INTRODUCTION

Stability is one of the main objectives of orthodontic treatment, with function and aesthetics being compromised in its absence. It is generally believed that dental stability following orthodontic treatment is achieved once the periodontal connective tissues are adapted to the new position. If adaptation fails to occur, teeth tend to partially or completely return to the original position.1

Various procedures, such as fixed retention as proposed by some authors,2,3 seem to be good alternatives to ensure the preservation of the objectives following treatment.4 Among these treatments, interproximal wear, orthodontic overcorrection and circumferential supracrestal fiberotomy (CSF) have been additionally used to prevent relapse in cases of tooth rotations, crowding, and inclined teeth.5-7

One of the reasons for relapse is the existence of supracrestal gingival fibers. When teeth move to a new position, these fibers tend to stretch and reshape slowly. Removing the traction from these elastic fibers prevents a major cause of relapse of previously rotated teeth. By sectioning the supracrestal fibers and allowing them to regenerate while keeping the teeth in the correct position, the relapse by gingival elasticity is significantly reduced.8

CSF is an effective procedure to relieve the stress produced by supracrestal periodontal fibers, which can contribute to the relapse of teeth that have been orthodontically moved. The technique involves inserting a scalpel blade into the gingival sulcus in order to break the epithelial adhesion and supracrestal fibers surrounding the teeth in which a greater retention is sought following orthodontic treatment.9 A recent study evaluated the expression of elastic fiber proteins and type I collagen in the supra-alveolar structure of rotated teeth with orthodontics in rats, in order to check whether circumferential supracrestal fiberomy decreases relapse.10 The study concluded that the collagen fibers of supra-alveolar structures may contribute to relapse in a short time, while elastic fibers may be the reason for rotated teeth to return to their original position after retention.10

The literature has reported the benefits of CSF as an adjuvant in the stability of orthodontic treatment.11,12 However, the stability of orthodontic treatment outcomes with CSF in the short and long term is unknown. In addition, it has been suggested that CSF may cause morphological and structural alterations such as clinical insertion loss, increased probing depth, hypersensitivity, inflammation, and gingival recessions.13,14

Because there is no clarity in CSF’s success after orthodontic treatment, the aim of this systematic review is to assess retention stability following CSF and its effects on periodontal condition compared to retention with no fiberotomy, to demonstrate the effectiveness of CSF as an adjuvant during orthodontic treatment retention at 1+ years of follow-up.

METHODS

Eligibility criteria

This review was conducted through October 2018 and was structured in accordance with PRISMA guidelines, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, and the checklist for reviews. The protocol was registered with the National Institute for Health Research (PROSPERO) with registration number CRD42015023514 for systematic reviews. (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO). The PICO(T/S) format used for systematic reviews was used in this review (Table 1).

Table 1

PICO (T/S) format

Inclusion criteria

This review included all articles that met the following criteria with no language restriction: human studies (including randomized clinical trials, controlled clinical trials, cohorts, cases and controls, case series- with more than 10 patients), evaluating the CSF-related periodontal condition as an adjuvant procedure in the possible stability of orthodontic treatment and assessing the effectiveness of this procedure in the retention phase over a period longer than or equal to 1 year.

Exclusion criteria

The literature search excluded studies in patients who had syndromes or were systemically or periodontally compromised, the use of CSF for purposes other than retention, combination treatments, and patients with additional periodontal treatments.

Search strategy

Detailed search strategies were developed for PubMed and EMBASE (Excerpta Medica Database). The database search was performed using MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), keywords, and Boolean Operators (OR, AND) as follows:

#1 “tooth crowding” OR malocclusion OR “crowding tooth” OR “inadequate tooth alignment” OR recurrence OR relapse OR recrudescence OR “periodontal disease” OR “gingival recession” OR “periodontal pocket”

#2 retention OR retainers OR “orthodontic retainers”

#3 #1 OR #2

#4 fiberotomy OR fibrotomy OR “circumferential supracrestal fiberotomy” OR “gingival fiber surgery”

#5 #3 AND #4

In addition, other sources of information such as gray literature and works cited within the articles found were taken into account.

