INTRODUCTION

Dental fluorosis is the hypomineralization of tooth enamel as a result of fluoride intake for a prolonged period during enamel formation.1 It is characterized by lesions ranging from white spots with a mottled patches appearance to confluent pitting. This fluorotic enamel has increased porosity, leaving the surface exposed to other conditions, such as tooth decay, extrinsic staining, sensitivity, and malocclusions.2 The severity of this oral pathology depends on the amount or concentration of ingested fluoride, the duration of exposure, the level of tooth development, the age at which the individual is exposed to excessive amounts of fluoride, and individual variation or susceptibility.3 Dental fluorosis, as a situation that must be unavoidably notified, is of interest to public health and local administrations, hence the importance of knowing the severity and risk factors associated with this disease, as well as monitoring and controlling the proposed actions for the improvement of oral health. All cases in patients aged 6, 12, 15 and 18 years with clinically confirmed fluoride exposure must be entered to the National Public Health Surveillance System (SIVIGILA).4

In recent decades, there has been an increase in the prevalence of dental fluorosis worldwide, with percentages ranging from 7,7 to 80,7% in areas where fluoridated water is available, and from 2,9 to 42% in areas without fluoridated water.5 In Colombia, the 1998 Third National Oral Health Survey (Estudio Nacional de Salud Bucal, ENSAB III)6 identified a fluorosis prevalence of 11.5% in the evaluated population; ENSAB IV7 found a Community Fluorosis Index (Dean’s CFI) of 0.13 at age 5; 0.9 at age 12 and 0.84 at age 15. The CFI considers that a country has a public health problem in fluorosis when this index exceeds the 0.6 value.

In 1998 and 2004, Colombia’s Ministry of Health called together local and foreign experts to analyze the situation in the country regarding cavities and the public health decision to supply fluoride in salt and other sources. This analysis recommends maintaining the use of mass fluoridation, given the high prevalence of tooth decay, and strengthening the measures of epidemiological surveillance and Inspection, Surveillance and Control (Inspección, Vigilancia y Control, IVC).8

The purpose of IVC of fluoride exposure (sentinel) is to produce useful, reliable, timely and continuous information on dental fluorosis, its risk factors and protective factors in sentinel units nationwide, in order to adjust the current policies on fluoride supply, contributing to the prevention of cavities and the control of dental fluorosis.9 As for previous research, a number of studies have been conducted, including the one carried out in the municipality of Frontino, which concludes that there is sufficient scientific evidence on the positive effects of fluorides on the prevention and control of tooth decay, pointing out the importance of recognizing the potential harmful effect of continued and excessive intake of fluoride, specifically during the tooth formation stage.10

In consequence, the present study seeks to determine the factors associated with dental fluorosis in children and teenagers from the city of Montería, Colombia, through Dean’s CFI analysis,11 conducted by dental service providers on the form established for this mandatory report.

METHODS

This was a descriptive, quantitative, retrospective study. Due to the study population size and the availability of a database in this study, the statistical analysis was carried out using all cases. The sample was then made up of dental fluorosis cases in schoolchildren aged 6, 12, 15 and 18 years (136 cases), reported to the Surveillance and Control System (SIVIGILA) from January to December 2016 in Montería, Córdoba. Validity in the processing of the “fluoride exposure” report sheet (INS code 228)12 is given by the competence of oral health practitioners, as they are periodically provided with technical assistance by the Municipal Board of Health, including training on how to fill out the sheet.

The report sheet was taken as the primary source, considering the following categories and definition for data collection:

The SIVIGILA information was processed according to the objectives and variables of the report sheet by developing a database, which was used to calculate absolute and relative frequencies, as well as average years plus standard deviation and means (total and by sex). The Cronbach Alpha coefficient was used to assess the measurement scale reliability and as a weighted mean of the correlations among variables. Finally, the frequency of fluorosis was calculated in schoolchildren aged 6, 12, 15 and 18 years, both globally and by severity degrees based on data observed on the report sheet.

