Introduction

Sworn translators and interpreters (STIs) are a group of professionals known also as legal or court translators/interpreters, because of their specific acting scenarios (i.e., mostly legal or governmental situations; Pym et al., 2012, p. 26). They are a worldwide recognized remunerated group of professionals (Mayoral, 2000; Monzó, 2002; Pym et al., 2012), which means that many institutions and individuals know they exist, that some laws recognize them, and that, in some cases, associations, governments, or schools regulate them (Stejskal, 2003, 2005). This recognition or authorization makes them crucial for many bilingual inter actions between institutions and governments around the world. Furthermore, it puts them in an essential position for most contacts between two cultures and languages in specific types of documents and scenarios (Mayoral, 2000). In addition, it differentiates them from other types of translators/interpreters and places them at a different level compared to other specialists in translation/interpretation (Monzó, 2002).

Given the above stated recognition of STIs, the academia, as well as associations and governments in many countries, have carried out different studies and initiatives about them. These studies and initiatives have described STIs, their behavior, their functions, and their acting scenarios and tried to understand their influence and status (Mayoral, 2000; Monzó, 2002; Stejskal, 2003, 2005). Additionally, they have made the importance of this social group in our society clear (Heras, 2017; Galanes, 2010; Vigier et al., 2013) and have helped offer better alternatives for their training, association, and regularization (Ordoñez, 2009; Ortega, 2011; Zamora, 2005). By the same token, they have explored the certification procedures (Galanes, 2010; García, 2007; Ortega, 2011; Vigier, 2010) and the historical aspects related to the activity (Feria, 2007; Peñarroja, 1989; Peñarroja & Cardona, 1993). Moreover, in Spain1, they have examined the status of STIs from sociological, market oriented, economic, as well as other points of view (Biguri, 2007; de las Heras, 2017; El Ghazouani, 2008; Gil & García, 2015; Lobato, 2007; Mayoral, 1999, 2000; Monzó, 2002; Perdu & Ridao, 2014; Salvador, 1996). Furthermore, they have contributed to the reflection about STIs in their corresponding countries which, at the same time, contributes to the reflection of translation and interpreting in general in the specific territory. Examples of this are Zamora (2005) in Costa Rica, Guzmán (2008) in Russia, Barceló and Delgado (2016) in Spain and France, Martínez and Guilman (2005), and Cortés (2000) in Argentina, Livio (2000) in Brazil, and Hlavac (2013) in Canada, among others.

Contrasting this wealth of initiatives and studies in the world related to STIs, in Colombia there are only six academic studies dealing with this segment of translators/interpreters (Clavijo, 2011; Martín, 2013; Quiroz et al., 2013, 2015). As the previous studies made in countries different from Spain, they are merely demographic or descriptive. Quiroz et al. (2013), for example, focused on defining the profile of candidates to become STIs that were more likely to pass the exam while Quiroz et al. (2015) focused on some general aspects about STIs as an occupational group. On the other hand, Quiroz and Zuluaga (2014) made a quantitative description of the performance of candidates to become STIs, while Clavijo (2011) and Martin (2013) made a description of some general issues related to the status of STIs in the law and in the practice. Thus, as can be seen, studies and initiatives on this segment of translators in Colombia have not deeply and recently explored any specific process related to their current status nor any particular reflection about the market behavior has been made.

In reality, there are very few studies around the world concerning the market behavior of sworn translation and interpretation services. Some of the main topics that have been left apart are rates, professional offers, number of translators or interpreters in organization, among others. This reality is something that can also be seen in Colombia where only some projects or initiatives have tried to carry out research projects related to market behavior and status in this segment of professionals.

Accordingly, the present article intends to present some updated reflections on the current situation of sworn translators and interpreters in Colombia and some important aspects related to market behavior, with special emphasis on directionality. Consequently, the paper aims at doing the following: (a) describe what the cur rent state of Sworn Translators and Interpreters in Colombia is; (b) describe the main aspects related to directionality in this group of professionals; (c) explain, by means of quantitative analysis, the main traits of the market in sworn translation and interpreting in Colombia; and, (d) make some general comments on the findings of this study compared to the reality of the profession of translators/interpreters in Colombia and the world.