Values studied

-

1. Reduction of the degree of relapse of dental rotations, measured with:

-

a. Little’s irregularity index: “quantitative measurement of the anterior mandibular alignment”, perfect alignment measured from the mesial part of the lower left canine up to the mesial part of the lower right canine must have an assigned value of 0.15

-

b. Degrees of tooth rotation: changes in the rotation of the upper and lower anterior teeth measured through angles and represented in degrees, taken after the end of treatment and after the retention period.16

-

2. Post-CSF periodontal condition changes measured with:

-

a. Plaque Index: 0: Absence of plaque in gingival area. 1: Plaque film adhered to gingival margin. 2: Moderate accumulation of soft deposits with no periodontal pocket. 3: Abundant white matter in gingival sulcus.13,17

-

b. Gingival Index: 0: Normal gingiva. 1: mild inflammation: slight color change, slight edema, no bleeding on probing. 2: Moderate inflammation: redness, edema and bleeding on probing. 3: Severe inflammation: marked redness and edema, ulceration and tendency to spontaneous bleeding.18

-

c. Depth of gingival sulcus: Measurement taken from the gingival margin to the depth of the sulcus or pocket, measured in 6 areas in each tooth (3 vestibular, 3 lingual).13

-

d. Epithelial adhesion level: Epithelial adhesion is part of the junctional epithelium, which is approximately 2 mm in height and surrounds the tooth neck in the form of a ring.12,19

-

e. Level of adhered gingiva: Measured before and after CSF. Delimited towards the Crown by the free gingival sulcus, at the apical level by the mucogingival limit, where it continues with the alveolar mucosa.12,19

Assessing data validation and extraction

The hypothesis was: is circumferential supracrestal fiberotomy effective as an adjuvant procedure in the stability of orthodontic treatment during retention and what are its effects on the periodontal condition after it has been performed?

Two researchers (L.M.A.G; L.M.R.M.) read and analyzed the documents’ titles, abstracts and full texts independently. Disagreements between these two reviewers were resolved by discussion. When no agreement could be reached, a third reviewer was consulted (A.Z.R.). The following data were extracted and recorded for each article: bibliographic reference, type of study, type of outcome and conclusions.

Bias risk and quality assessment of the included studies

Two tools were used for methodological quality assessment depending on study type. For observational studies, an adapted version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used to assess methodological quality. For Randomized Clinical Trials (RCTs) and Controlled Clinical Trials (CCTs), the Cochrane collaboration tool was used to assess bias risk20 (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2

Checklist to assess the methodological quality of the studies

RESULTS

Search results

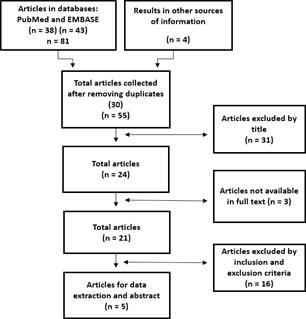

The search strategy identified 81 potentially eligible articles in the databases (EMBASE and PubMed) and 4 articles from other sources of information for a total of 85 articles (Table 4). Of these, 30 were duplicates in the databases, 31 were excluded because of the title and/or abstract, and 3 were not found in full text. Thus, the full text of the 21 selected articles was reviewed, but 16 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria (study type, follow-up period shorter than one year and additional procedures besides fiberotomy) (Figure 1).

Table 4

Databases

Studies included

In total, five articles were selected for review (a randomized clinical trial,7 three non-randomized clinical trials,11-13 one retrospective cohort study,16 Tables 5 and 6). No sample calculation was performed in any of the five studies. A total of 48 subjects were examined in observational studies and 509 subjects in clinical trials.

Table 5

Characteristics of the studies included (observational studies)

| Author | Participants | Methods | Results | Conclusions | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rye (1983)16 | 48 patients, 164 teeth. 91 teeth in control group and 73 teeth in experimental group (CSF). All teeth had retention between 6 months and 2 years. Age: not reported | Retrospective study taken from the UW University Orthodontic Clinic, Seattle (USA) T1: Pretreatment T2: Post-treatment T3: Post retention longer than 2 years. | The average percentage of rotational relapse was significantly different between the control group (39.0%) and the experimental group (22.8%) with a value of p ≤ 0.01 | Fiberotomy reduces the potential for rotational relapse by removing displaced gingival fibers. | There does not seem to be a difference in relapse potential between arches or types of teeth. There does not seem to be a relationship between the degree of rotation and the % of relapse. |