In addition, the multivariate technique known as multi-correspondence analysis was used, seeking to represent the proximity in a set of objects or subjects in a small geometric space, in order to transform the similarities among cases into distances suitable for representation in a multidimensional space.

Windows’ Excel and SPSS Statistics 24 were used for statistical processing and data analysis. The data were finally presented in tables and charts to perform the final analysis and discussion.

As for ethical aspects, according to Article 11 of Resolution 8430 of 1993, this was classified as a no-risk study, as it used retrospective documental research techniques and methods, with no intentional intervention or modification of the participants’ biological, physiological, psychological, or social variables.

In addition, the study reviewed anonymous records and addressed sensitive aspects of human behavior. It also considered the methodological principles to safeguard the interest of science while respecting people’s rights.

The databases with information from the report sheets did not contain the participants’ identifying information, so the right to privacy was not violated; no person was intervened in the procedures performed; therefore, there was no violation of bioethical principles.

This study had an informed consent from the Municipal Board of Health, by an Universidad de Córdoba’s written request to carry out the research project; it also obtained approval of the Ethics Committee of the School of Health Sciences.

RESULTS

In terms of the sociodemographic factors of the study population, there were 81.6% of cases of fluoride exposure in the subsidized system, with 89% of patients living in the city center. This is consistent with information from Bulletin 16 of the National Health Institute (Instituto Nacional de Salud, INS)13 (Table 1).

Table 1

Sociodemographic factors

Concerning risk factors, the followingresults were obtained: toothpaste intake: 28.7%, topical application of fluoride in the last year: 17.6%, mouthwash intake: 6.6%. In addition, breastfeeding was included as a variable, as it appears in the report sheet as a protective factor; however, its absence becomes a risk factor for dental fluorosis. This study showed that 49.3% of patients were breastfed, which according to the American Dental Association (ADA) ensures children’s oral care.14 Risk factors and protective factors are shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Risk factors and protective factors associated with dental fluorosis

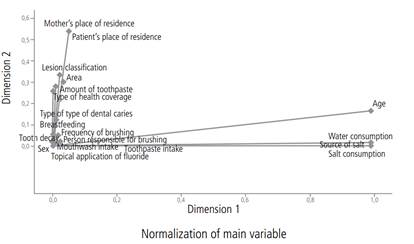

To explain the case under study, the variables were reduced to only two dimensions in order to show a summary of the model, where inertia indicates the proportion of data variance explained by each dimension, showing 46% data variability: 31% in the first dimension and 15% in the second.

In addition, the researchers explored the possibility of dividing total inertia into components suitable to be connected to each dimension, so that the inertia shown by a given dimension can be evaluated by comparing it to total inertia. For example, the first dimension shows 68% (0.309/0.456) total inertia, while the second dimension shows 32% (0.147/0.456).

Also, the Cronbach Alpha coefficient was used to estimate the reliability of the measurement scale; in this model, an average value of 0.94 was obtained, providing greater reliability for the analysis, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3

Model summary

| Cronbach’s Alpha Dimension | Variance calculated for total (eigenvalue) and inertia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.962 | 18.514 | 0.309 | |

| 2 | 0.902 | 8.817 | 0.147 | |

| Total | 27.331 | 0.456 | ||

| Average 0.943a | 13.665 | 0.228 | ||

Table 4

Discriminatory measurements

Below are the discriminatory measurement values for each variable in each dimension, which are equivalent to the variance of the quantified variables, where the máximum value equals the unit, which is achieved if all subjects’ scores fall into mutually exclusive groups, and in turn the scores are identical within each group.

Table 4 shows (in boldface) the variables most related to dimension 1.

The highlighted variables show a group away from the other variables, indicating that there is some pattern for the relationship among them. As for patient’s and mother’s place of residence, both are significantly related to dimension 2, as are lesion classification, area, amount of toothpaste, and type of health coverage, but considering that the latter have low scores.

All the other variables with very low scores fall in both dimensions, as shown in Figure 1.

