José Luis Castro Montero**

DOI: 10.17533/udea.esde.v74n164a04

*

Artículo de investigación. Es el resultado del proyecto El reemplazo

constitucional en América del Sur: acercamiento empírico.

Grupo de Metodología del Derecho de la Universidad de Tilburg. Fecha de

terminación de la investigación: 12/12/2016.

** Abogado y docente de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Ecuador, Estudios en Derecho Constitucional en la Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar. LLM de la Universidad de Tilburg (Países Bajos) y la Universidad de Leuven (Bélgica). Correo electrónico: [email protected] ORCID:0000-0003-2997-1428

Almost all constitutions have a beginning and an end; enactment supposes its birth, while replacement entails its death. Like all living beings, written constitutions can pass away because of many causes. Among other factors, political, economic and social conditions, but also constitutional design features are called to be the leading causes of what is hereby denoted as constitutional replacement. Why do some written constitutions survive longer than others? To what extent are political, economic, and legal factors, the determinants of constitutional replacement? To answer these questions, this article presents an empirical study of risk and protective factors of constitutional mortality, among five South American countries, namely Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela, in the period 1946 - 2016. This time period is especially interesting due to its variability. Previous literature insights are confirmed insofar evidence suggests that bicameralism tends to live longer, despite adverse political and economic conditions.

Keywords: constitution; constitutional amendment; democracy; constitutional durability; constitutional mortality; South America.

Todas las constituciones tienen un inicio y un final. Nacen cuando son promulgadas y su reemplazo conlleva su muerte. Como todos los seres vivientes, las constituciones pueden morir debido a diversos factores. Entre los más importantes están los factores políticos, económicos, sociales y características sobre el diseño constitucional como las variables explicativas del reemplazo de las constituciones. ¿Por qué algunas constituciones sobreviven más tiempo que otras? ¿En qué medida diversos factores políticos, económicos, sociales y de diseño constitucional influyen en la reforma total de las constituciones? Para responder estas preguntas, este estudio presenta el análisis empírico de una base de datos original sobre los factores de prevención y riesgo de las constituciones promulgadas en Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Perú y Venezuela, entre 1946 y 2016. Este periodo resulta interesante debido a su variabilidad institucional. Los principales hallazgos del presente estudio refieren que aquellas constituciones que instituyen mecanismos de difusión de poder político, como asambleas bicamerales, perduran inclusive ante condiciones sociales y económicas desfavorables.

Palabras clave: constitución; reforma constitucional; democracia; durabilidad constitucional; mortalidad constitucional; América del Sur.

Toda constituição política tem um início e um final. Nascem quando são promulgadas e a sua substituição acarreta a sua morte. Como todos os seres vivos, as constituições podem morrer devido a diversos fatores. Dentre os mais importantes, alguns trabalhos prévios analisam fatores políticos, econômicos, sociais e características sobre a forma constitucional como as variáveis explicativas da substituição das constituições. Por que algumas constituições sobrevivem mais do que outras? Em que medida diversos fatores políticos, econômicos, sociais e de forma constitucional influem na reforma total das constituições? Para responder estas perguntas, este estudo apresenta a análise empírica de uma base de dados original sobre os fatores de prevenção e risco das constituições promulgadas na Bolívia, Colômbia, Equador, Peru e Venezuela, entre 1946 e 2016. Este período resulta interessante devido a sua variabilidade institucional. As principais descobertas deste estudo indicam que aquelas constituições que instituem mecanismos de difusão de poder político, como assembleias bicamerais, perduram inclusive diante de condições sociais e econômicas desfavoráveis.

Palavras-chave: constituição; reforma constitucional; democracia; durabilidade constitucional; mortalidade constitucional; América do Sul.

Why do some written constitutions survive longer than others? Almost all constitutions have a beginning and an end; enactment supposes its birth, while replacement entails its death. Like all living beings, written constitutions can die from many causes. Among other factors, political and economic conditions, but also constitutional design features are called to be the leading causes of constitutional replacement. In this paper, an empirical comparative analysis of risk and protective factors of constitutional replacement, among five South American countries, namely Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela, between 1946 and 2016, is presented. The main findings suggest that institutions such as bicameralism tend to lengthen the lifespan of constitutions. This might be due to the higher number of veto players and level of consent required for passing any constitutional replacement initiative in a bicameral legislature. The preventive effect of bicameralism even holds when taking political and economic conditions into account.