In the following sections, the reader will find a brief description of details about STIs such as the various ways in which they are denominated, regulated, or organized in the world and in Colombia. In addition, they will find a brief summary of key aspects related to directionality principles and theories that this study will draw on. Subsequently, the reader will see the main methodological aspects taken into account for the design of this research such as participants and data gathering sources.

¶Finally, the reader will find a brief summary of the findings and general discussions and interpretations related to market behavior and directionality.

2. Theoretical Framework

This study draws on the directionality theories. Specifically, it draws on key aspects or principles within this perspective. That is why, the following paragraphs provide key aspects about the concept of directionality and, specifically, about the current thoughts, beliefs, and reflection on this topic. However, before that, the section will provide some details concerning the specific ways in which STIs are denominated, regulated, and organized around the world and in Colombia so that a better comprehension of the international market behavior and beliefs are stated.

2.1 Sworn Translators and Interpreters around the World

Sworn translators and interpreters are a group of individuals that are also known as legal or court translators/interpreters because of their specific acting scenarios (i.e., mostly legal or govern mental situations; Pym et al., 2012, p. 26). They exist almost all around the world and their ac tivity, denominations, and regulations are very diverse. In terms of activities, what can be seen is that, while their main task in countries such as the United States is to translate/interpret from and into languages like Spanish, Chinese, and Italian (Hammond, 1990), in some South American countries, their task is to translate/ interpret from and into indigenous languages (Quiroz et al., 2015). Concerning regulation, while in Canada their activity is regulated by associations (Hlavac, 2013), in Spain they are regulated by the government (Heras, 2017; Mayoral, 2000; Ordoñez, 2009), and in Colombia, according to Decrees 382 and 2257 (Colombia, Diario Oficial, 1951b; Colombia, Diario Oficial, 1951a), they are overseen by two public universities (Universidad de Antioquia and Universidad Nacional, as reported by Clavijo, 2011). Finally, regarding denominations, while in countries such as the United States and Canada they are called certified, in Europe they are called legal, sworn or authorized translators (Pym et al., 2012), while in some South American countries they are called juramentados (Peru, Brazil), públicos (Venezuela, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay), or oficiales (Colombia, Chile; see Figure 1).

According to Pym et al. (2012, p. 26), all those differences in denominations, specifically certified, sworn, and academically authorized translators/ translations, show, at the same time, a specific way of understanding their actions. Certified is normally a term referring to translations made by a notary accepted or government approved translator who is not necessarily a STIs (see the case of Honduras where there is a specific section in the general secretariat that certifies translations). Sworn, a very old term referring to the moment in which translators literally swore before a notary to be faithful to their work, represents the group of translators who have approved tests administered or ruled by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs or Justice to prove or guarantee their degree of high performance when translating (Stejskal, 2003; see the case of Venezuela or Colombia where exams are the only way to access the profession). Finally, academically authorized is a group of translators who, given their specific training in translation and specifically in legal translation, are accepted by the government to develop these tasks.

2.2 Sworn Translators and Interpreters in Colombia

Sworn translation and interpreting is also a very diverse reality in the Colombian context. Actually, the designation of traductor e intérprete oficial, which is the designation found in laws, could cover three main groups of professionals. The first group is that of translators and inter preters from and to oral languages that are not official in the territory, such as French, Italian, English, among others, who are authorized to perform this activity after approving an exam, according to Decrees 382 and 2257 (Colombia, Diario Oficial, 1951a; Colombia, Diario Oficial, 1951b). In many places around the world, this group is usually known as sworn, so that all ambiguities with other professionals within the field of translation/interpretation can be avoided. The second group are interpreters from and into the Colombian sign language who already have a specific regulation according to Decree 2369 (Colombia, Diario Oficial, 1997) and Resolución 05274 (Colombia, Diario Oficial, 2017) and who, now, must access the profession by means of a certification or a university level training program. In addition, the third group are translators and interpreters from and into native languages that are co official in the Colombian territory who already have a specific regulation in Law 1381 (Colombia, Diario Oficial, 2010). In this last group, the particularity is that they are normally recognized by their communities and the government and not by means of a certification or a training process, as is the case of the first two groups.