The analysis by Dean’s CFI shows that most patients have a moderate lesion with 52.2%, followed by mild lesion with 45.6%, very mild with 16.2%, severe with 2.2% and questionable with 1.5%. In addition, the percentage of cases reported as moderate was 52.2%, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6

Classification of lesions in fluorosis patients from the city of Montería

| Lesion classification | Patients | Percentage | Cumulative percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Questionable | 2 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Very mild | 20 | 14.7 | 16.2 |

| Mild | 40 | 29.4 | 45.6 |

| Moderate | 71 | 52.2 | 97.8 |

| Severe | 3 | 2.2 | 100.0 |

| Total | 136 | 100.0 |

Here is the description of the variables of a patient selected from the total sample: a patient with a mild lesion is a male, aged 18 years, covered by the contributory system; he lives in the town center, brushes 4 times a day and uses toothpaste on 3/4 of the brush head.

Patients with very mild lesions are females aged 12 years, living in the town center; they brush twice a day and use toothpaste they brush twice a day and use toothpaste on 2/4 of the brush head.

Patients with moderate lesions live in urban areas, are aged 15 years, are covered by the subsidized system, brush one to three times a day and use 4/4 toothpaste. Patients with severe lesions live in the urban area and are covered by the subsidized system, are aged 15 years, have non-cavitational decay, use 1/4 of toothpaste and brush once a day.

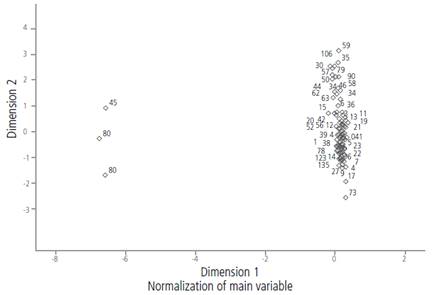

In addition, individuals 45, 80 and 85 are isolated from the rest of the group. These are 6-year-old patients who were evaluated for the source of water consumption, salt source, and salt type, as shown in the report sheet.

Finally, questionable lesions in patients are not associated with any of the categories of variables considered in this study, as shown in Figure 2.

DISCUSSION

In terms of sociodemographic factors, dental fluorosis affects children and teenagers from the city of Montería aged 12 to 15 years mainly, with a lower proportion in children aged 6 years. In addition, 61.8% of cases occurred in females. These results are similar to those in studies conducted in Cartagena15 and Mexico.16

As for other sociodemographic data, 89% of all fluorosis patients live in the city center and 81.4% are covered by the subsidized system. These figures are similar to those reported nationwide in Bulletin 16 of the National Health Institute,17 which reports 87.3% of dental fluorosis in the subsidized system, 66.3% from the city center and 28% of cases reported in six-year-old kids.

The proportion of dental caries in this study was 75%, with cavitations in 47%, which is consistent with reports by the World Health Organization (WHO)18 and Colombia’s Ministry of Health and Social Protection,19 which state that dental caries is the most prevalent dental disease, with very high levels in national surveys. This also agrees with reports by the sentinel surveillance system concerning fluoride exposure, which has been led by the National Health Institute (Instituto Nacional de Salud, INS) since 2012,20 finding out that by the first half of 2016 more than 50% of people with dental fluorosis had cavities.

Concerning the amount and intake of toothpaste, 51.5% of all fluorosis patients brush with 3/4 toothpaste depending on the size of the brush head, and 23.5% use 4/4. These results indicate that toothpaste is used in more than half the brush, which can increase fluoride intake; however, 71.3% of patients said they did not swallow toothpaste.

This is a hard to control factor because of its unintentional nature, but it could affect fluoride absorption because young kids find it difficult to expectorate toothpaste remains during brushing. This has been demonstrated by some studies confirming the intake of toothpaste by 30 to 40% before the age of 6.21

As for brushing frequency, 48.5% of patients say they brush three times a day, followed by twice a day by 40.4%. It is important to note that brushing frequency and the use of fluoride toothpaste are oral hygiene habits, which can positively or negatively affect oral health conditions; in this case, the results are satisfactory in relation to the established frequency.