This contribution focuses on five Andean states that evince a somehow similar trend when considering constitutional replacement practices (Elkins et al., 2009). Other comparative equivalencies are also given by some common environmental and design characteristics, such as type of government (presidentialism), ethnicity, language, geographical proximity, authoritarian and democratic regimes, among others. Notwithstanding, the selection of legal systems is also driven by methodological prescriptions, such as, choosing cases in which some variation in the dependent and independent variables are present. In the case of constitutional replacement, the dependent variable has widely varied among all five countries, e.g., Bolivia, Ecuador and Venezuela have enacted four constitutions, Peru has enacted two and Colombia only one constitution since 1946. Moreover, all explanatory variables differ depending on the time and country of analysis. Consider also that all countries have faced periods of democratic and de facto regimes or bumpy fluctuations of economic conditions.

This paper is structured as follows. First a brief overview of some seminal concepts and streams on constitutional change are presented, along with prior insights on constitutional replacement among the five selected countries. The second section presents four hypotheses derived from the previous theoretical analysis. The third section is predominantly methodological as it discusses the selection of cases, the variables included into the analysis and the operationalization and limitations of empirical comparative legal analysis. Finally, results on the determinants of constitutional replacement are presented in the last section.

Why do some constitutions survive for long periods of time, decades, even centuries, while others perish in less than a year? Existing studies refer that environmental and constitutional design features are the leading factors of constitutional endurance. Environmental features allude to political, social and economic exogenous factors, whereas constitutional design factors refer to the specific configuration of constitutional provisions, such as form of State, type of government, constitutional adjudication, and so forth. Although most research has traditionally focused on either constitutional design or environmental features as separate explanatory variables, recent studies have analyzed the impact of both these types of factors on constitutional stability. In the following section, prior insights of constitutional change are presented.

Regarding constitutional design, there is general consensus on the notion that the number of veto players, as well as the level of consent required for a replacement plays a crucial role when political stakeholders decide to replace constitutions (Elkins et al., 2009; Hardin, 2013; Lijphart, 2004; Negretto, 2008, 2012; Pérez-Liñán & Castagnola, 2014; Weingast, 2006). Along these lines, it is argued that if constitutional replacement procedures require higher levels of agreement from a greater number of political actors, constitutions are more likely to endure. Conversely, if the replacement process involves less veto players1, and lower degrees of consent between political actors, constitutions are more likely to be replaced.

Of course, means of constitutional reform do not include only replacement, but more commonly amendment procedures, which generally allow constitutional designers to change specific institutions without altering the overall content of a constitution. Particularly, constitutional amendment procedures are called to have a high impact on constitutional replacement, as the durability of a constitution can be influenced by the number of amendments. In this sense, Lutz (1994) finds that “a moderate amendment rate is conducive to constitutional longevity.” It is worth noting that these assumptions depend not only on how flexible (number of veto players, number of instances and level of consent between players) the amendment rules are (Negretto, 2012), but also on the specific function of constitutional amendments under a specific legal system.

Furthermore, different scholars concede that constitutions are more likely to survive if they include provisions which diffuse political power (Colomer, 2016; Elkins et al., 2009; Negretto, 2008). In this context, the balance that political power entails can be achieved through political institutions such as “bicameralism, executive veto, and federalism” (Negretto, 2008). The underlying argument of this position is that such institutions create stable political environments and therefore a long-lasting constitution. Complementing this hypothesis, Przeworski (1988, p. 36) points out that “constitutions that are observed and last for a long time are those that reduce the stakes of political battles.”