STIs, the group in question for the present study, referred as official in Colombia, are regularized by Decrees 382, 722 and 2257 (Colombia, Diario Oficial, 1951b, 1951a, 1982) and Law 962 (Colombia, Diario Oficial, 2005). Nowadays, there are more than 900 STIs registered in the Directory of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs2. These two previous facts contrast with the fact that only one academic course is offered in the country for candidates to become STIs (see Curso de preparación para el examen para traductor e intérprete oficial from Pontificia Universidad Javeriana3) and that there is not any current association, ministry, department or institution to regulate them. In addition, even though there is the norm NTC 5808 from ICONTEC (2010) which defines some translation activities (see ICONTEC, 2010), only one page is dedicated to STIs and its content is still merely informative.

2.3. Directionality

The concept of directionality in languages has always been problematic (T. Pavlović, 2013). In the translation industry and theory, some of the main issues this discussion has risen are the following: (a) denomination (N. Pavlović, 2016), which stands for the ideological, philosophical and practical way of naming languages depending on the use, degree of handling, and control, among others; (b) definition, which relates to some issues in which aspects such as preference or control over some languages when translating or interpreting are tackled (Pokorn, 2005); (c) influence of directionality in the quality of translations, which is a historic issue first problematized by Newmark (1988), but further analyzed by several authors (Beeby, 1998; Campbell, 1998; Gile, 2005; Godjins & Hindaedael, 2005; Kelly et al., 2003; Kiraly, 2000; Marmaridou, 1996); (d) influence of directionality in translators/interpreters training (Dollerup & Loddegaard, 1992; Donovan, 2003; Fernández, 2003; McAlester, 1992; among others); and (e) the relation between directionality and market behavior (Grosman et al., 2000; Lorenzo, 1999, 2002).

For the purposes of this study, only some of the reflections around the concept of directionality will be covered. This study will understand language pairs as follows: “language A” will stand for “Spanish” and “Additional language(s)” will stand for any other language different to Spanish in which a sworn translator or interpreter is certified.

2.4. Key Aspects to Be Taken into Account in a Market Oriented Perspective to Directionality

Market oriented studies in the context of directionality are some of the more productive. In fact, the following are some of the main aspects analyzed in this kind of studies: language status (McAlester, 1992), geopolitical situation of the market in question (Campbell, 1998); mother tongue, native tongue and other ideological and philosophical issues related to de nominations (Kelly et al., 2003), cognitive and linguistic effort, among others. As stated by Gallego (2014, p. 230), when discussing some aspects related to ideological beliefs in directionality, he observes that “la traducción inversa en el mercado profesional existe y puede enmarcarse como una actividad social funcional [reverse translation in the professional market exists and can be framed as a functional social activity].” He also analyzes the fact that reverse or inverse directionality, which means translating from your first language to a second tongue, is actually a very common activity among language service enterprises and professionals, and it has some implications for the practice of translation itself such as the increase of cognitive effort or the lack of quality of the final translation.

By the same token, some other authors such as McAlester (1992) reflect on the fact that this behavior of the market is very often due to the lack of competent translators in minority (in terms of number of speakers) languages such as Finnish, Danish, or some other Scandinavian languages. Both reflections, the one concerning the fact that reverse or inverse directionality is a very active area in many enterprises as well as the one explaining this reality with aspects such as number of speakers or languages status, can also be seen in Colombia. As will be further discussed, Colombia is a very interesting place to describe when it comes to directionality. First, because for years, Colombia has had a very modest economic opening to countries in which Spanish is not the lingua franca. Second, because of the number of native or co official languages co existing with Spanish, that is, more than 65 languages.