Table 6

Characteristics of the studies included (interventional studies)

| Author | Participants | Methods | Clinical parameters | Results | Conclusions | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hansson C. et al. (1976)13 | 27 patients, 30 rotated teeth, age range from 9 to 22 years. Retention period 8.3 months. Control group (contralateral tooth) and experimental group (Fiberotomy). | Split-mouth study, measuring Silness and Loe’s plaque and gingival index and gingival sulcus depth T1: Pre-surgery. T2: 17 months postsurgery. | Plaque Index: 0 = Absence of plaque in the gingival area 1 = Plaque film adhered to gingival margin and adjacent to tooth area. 2 = Moderate accumulation of soft deposits with no periodontal pocket 3 = Abundant white matter inside the gingival sulcus Gingival Index (Silness and Loe) 0 = Normal gingiva 1 = Mild inflammation 2 = Moderate inflammation 3 = Severe inflammation Depth of the gingival sulcus: Measured from the gingival margin to the bottom of the gingival sulcus at 6 points in each tooth: 3 buccal and 3 lingual. | The plaque index and the gingival index showed no statistically significant differences among treated and untreated teeth with respect to the three measured areas (buccal, lingual and mesial). The average marginal sulcus depth measured in buccal and lingual showed no significant differences among teeth in the same jaw. | No significant differences were found when comparing rotated teeth treated with fiberotomy and teeth without fiberotomy in the same jaw. | The results were obtained by different dentists. Relapse was not evaluated. |

| Edwards, 198812 | 320 patients, 160 of whom were from the control group without fiberotomy, with Hawley plate only, and 160 from the experimental group with fiberotomy and Hawley plate. Age range from 10.9 to 14.1 years. Average age, 12.2 years. | Controlled clinical trial. Little’s irregularity index, epithelial adhesion level and keratinized gingiva band were measured. T1: Orthodontic treatment start. T2: Completion of active treatment and retention initiated. T3: 4-6 years post active treatment. T4: 12 to 14 years post active treatment. | Little’s irregularity index measured as the linear displacement of the anatomical contact points of the maxillary and mandibular incisors. Epithelial adhesion level and keratinized gingiva band, using the North Carolina probe. | In the long term, the control group proved to be less successful in relapsing the anterior segment in both maxilla and mandible. In the control group, the average maxillary relapse at T4 was 49.80%, and 53.55% in the mandible. In the experimental group, the average maxillary relapse at T4 was 20.80% and 34.97% in the mandible. There were no statistically significant differences in epithelial adhesion and keratinized gingiva in either of the two groups at T2. | The relapse measurements at T3 and T4 in the experimental group support the hypothesis that relapse is inherent to supracrestal fibers compared to other factors 4 to 6 years after orthodontic treatment. No clinically significant alteration in epithelial adhesion level was found 6 months after the surgical procedure. The CSF procedure may be more efficient in relieving pure rotation relapse than other types of dental movements. | |

| Tanner et al (2000)11 | 23 patients. Experimental group = 11 patients; control group = 12 patients. Age range: 16.3 years in the experimental group; 15.8 years in the control group | Experimental study (control group with Hawley plate and experimental group with fiberotomy). Crowding was measured with Little’s Irregularity Index. Cephalometries were taken at 4 times: T1: Start active treatment T2: End active treatment T3: 6 months of retention T4: 1 year of retention Periodontal probing was conducted to measure sulcus depth before and after treatment. In addition, gingival recession, periodontal pocket formation, and loss of epithelial adhesion level were evaluated. The longest follow-up time was 1 year. | Little’s irregularity index measured as the linear displacement of the anatomical contact points of the maxillary and mandibular incisors. The parameters of periodontal status assessment were taken before and after the surgical procedure. | There were statistically significant differences in terms of relapse at T4 in both the experimental group and control group. The experimental group had 63.06% average relapse in the mandible and 25% in the maxilla. The experimental group had 1.5% average relapse in the mandible and 1% in the maxilla. There were no significant alterations in the level of epithelial adhesion. The sulcus depth measured with a periodontal probe remained unchanged from T1 to T2 and T3, and the area of adhered gingiva showed no changes in width after the surgical procedure. | In the fiberotomy group there were minimal changes in irregularity index after brackets removal. In the control group there was a significant increase in terms of Little’s irregularity index in both the maxilla and the mandible. Crowding increases regardless of treatment type in patients with and without orthodontic treatment, as a result of the normal aging process. | |