Judicial review also has a paramount effect on the duration of constitutions. Besides being a substantial instrument for checks and balances in democratic States and a useful instrument to correct inferior law, judicial review allows judges to interpret and change the function of constitutional provisions, without having to amend or completely replace them (Ackerman, 2000; Lutz, 1994; Negretto, 2012). Correspondingly, the design of judicial review – whether it is decentralized or centralized, abstract or concrete – would determine the lifespan of written constitutions (Elkins et al., 2009). Indeed, depending on its configuration, judicial review may also strengthen or weaken a constitution.

Constitutional endurance has also been studied from an economical perspective. Principally, renegotiation theorists conceive constitutions as political agreements bargained among a number of parties, which leads to several economic problems, such as, uncertain payoffs, hidden information and reservation prices (Kaplow, 1992). From a law and economics perspective, constitutions should be inclusive, flexible, and specific in order to mitigate such difficulties (Elkins et al., 2009). In this line, constitutional scope – the amount of detail and the number of themes covered by a constitution – has been thought as a determinant of constitutional durability. Nevertheless, empirical evidence has shown contradictory evidence in this regard (Elkins et al., 2009, Negretto, 2008).

Without any doubt, constitutions are profoundly shaped by a wide range of different and interdependent processes. Scholars, for instance, have acknowledged the impact of political, economic and social features on constitutional stability. Elster (1995) emphasizes that constitutional change is meant to occur during extraordinary political moments, through which a political community constructs a new normative system. “To reduce the scope for institutional interest, constitutions ought to be written by specially convened assemblies and not by bodies that also serve as ordinary legislatures. Nor should legislators be given a central place in ratification”, Elster urges (1998, p. 117).

Furthermore, existing studies have reasonably maintained that the duration of constitutions is largely dependent on political regime changes. In this regard, transitions from authoritarian regimes to democratic ones are said to be impossible without new formal and informal sets of arrangements, in the form of constitutions, between government and political opposition (Dahl, 1973; Elkins et al., 2009). Hence, a political regime transition will portray higher probabilities of constitutional replacement. Continuing this idea, as new governors need new legal layouts to develop their policies, constitutional replacement will be more alike when new political leaderships consolidate their power. Additionally, some authors stress the importance of public ratification as a protective factor for constitutional longevity (Elkins et al., 2009).

Likewise, economic conditions determine the durability of constitutions according to some scholars. On the one hand, positive economic growth entails better chances of political stability (Przeworski, 1988). On the other hand, economic crisis may severely destabilize political, social and legal conditions. As a result, studies show that countries with strong economies are more likely to have enduring constitutions, whereas those ones which portray weak economic conditions are prone to constant constitutional replacements (Elkins et al., 2009).

Among the most important social factors, existing literature has taken into account the influence of four elements on constitutional durability: the diffusion effect, historical legacies, ethnicity, and internal and external conflicts. First, the diffusion effect suggests that constitutional replacement in a country “inspires constitutional reform in another” neighboring country (Elkins et al., 2009). Second, historical legacies as determinants of constitutional replacement rely on the fact that “States that have existed for several generations” will have longer constitutions, while younger States will produce less stable constitutions (Ritchie, 2005). Third, ethnicity may determine constitutional stability because it is easier to sustain agreements among homogeneous populations (Sollors, 1986). Finally, Elkins et al. (2009) argue that armed conflicts, whether inter or intrastate belligerences, have been a traditional threat for political systems. In this sense, scholars evidence that defeat in armed conflicts increases the risk of constitutional replacement.

For the purposes of the present study, constitutional replacement is defined as the complete substitution of an expiring constitution and the adoption of a formally labeled new constitution. Unlike other forms of constitutional modification, replacement entails the formal displacement of a precedent constitution. From a functional perspective, Elkins et al. (2009) ideally understand constitutional replacement as a mechanism intended to reform those basic political institutions of a State, as the structure of the State, the form of government, fundamental rights or constitutional adjudication. Complementary, Negretto (2012) suggests that constitutional replacement occurs when certain political events demand for a “new governance structure.” This viewpoint is shared by Adams (2014, p. 281) for whom “constitutions are the ultimate means of building and sustaining a just political order.” Indeed, constitutional replacement implies the incapacity of a State to preserve the structure of a political community and the necessity to refund governance institutions.