As stated by Ferreira et al. (2016):

directionality in translation has recently resulted in an increase in the number of studies that contribute to understanding the cognitive mechanisms that are involved in the translation process (e.g., Alves & Gonçalves 2013; Ferreira 2012, 2014; PACTE 2011; Pavlović & Jensen, 2009). There remain several gaps in what we know about the practice of inverse translation (it) in contrast to direct translation (DT), and as such, additional studies are necessary to make further advancements in TPR. (p. 63)

The aforementioned reflection on the lack of studies carried out on inverse translation (it) has also been emphasized by some other authors. Pavlovic and Jensen (2019) for instance described cognitive and physical aspects in a group of Croatian translators finding interesting patterns in their behavior which indicates a higher effort when doing inverse translating. Ferreira’s studies showed a similar thread when exploring the topic of effort of inverse translating, a topic of interest for the present study. Not only does inverse translating require a higher cognitive and physical effort, it also uprises social issues related to language status and professional status. For this research, these three aspects will be observed and problematized in the segment of sworn translators and interpreters in Colombia.

3. Research Design

The present article is part of a larger project that can be categorized as a sociological case study. The following paragraphs will describe the de tails of this sociological case study, the participants that took part in this project, and the data collection procedures that were carried out.

3.1. Method

Firstly, this study followed a quantitative approach, since its main purpose was to analyze a particular reality by means of the exploration of different variables connected to it, and secondly, because data was analyzed by deductive processes and it aimed at having a linear sequence for the comprehension and analysis of the phenomenon. This study was meant to describe the phenomenon so that an objective comprehension or diagnosis of what is happening in the context of STIs and directionality in Colombia is reached. It is worth mentioning here that further aspects related to some conclusions drawn from qualitative data are also part of the larger project; thus, for the purposes of this article, only the quantitative perspective and results from the study will be presented.

This research study followed a method of sociological case studies. These, as defined by Hancock & Algozzine (2006), focus on “society, social institutions, and social relationships, examining [sic] the structure, development, interaction, and collective behavior of organized groups of individuals” (p. 32), which is the main emphasis of the present study. Accordingly, this article presents some reflections on directionality in the context of the social group of the STIs.

3.2. Participants

The participants of this study are Colombian STIs. According to the Directory of Sworn Translators and Interpreters of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, there are around 900 registries of STIs in the country. According to the same Directory, from those 900 registries, 70 % correspond to STIs certified in English-Spanish, about 7 % to STIs in French Spanish, 7 % to STIs in Italian Spanish, while the rest of the sample correspond to STIs in different languages, such as German, Portuguese, Russian, and others. The present study took the total number of STIs as the universe and subsequently took a representative sample proportional to the size of that universe (Kuznik et al., 2010) of 200 responders for the implementation of a survey. This sampling process was carried out with a confidence level of 94 % and a margin of error of 6 %. The only criterion for the selection of the participants is that they were holders of the certificate of STI delivered by Universidad Nacional, Instituto Electrónico de Idiomas, the Ministry of Justice or Universidad de Antioquia.

3.3. Quantitative Analysis Implemented

All data was organized and described statistically, and then processed and analyzed with some inferential statistical tests assisted by the program RStudio (“RStudio: Integrated development for R”, 2015). It is important to mention that this study took an alpha value (α) or a significance value of 0.06 as reference for all the implemented tests. The main characteristics of the data are:

Quantitative variable: The only quantitative variable examined in this study is denominated here as “percentage of work dedication to translation or interpretation into language A (Spanish).” In order to get this information, translators were asked to indicate the percentage of work they dedicated to translating or interpreting from the additional language of their certification into Spanish. When examining this variable, we applied the Shapiro Wilk test to determine whether this variable had a normal distribution or not; and the result of the test, with a p value of 2.926e 05, led this study to conclude that indeed this variable could only be explored by means of non parametric statistics tests since it does not comply with one of the assumptions parametric tests have to be used: that the quantitative variable(s) must have a normal distribution. As can be observed in Figures 2 and 3, the distribution of this variable is very irregular when comparing it to the Gaussian Curve. To conclude, it is crucial to mention the process of imputation used in this variable. In order to get as much information as possible from the sample, a process of imputation for statistical mean for all the cases in which there was not information about the percentage when crossed with the qualitative variable was made in this study. In almost all cases, a maximum of 11 imputations were made. The statistical mean for this variable was 39.3 %.

