consoled. Cry until your heart breaks, the soldier advises him and you love your fellow men “as much as your own pain” (p. 487). Erdosain kisses the soldier’s hands, his “broken buttons.” “Nunca,” Erdosain told the commentator later, “experimenté un consuelo más extraordinario que en aquel momento [Never did I feel more comforted than in that moment” (487). When he lifts his head, with a “superhuman peace,” the man is gone. A recurring figure in the novel is the pietà: Erdosain seeks pity above all else, to lay his head “in a woman’s lap” (Arlt, 2000, p. 218), when as a child: “le est[aba] negado hasta el regazo donde poder llorar desmesuradamente [even the lap in which to cry excessively was denied him]” (p. 469).

Nonetheless, every pietà in the novel entails mutual incomprehension under the sign of equivalence: Hipólita plans to betray him as she cradles his head and he feels her pity (p. 229). Erdosain intends to commit precisely the horrific crime the soldier has urged him against. He goes straight back to his plan. The Astrologer reads the entire report aloud, “a media voz [in a whisper],” and then abruptly leaves forever.

It is almost impossible to read this ending without reference to Arlt’s revisionist autobiography: like phosgene gas, his abusive German father, his German-speaking household in neutral Argentina exceed the parameters of self-mythology, spilling over into the main narrative of the novel. Erdosain translated an Anglo-American manufacturing system to translate a German gas attack from war to Revolution and from the Rhine to elite Barrio Norte in the heart of the patria.

Instead, Erdosain turns away from the phosgene factory, and drifts metonymically off onto a gratuitous murder-suicide, killing La Bizca with the taste of copper sulfate (blue when hydrated) in his mouth. Erdosain’s murder-suicide is foreshadowed yet it feels wrong: it’s too small for its elaborate setting, a bait-and-switch that leaves the reader feeling foolish. Such nihilism is incompatible with the novel’s wild manufacturing energies: its total pessimism rings false.

Arlt’s literary language transmutes sentiments into chemicals, pistons, and polygons, creating a whole industrial vocabulary for human feeling. The Astrologer’s Revolution analyzes and standardizes the dreams of locos in order to scam them. The phosgene factory initially exemplifies both translation machines at work; but the ending misses structural cues and flattens multidirectional irony, setting up the enigmatic visit of the gassed soldier so that Erdosain can ignore his plea, layering intertextual references to Arlt’s well-known autobiography and abandoning them, creating an entire technical manual within the last part of the novel for a factory and an urban attack only to leave it there. Would it be too much of a stretch to consider Erdosain’s murder-suicide a final machine translation-and a bad one?

4. Conclusions

Julio Cortázar wrote that “los planos y dibujos de la fábrica de fosgeno no son más que una manera de llenar con trabajo el horror de otra noche al borde del crimen [the maps and drawings of the phosgene factory aren’t anything more than a way of filling the horror of another night on the edge of crime with work” (Cortázar, 1981, viii, emphasis mine). In some sense, this is empirically true. It’s consistent with how Erdosain used the Revolutionary translation machine to channel his energies; it’s also accurate in that- ultimately-his own inventions were all machine-translated by the Astrologer into a purely fungible form, as capital. It didn’t matter if they worked, it only mattered if people “bought” the idea, thus “buying into” the Revolution.

And yet if this is a hopeless novel, why are its contents so much bigger than its conclusions? At every level of plot and language, energy is always escaping through the cracks as a sheer manufacturing jouissance hisses and percolates, permutating by metonymic assembly line, sublimating and liquifying in a continual passage from one stage to another.

This contradiction can be shorthanded (or hypostatized) in the aporetic relationship between the two halves of the novel: in the hinge from Los siete locos to Los lanzallamas. It is hardly an original observation that, among other things, the market crashed between the publication of the two halves of the novel; and I would suggest that the reader-translator is left holding a lot of worthless stock when the Astrologer’s machine translation of Revolution “triumphs” at the end of the novel. Not only did the Revolution in the mind of Erdosain (and of the reader) exceed the Astrologer’s plan, but the Astrologer’s plan in Los siete locos exceeded the Astrologer’s plan in Los lanzallamas. As a result, the novel is left overflowing, supersaturated with untested ideas, calculations and blueprints.

A peripheric “big data” is already present in Los siete locos and reaches its logical culmination in Los lanzallamas, illustrating its practical utility (and exploitability) in the Astrologer’s machine-translation of the Revolution, as he and Hipólita escape with the money. Yet Erdosain’s murder-suicide can also be interpreted as an apotheosis of what is, in the words of Hofstadter, “deeply lacking” in machine translation, and “which is conveyed by a single word:understanding:

Machine translation has never focused on understanding language. Instead, the field has always tried to “decode”-to get away without worrying about what understanding and meaning are. Could it in fact be that understandingisn’t neededin order to translate well? Could an entity, human or machine, do high-quality translation without paying attention to what language is all about? (Hofstadter, 2018).

The danger with machine translation is human: if we believe Google understands us, if we think the Revolution is for real, if we believe the Astrologer is the hero of the story, we’ve taken the bait, mistaken aggregation for comprehension, predictive algorithms for empathy. Arguably, Erdosain is dead because he was, in the end, unable to distinguish them.

Even today, nearly ninety years after the appearance of Los siete locos, Arlt’s novel both instantiates and capitalizes on contemporary contradictions of capitalism and our relationship to machines. The text is searchable yet in important ways illegible, marginalized by modernization while limning the modern. It disfigures statistical norms of language use to elude Google Translate while figuring in Google top search results. Despite the novel’s ending, its summary disposal of its own protagonist as just another victim of modern times, the phosgene factory, the copper rose, and all the infinite literary potential of Arlt’s aesthetics of industrial emotion remain in the world, a still-undetonated literature.