| Wang et al (2003)7 | 81 patients in the control group and 48 patients in the experimental group. Age range: 11.5 to 15 years. Average 13.07 years. | Randomized clinical trial. The control group had 81 patients with Hawley plate. The experimental group was divided into two groups: 23 patients with fiberotomy + stripping + Hawley plate and 25 patients with fiberotomy + Hawley plate. 3 times were taken: T1= Pretreatment T2 = At the end of orthodontic treatment T3 = Retention phase | Little’s irregularity and intercanine width were evaluated. | Irregularity increased across all groups at T2 and T3, being significantly greater in the control group between T2 and T3. (p < 0.05). The average relapse rate of the control group was higher compared to the experimental group. The average relapse rate in the experimental group reduced by a 21.61% compared to the control group (14,23% in the maxilla and 28.99% in the mandible). Periodontal tissue is not compromised when performing the fiberotomy procedure. | Modified supracrestal fiberotomy may be effective in relieving relapse of crowding and rotations of anterior teeth. Combined fiberotomy and stripping treatment can help maintain post-retention stability of anterior mandible teeth. | For results analysis purposes, only the experimental group with fiberotomy was taken in order to eliminate potential confusion biases. |

Methodological quality of the included studies, evaluation of orthodontic treatment relapse and periodontal condition

Evaluation of studies

The evaluation of the methodological quality of all selected studies was carried out with the modified NOS scale. Four studies showed average methodological quality (one study with 10 points,12 one with 9 points,7 and two with 8 points11,13) and one study had low quality (3 points16). Only one study had blinding.12 The follow-up period was appropriate in four studies7,11,13,16 (Table 7).

Tabla 7

Evaluation of the studies’ methodological quality

| Variable | Tanner et al, 200011 | Edwards, 198812 | Hansson C. et al, 197613 | Rye, 198316 | Wang et al, 20037 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection | 1. Sample size calculation | |||||

| 2.Representativeness of experimental group | ||||||

| 3. Selection of control groups | * | * | * | |||

| 4. Assessment of orthodontic conditions | * | * | * | |||

| 5. Clear description of surgical procedure | * | * | * | * | ||

| 6.Training/calibration of evaluators | * | * | * | |||

| 7. Prospective data collection and description of selection criteria | * | * | * | |||

| Comparability | 1. Group comparability (patients) | * | * | * | * | |

| 2. Management of confusion factors | ||||||

| Results | 1. Evaluation of orthodontic results | * | ||||

| 2. Criteria applied to assess orthodontic conditions | * | * | * | * | ||

| 3. Adequate follow-up of patients | * | * | * | |||

| Statistics | 1. Relevance/validity of statistical analysis | * | * | * | * | * |

| 2. Unit of analysis (response rate) recorded in the statistical model | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Total | 8 | 10 | 8 | 3 | 9 | |

Evaluation of orthodontic treatment relapse and periodontal condition

Three studies reported an appropriate method for evaluating orthodontic treatment relapse using Little’s irregularity index7,11,12 and one study used rotation evaluation by degrees.16

The periodontal condition described by Hansson13 reported an adequate measurement method. Two studies used a periodontal probe.11,12 One study was not clear on the method used7 and another study did not report results in this regard.16

Orthodontic treatment relapse after performing CSF in the short and long term

Rye (1983)16 used degrees of rotation of each tooth to evaluate post-orthodontic relapse. The control group showed an average rotational relapse of -7.1 degrees (range: -19.9 -5.7 degrees), while the experimental group had an average relapse of -4.6 degrees (range: -18.3 -9.1 degrees). The difference in rotational relapse averages was statistically significant between the control and experimental groups (p < 0.01). The relapse rate in the control group was 39.0%, and 22.8% in the experimental group.16

Edwards (1988) conducted a follow-up clinical study for 15 years, reporting that the control group had greater relapse in the anterior segment of both maxilla and mandible in the long term. The average maxillary relapse at T4 was 49.80%, and 53.55% in the mandible. In the experimental group, CSF showed greater success in controlling relapse of the anterior segment in the maxilla and mandible, with an average of 20.80% and 34.97% respectively.12

Tanner et al (2000) observed increases per follow-up year in terms of average relapse of 25% in the maxilla and 63.6% in the mandible in the control group. In the experimental group there was an average relapse of 1% in the maxilla and 1.5% in the mandible.11 In a 2.4 years post-CSF follow up, Wang et al (2003) reported that irregularity increased in all groups at T2 and T3 and that it was significantly greater in the control group between T2 and T3 (p <0.05)7. In the experimental group, the average relapse decreased by 21.61% compared to the control group.