Figure 2

Boxplot for the Distribution of the Quantitative Variable: Percentage of Translation/ Interpreting Into Language A (Spanish) From Any Additional Language Among STIs.

Figure 3

Density Plot for the Distribution of the Quantitative Variable: Percentage of Translation/ Interpreting Into Language A (Spanish) From Any Additional Language Among STIs

Qualitative variables: All the qualitative variables were defined by examining the questions proposed for the survey. All of them were organized as follows: (a) demographic aspects (certified pair of languages, decade of certification, place of certification, age, birth place, field of knowledge according to their bachelor’s degree, sex, place of residence, specific training in translation/interpreting); and (b) clientele (time dedicated to projects related to sworn translation/interpretation during a regular week, source of employment, client profile, promotion of services, and interpreters only vs translators and interpreters). During the study, those registries in which no data were available in the qualitative variables were eliminated. This decision was made to guarantee that there would not be any manipulation of the data. In almost all cases, the maximum number of eliminations was 15 out of 200.

Tests made crossing qualitative variable with the quantitative variable: Taking into account that the quantitative variable did not have a normal distribution, all applied tests were non parametric. The following were the main tests applied for the present study:

Mann Whitney U test or Wilcoxon Ranks sums test: This test was applied for the qualitative variables “sex” (man or woman), “place of residence” (Cundinamarca or a place different from Cundinamarca), whether STIs had any specific training in translation or not, whether STIs promoted their work or not, and finally, whether STIs worked as interpreters too or not.

Kruskal-Wallis test: For this test, several hypotheses were made and proven within the same group of sworn translators, all of the remaining variables mentioned before were used here.