Finally, in identifying dietary salt consumption as a risk factor highly associated with the presence of dental fluorosis, the frequent use of this mineral in Colombia’s Caribbean region should be noted, as high consumption levels can favor the onset of fluorosis.

For the classification of dental fluorosis lesions, Dean’s CFI diagnostic criteria were used, showing that most cases are moderate, in agreement with the results reported by Ramírez et al.22 Hence the importance of a timely intervention of the population at risk, in order to avoid the increase of this pathology, which has become a public health issue with international implications as reported by Agudelo-Suárez et al.23

In other respects, to control the risk factors associated with oral pathologies, it is important to empower patients and their families, providing them with the information needed for self-care. In relation to oral health practices, the ENSAB survey agrees that a high percentage of the population has internalized the role of brushing in the prevention of diseases like caries and gingivitis, which is clearly a result of the increased number of messages, educational and advertising campaigns in recent years, since causal factors and the way to combat them are frequently mentioned, improving the existing knowledge in this sense.6,7

However, the findings suggest that a portion of the population has not been impacted yet, and that induced demand, early detection, and specific protection should be encouraged in order to reduce the prevalence of fluorosis and other oral pathologies. In addition, the publication of this type of studies helps improve preventive strategies by competent local bodies, in order to control risk factors associated to oral health.

Regarding fluoride application, this remains a dental practice used as a preventive measure to avoid the onset of carious processes; however, as a result of dental fluorosis, dental practitioners are making a rational use of fluoride, as confirmed by Martignon et al.2

On the other hand, oral health personnel should be aware of the importance of proper clinical examination and transparency in processing the report sheet to notify SIVIGILA, in order to provide quality and reliable information.

As a recommendation for further studies, it is suggested to perform a correlational analysis to establish the condition of drinking water, as this study did not evaluate the presence of fluoride in food, drinks, cooking salt, toothpastes, urine samples, and other substances that could explain the condition of fluorosis.

To improve the public policy in oral health, it is necessary to design education plans and to develop strategies to address dental fluorosis risks within the Health Situation Analysis (Análisis de Situación de Salud, ASIS). It is also necessary to support the processes of salt and water quality monitoring, including the management of natural water sources and aqueducts in rural areas.

Local health divisions should further analyze the situations that affect population groups, with the support of technical capacity, human resources, and public health laboratories to conduct studies on fluoride (and iodine) concentrations in salt, water, and other carriers, including toothpastes.

In addition, it is critical to recognize the role of continuing education campaigns, which must be permanent and target the effects of fluorides in the body, seeking a better parental supervision of children’s brushing, especially in the case of kids in school age and at increased risk of dental fluorosis.

As for health service providers, they should periodically monitor the processes and run induction and re-induction plans to train practitioners in the detection and management of this pathology.

Within the limitations for comparing data on sex and cavities, it should be noted that some studies fail to differentiate the average age groups, while other studies divide age groups differentiating children and adults.

Finally, universities are encouraged to promote research on the stability of fluoride in salt, milk and water among undergraduate and graduate students, since the stability of each compound may vary once in the consumer’s hands. In addition, it is necessary to conduct cost-effective analysis of fluoride supply mechanisms due to the prevalence of tooth decay and dental fluorosis.

CONCLUSIONS

This study and its findings demonstrate the relationship of dental fluorosis to risk factors in the vulnerable population, which could be influenced by the unintentional intake of fluorides present in dietary salt or toothpaste due to the amounts used and the frequency of brushing-factors that can be intervened through education and awareness-raising by dental practitioners, empowering patients and caregivers while promoting self-care.

For the most part, the lesions in this study were classified as moderate; therefore, immediate action is needed to prevent the loss of tooth structure and the progression of the oral pathology.

Being an event of public health interest, oral health professionals must be trained and have sufficient knowledge for a timely diagnosis of dental fluorosis, being aware of the diagnoses, protocols, and treatment to provide patients with timely care.