Periodontal conditions after performing CSF in the short and long term

In their study, Hansson et al (1976) showed the average plaque index in CSF-treated teeth at the mesial (x̅ = 0.77), buccal (x̅̅ = 0.55) and lingual levels (x̅ = 0.93), compared to those not treated in mesial (x̅ = 0.97), buccal (x̅ = 0.60) and lingual (x̅ = 0.93), as well as the average gingival index between CSF-treated teeth at the mesial (x̅ = 0.97), buccal (x̅ = 0.77) and lingual levels (x̅ = 0.97) and those not treated in mesial (x̅ = 1.03), buccal (x̅ = 0.70) and lingual (x̅ = 0.83). No statistically significant differences were found in relation to the three recorded measurements and the two indices obtained. No significant differences were identified between teeth evaluated in the same jaw in relation to average depth of the gingival sulcus measured at the buccal (treated x̅ = 1.70 vs. untreated x̅ = 1.77), mesiobuccal (treated x̅ = 2.27 vs. untreated x̅ = 2.20) and distobuccal (treated x̅ = 2.13 vs. untreated x̅ = 2.23).13 Edwards (1988) compared the level of epithelial adhesion (treated x̅ = 0.0 vs untreated teeth x̅ = 0.0) and keratinized gingiva loss (treated 0.0 vs. untreated teeth x̅ = 0.0) None of the two groups showed statistically significant differences at 1 and 6 months.12 Tanner et al (2000) observed no significant alterations in the level of epithelial adhesion. Sulcus depth remained unchanged from T1 to T2 and T3, and the width of adhered gingiva showed no change after the surgical procedure.11 Similarly, Wang et al (2003) found no periodontal tissue compromise when performing CSF.7 Rye (1983)16 was the only study showing no results concerning the periodontal condition following CSF.16

DISCUSSION

Summary of key results

The results from other studies are consistent with the results of the studies evaluated for this review,7,11-13,16,21-23 which show that CSF-plus an adequate retention period-is a successful approach in reducing short-term and long-term orthodontic recurrence (moderately recommended, based on level-B evidence-multiple studies of moderate quality).7,11-13,16,24

Quality of studies, limitations and possible biases in the review process

Except for the study reported by Rye in 1983,16 the studies by Edwards in 1988,12 Tanner et al 200011 and Wang et al in 20037 used Little’s irregularity index to assess the degree of relapse. This method-commonly used in the literature-was described by Little as an index taking a horizontal line as a reference to measure the displacement of the anatomical points of contact of each lower incisor, that is, the sum of the five displacements represents the relative degree of anterior irregularity.15

Regarding the stability of periodontal tissues following fiberotomy, the studies evaluated different clinical parameters. Hansson et al, in 1976,13 described the plaque index, gingival index and gingival sulcus depth. Edwards in 198812 and Tanner et al in 200011 evaluated changes in the position of epithelial adhesion, gingival sulcus depth, and changes in keratinized gingiva width. However, Tanner et al do not show statistical results related to the reported clinical findings.

The heterogeneity of the clinical parameters evaluated and the measuring instruments used results in a big methodological problem for the interpretation of results, taking into account the variability of the clinical criteria used to determine periodontal condition. This particularity allowed us to generate only qualitative general analyses on the impact of CSF on periodontal tissues.

Another limitation has to do with the methodological quality of the included studies. 80% of the studies had a moderate bias risk and only one article had a high bias risk (20%). The evidence supporting the clinical applicability of CFS in orthodontic stability is poor, although it suggests that this procedure could be effective in controlling short and long-term post-orthodontic relapse. Additional studies are needed to provide stronger available evidence in the future.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies

Similar previous studies, such as that of Ahrens et al in 1981,23 suggest that surgery to remove the influence of supracrestal fibers on orthodontic treatment relapse is an effective method for achieving short-term stability, with statistically significant results as a lower degree of relapse is observed when compared with a control group, although it is important to mention that this study has a variation in terms of the surgical technique performed, as well as very short follow-up time (30 days). The same author reports that there was no alteration at the periodontal level following the procedure.