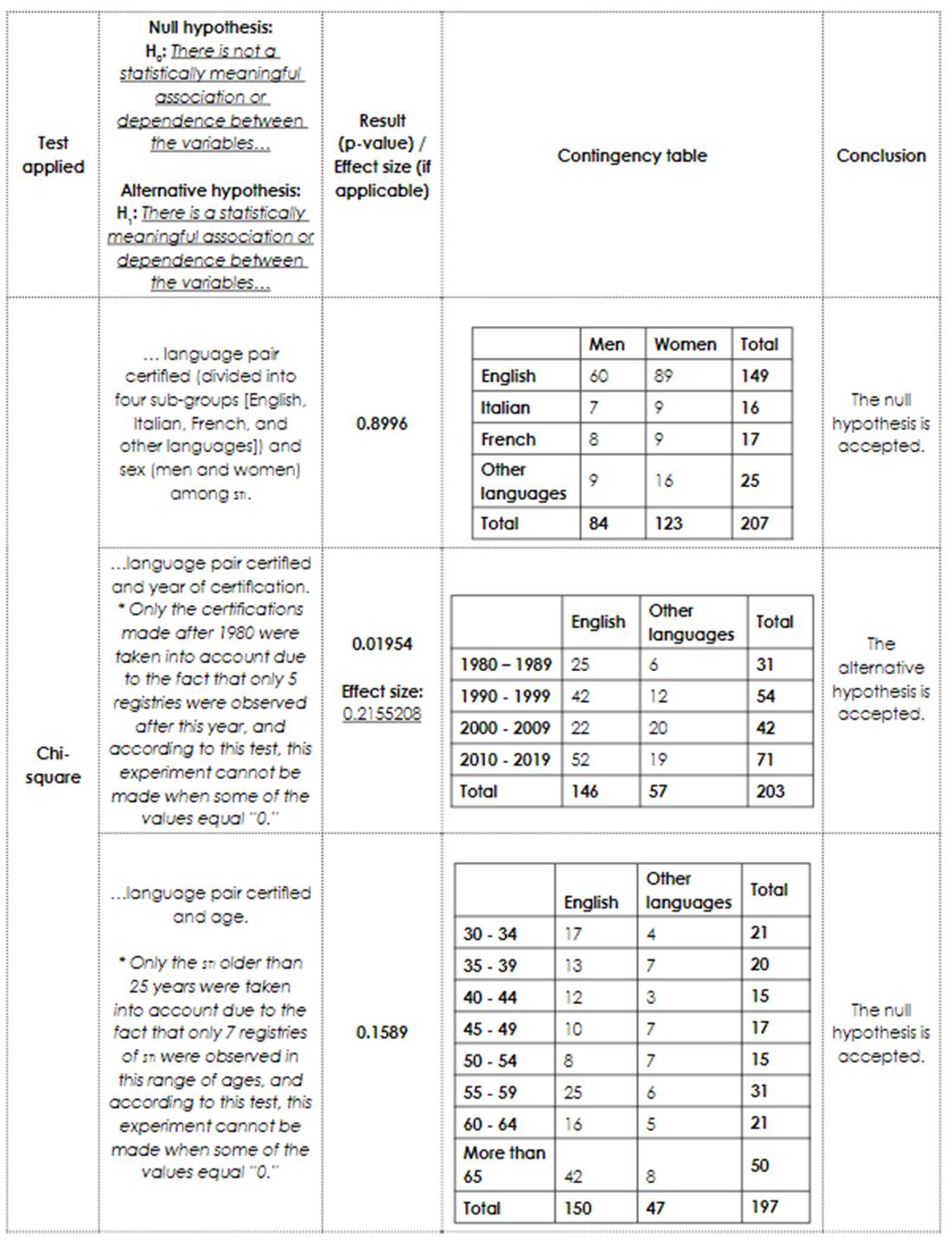

Tests made with qualitative variables: In or der to prove or disprove some hypotheses related to the association or dependence of two qualitative variables that were import ant for this study, the Chi square test was applied. The comparisons were made between the following variables: (a) language pair certified and sex, (b) language pair certified and year of certification, and (c) language pair of certification and age. These comparisons were made to determine if there were any specific behaviors depending on the additional language certified.

4. Results and Discussion

As stated before, there were two main aspects examined by means of statistical inferential techniques for this paper: (a) demographic aspects, and (b) clientele and market related translator profiles. In this segment of the paper, the information will be presented as follows: general descriptive statistical data found in the variables explored for that group of aspects, tables and figures of the variables combined by means of inferential statistical tests, and general comments

¶about the previous two inputs including some references to the existing literature in the field.

4.1. Demographic Aspects

After observing the descriptive analysis of questions related to this issue, some general demographic aspects of the market of sworn translation and interpretation in Colombia are as follows: (a) 60 % of sworn translators and interpreters are women; (b) 70 % of the translators of the sample are located in Cundinamarca, the province where the capital city of Colombia (Bogotá) can be found; (c) 70 % were born in Colombia; (d) half of them -50 %- are over 50 years old; (e) 70 % of them are certified in the language pair English Spanish; (f) 95 % of them are active in translation and interpretation; (g) 90 % of them completed an undergraduate training process; and, (h) 60 % of them completed a graduate training process; (i) even if only 10 % of them are part of an association related to translation or languages, 80 % of them are in favor of creating an association related to sworn translation/interpretation in Colombia; (j) 90 % of them currently interact or have interacted with other sworn translators/interpreters for different purposes.

4.1.1. Inferential Statistical Tests Applied and Their Results

After having looked at the descriptive data, some interesting or appealing aspects called the attention of the researchers. In Tables 1, 2, and 3, readers can observe some of the interesting information that emerged when exploring two variables, the hypothesis made for that specific test and, finally, the results and information extracted from them.

Table 1

Hypothesis, Results, and Conclusions for Tests with Polytomous Qualitative Variables vs. the Quantitative Variable with Kruskal Wallis Tests

Table 2

Hypothesis, Results, and Conclusions for Tests with Dichotomous Qualitative Variables vs. the Quantitative Variable with Mann Whitney U-Tests or Wilcoxon Ranks Sums Tests

On the one hand, as can be seen on Tables 1 and 2, the statistical tests show that there is not a statistically meaningful difference between the median of the percentage of work into Language A (Spanish) and STI certified pair of languages, place of certification, age, birth place, field of knowledge according to their bachelor’s degree, place of residence or specific training in translation/interpreting. This information suggests, at the same time, several issues than can be more deeply discussed or analyzed, given that, as stated before, from a statistically descriptive point of view, the percentage of work into an additional language among STI is superior (60 %) to the amount of work done into Spanish.

The old belief in many places where issues related to translation/interpreting are carried out is that translators should not translate or interpret into an additional language different to their native language (Newmark, 1988). This common belief, strongly enrooted in several organizations, governments, and more evidently, study programs in universities, is questioned in this paper due to the data found and tested for this research study. In Colombia, this is also a very widespread belief (Clavijo et al., 2006, p. 63). The question now is whether university programs should keep focusing their training in translation and interpreting on Spanish. Should we rethink training programs taking into account the fact that inverse translation (into an additional language) is more commonly demanded by the market? Another interesting fact to analyze in this stage is the one related to the special effort translators have to do to inverse translating (Ferreira et al., 2016). This is important since, in Colombia, so far, the topic of directionality and its cognitive implications has not been tackled nor in the general segment of translators nor in the segment of sworn translators and interpreters.

Another interesting aspect related to this finding is that even though there is poor evidence, if any, on the influence of some languages or foreign cultures in the translation market in Colombia, it is important to observe the homogeneity of work dedication among STI regardless of their language of certification. If we take a look at underrepresented languages from the Directory (for instance, Arabic, Norwegian, Swedish, Ukrainian, among others), it will be observed that the translation market behaves the same or, at least, does not behave differently in comparison to other overrepresented languages such as English.

Despite the common belief that places like the capital city, Bogotá, or the touristic capital city, Cartagena, are two of the cities with the biggest amount of work percentage into Spanish, there is not any statistically meaningful difference between the demographic area and the STI interpreting or translation direction.

As can be seen in Table 2, the only test in which the alternative hypothesis was accepted for the demographic category was the one in which the different decades of certification among STI were explored. An interesting aspect of this finding is that this is not a very common topic of discussion in directionality research. Nevertheless, for the Colombian context, it could be said that there is a specific predestination to translate/interpret more into Spanish or into English for STI depending on their decade of certification (Figure 5). When applying the posterior test to determine or to observe the differences, we can observe (see Figure 4) that there are very prominent differences between almost all segments of STI. As will be clarified later, the focus of this research was not to determine why this happens. Instead it aimed to point out that, in fact, some peculiarities in the context of sworn translation and interpretation are taking place and should be described or tackled in the future.

Additionally, another special exploration made with the data that is worth discussing is how languages could behave or associate differently depending on a series of qualitative variables. In Table 3, neither age nor sex are determining or strongly correlated with the language certified by STI. This finding shows once again a certain homogeneity in STI profiles when it comes to language and, at the same time, brings the discussion to the table about the specific external organizational patterns that make sworn translation and interpreting a very similar activity regardless of the language expertise. It is also important to mention the fact that once again the year of certification showed a special association with a variable. In this case, according to the second test in Table 3, there is an association with a size effect of 0.2 between the language certified and the year of certification of STI.

4.2. Clientele and Market Related Aspects

When observing the descriptive analysis, some general clientele related aspects of the market of sworn translation and interpretation in Colombia are the following: (a) 40 % of sworn translators and interpreters use from 1 to 10 hours per week to tasks and projects related to sworn translation/ interpretation; (b) 61 % of the projects and tasks carried out by them are made from language A into the additional language; (c) 60 % of them have as clients natural persons while 30 % of them have private enterprises that are not in the languages services domain as their clients; (d) 60 % of them get their sworn translation/interpretation projects from natural persons; (e) for 50 % of them, the main parameter when defining the budget of a sworn translation is the final number of pages or words of the translated paper; (f) for 50 % of them, the main parameter when defining how to charge clients for interpreting services is the number of hours; (g) for 50 % of them, the main types of documents when translating are legal or juridical documents, followed by commercial documents, and in the third place, academic documents; (h) 60 % of them do not have a well defined technique or strategy to promote their services.

4.2.1. Inferential Statistical Tests applied and Results

After having looked at the descriptive data, some interesting or appealing aspects called the attention of the researchers. In Tables 4 and 5, readers can observe some of the interesting in formation that emerged when exploring two variables, the hypothesis made for that specific test, and finally, the results and information extracted from them.