The study by Rinaldi in 197925 evaluated the periodontal condition 4 months after CSF, finding out that gingival sulcus depth was maintained without any alteration. The author also reports the apical migration of epithelial adhesion in the lingual area of anterior teeth in both the maxilla and the mandible. However, this clinical finding was minimal, without any adverse consequences on periodontal tissue. It concludes then that the surgical technique carried out according to Edwards is a benefit in young patients, helping to maintain the stability of treatment and periodontium.12

Other studies found in this search but not included in the systematic review because of failure to meet the inclusion criteria show that CSF is a procedure that does not cause periodontal alterations while decreasing orthodontic relapse,5,22 agreeing with the results of the five articles used in this review.

Protocol for performing fiberotomy

The periodontal fibers that influence stability are periodontal ligament fibers and supra-alveolar fibers; the former are completely remodeled only after 2 to 3 months and the latter are stable and have a slower rotation. In the CSF technique, transseptal fibers are cut interdentally into the space of the periodontal ligament, healing between 7 and 10 days. The study by Shekar et al in 201726 concluded that fiberotomy is not indicated during the active movement of teeth or in the presence of gingival inflammation. When performed on healthy tissues after orthodontics, there is minimal insertion loss.

There is no specific protocol on the ideal method and time to perform fiberotomy. Reitan27 reported that the largest relapse occurs within 5 hours of orthodontic elimination. Therefore, Proffit28 suggests that this procedure should be performed at the end of treatment, a few weeks before removing the orthodontic devices. Similarly, Taner et al,11 Rye 16 and Wang et al7 report the completion of surgery before brackets removal. On the other hand, Edwards indicates the procedure at the time of brackets removal.12

Other treatment modalities to ensure orthodontic treatment stability

Although studies evaluating other procedures in addition to fiberotomy were excluded as potential confounding factors, some authors6,7 describe re-approximation as a way to improve the results obtained with fiberotomy and thus ensuring the long-term stability of orthodontic treatment.

According to these authors, re-approximation performed in a precise and conservative manner increases the long-term stability of the anterior mandibular segment. However, the combination of fiberotomy plus re-approximation cannot be considered as the permanent solution for all problems associated with treatment.6

Using laser or electrosurgery

The use of fiberotomy to decrease relapse following orthodontic treatment has shown to be highly effective in several studies; however, although this can be considered a non-invasive technique, there are some associated morbidities such as bleeding, pain and/or discomfort on the patient.29 Alternative methods have therefore been described to improve these conditions, such as the use of electrosurgery and laser.29-33

Using laser to perform fiberotomy shows numerous benefits over the conventional technique, since it is considered that with this technology patients experience minimum pain and inflammation, little or no bleeding and a low probability of postoperative infection, as the laser sterilizes the irradiated area of the region to be treated.28

The Erbium laser is the most recommended for fiberotomy (Er: YAG or ER, Cr: YSGG) because it allows fiber ligaments to re-establish a tissue pattern without inducing superficial necrosis. The diode laser is another alternative for this procedure; however, it can cause the tissue to detach, thus slowing healing.34 So far, only animal studies using diode lasers for fiberotomy have been found during the retention period after orthodontic treatment.30 It should be noted that this type of laser is the most widely used in clinical trials to evaluate the effectiveness of fiberotomy, taking into account that it is little absorbed by teeth and bones, making it a safer procedure due to the lower risk of hard tissue damage.35

In 2017, Faramarz et al used the Nd:YAG laser for CSF. Their results showed that the location of gingival margin and alveolar bone crest remained unchanged after fiberotomy with the Nd:YAG laser during the orthodontic forced eruption procedure. It was also concluded that it can be used as a suitable method for fiberotomy as it produces little pain and allows good manipulation, allowing it to be used to the depth of the sulcus. Similarly, it shows low absorption in water and hard dental structures, but a high absorption in pigmented tissues such as hemoglobin, which makes it efficient in the hemostatic ablation of soft parts. This laser decreases fibroblasts and adhesion of periodontal fibers to the root surface during the healing process. Although this is known to be a disadvantage for routine periodontal treatment, it does benefit fiberotomy with fibers not adhering to dental surfaces.36

CONCLUSION

The studies included in this systematic review suggest that fiberotomy is an effective method to prevent relapse of previously rotated teeth and that it does not cause periodontal alterations in terms of insertion level and sulcus depth. Additional studies with high methodological quality are suggested in order to add enough evidence with a positive recommendation for CSF to be included as a therapeutic procedure within clinical orthodontic retention protocols.