Table 4

Hypothesis, Results, and Conclusions for Tests with Polytomous Qualitative Variables vs. the Quantitative Variable with Kruskal-Wallis Tests

Table 5

Hypothesis, Results, and Conclusions for Tests with Dichotomous Qualitative Variables vs. the Quantitative Variable with Mann Whitney U tests or Wilcoxon Ranks Sums Tests

As can be seen in Tables 4 and 5, statistical tests show that there is not a statistically meaningful difference between the median of the percentage of work into Language A (Spanish) and the time spent in projects related to sworn translation/interpretation during a regular week. The same is true for the source of employment for STIs or the client profile, and the promotion of services or work as an interpreter. This information suggests, at the same time, several issues than can be more deeply discussed or analyzed, given that, as stated before, from a statistically descriptive point of view, the percentage of work into an additional language among STIs is superior (60 %) to the amount of work done into Spanish.

5. Conclusions

The present article intended to present some re flections and an analysis on the current situation of sworn translators and interpreters in Colombia, as well as some important aspects related to market behavior, with special emphasis on directionality, taken from a larger project in which a sociological case study was implemented. All data and analysis presented here were mainly tackled from a quantitative perspective since the main data source for this part of the project was a survey.

In general terms, it is crucial to take a deep look at the emphasis of training institutions of translators to be in the translation directionality given the previously stated evidence from both descriptive and inferential statistics of the importance of additional languages in the market behavior in the Colombian landscape. It is also essential to rethink the different process of professional updating among translators in Colombia and the lack of training offers for professionals in this area (something already discussed by Gómez, 2019). In reality, as previously analyzed, the fact that inverse translation requires a specific and, in some cases, specialized set of skills should be a topic of discussion in translation studies in Colombia. Authors such as Pavlovic or Ferreira have already problematized the issue of cognitive effort when inverse translating, an understudied topic in Colombia in the general segment of translators and in the segment, as well as among sworn translators and interpreters.

As could be observed before, the current market for STI clients is mostly represented by natural persons. This allows this study to propose a reflection on the informality of the activity, based on the fact that contact with clients, as confirmed by some other research initiatives (Quiroz & Zuluaga, 2014), is made directly by the STI rather than brokered by any agency or institution to back them up in case of any troubles with the project.

As shown by the inferential statistics tests, there is a specific behavior among STI depending on their year of certification. This finding is interesting, but due to the lack of information our survey collected on this topic, we are unable to further develop it. However, this finding allows us to reflect on some differential characteristics among STIs and invites us to determine profiles between translators themselves and observe how their practices vary depending on variables such as year of certification.

It is important to rethink some professional, social, and organizational aspects of translation and interpretation in Colombia and specifically in sworn translation and interpretation. This process of rethinking should focus on aspects such as associations and their influence in daily interactions between STIs and clients, structure and offer of training and updating processes, the need for more cohesive and effective ways to control and surveil the remunerated activity, among others. Some other authors have already reflected on this particularity such as Lupascu (2015).

5.1. Limitations and Future Projects

Although this project collected and analyzed data in an organized and consistent way, it is important to mention a few limitations related to specific parts of the research process.

In terms of the methodological design, this paper focused on presenting and analyzing quantitative data. This focus of interpretation is evidently not enough to be able to read and define from more sociological and perceptional points of view the current state of the profession. Nevertheless, it does offer a diagnosis of the situation and draws some lines or directions to which studies in this area should go. That is why, this paper accepts that all the information given in it should be further inspected from other points of view so that the discussion can be more productive in terms of the reading and understanding of this social group.

In theoretical and practical terms, this paper focused on directionality despite it was not conceived to address this topic. Actually, if readers observe some other studies on this topic, they will find reflections on native languages of the translators/interpreters being part of the sample or life story or linguistic biography of informants, among others. This study acknowledges its focus -when initially structuring the proposal- was not that of directionality, but rather a general overview of sworn translation and interpretation in Colombia. Nevertheless, this study urges some new research and studies to tackle the topic of directionality in a more organized and deeper way, so that the preliminary conclusions or findings drawn can be discussed in a more detailed manner.