From an institutional perspective, constitutions are labeled as permanent sets of norms which organize the State (Hardin, 2003). In this regard, it is undertaken that constitutions are meant to be stable due to the elevated cost of constitutional replacement (Powell and DiMaggio, 2012). Even though there seems to be a settled consensus among constitutional scholars regarding that a central aim of constitutionalism is the entrenchment of constitutional rules, it is impossible to deny the recurrent replacement of constitutions in some parts of the world. Consider the case of Latin America, a region that across history has enacted almost fifty per cent of all constitutions in the world (Elkins et al., 2009).

Legal scholars conceive constitutions as lasting rules, set to establish, organize and guide the political life of a State (Hardin, 2003). In all five countries under study, the empirical reality is that the majority of constitutions have been subjected to frequent revision. How can legal scholars undertake the endurance of constitutions, if they are constantly replaced or simply unobserved? Perhaps this gap between constitutional theory and the practice of constitution-making has tarnished a realistic comprehension of constitutional change in some countries of Latin America (Elkins, Ginsburg, & Melton, 2009; Negretto, 2008).

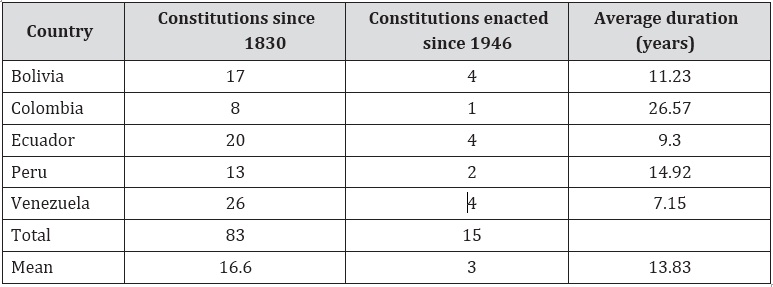

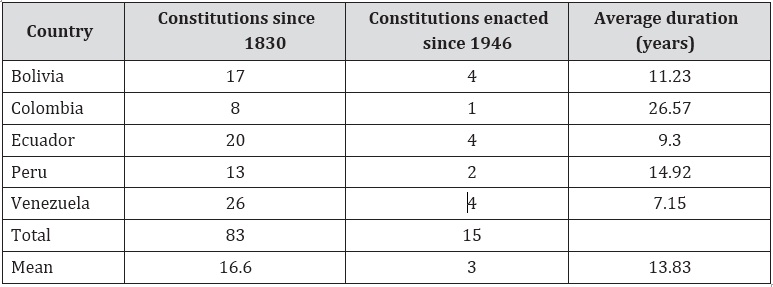

Acrosshistory, Latin American countries haveenacted almost fifty per cent of the total enacted constitutions around the world (Cordeiro, 2008). Particularly, Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela have been frequent constitutional replacers. As depicted in Table 1, eighty-three constitutions were enacted between 1830 and 2016, and fifteen between 1946 and 2016. The number of constitutions enacted since independence ranges from eight, in the case of Colombia, to twenty-six, in the case of Venezuela. In addition, the mean lifespan of constitutions is thirteen point eight years. It is worth noting that constitutional lifetime changes extensively depending on the country. For instance, the Constitution enacted in 1886 in Colombia lasted for 105 years, while the Ecuadorean Constitution of 1945 lasted less than a year.

Source: Political Database of the Americas, Georgetown University.

Constitutions have operated among strikingly different political and economic conditions, as almost all South American countries experienced authoritarian dictatorships and democratic regimes, as well as fluctuating economic conditions. Furthermore, even under democratic regimes, constitutional replacement has not ceased. As shown by Negretto (2008), “anaverage of one constitution was enacted per country” after the third wave of democratization (1978-2016). From a legal point of view, comparative empirical studies are much needed, as practically all the research conducted in the region is based on historical national case analysis (Fortuol, 1942; Mariño, 1998). It is therefore remarkably interesting to study the extent to which political, economic and legal variables determine constitutional replacement across these five legal systems, both from an empirical and comparative perspective.

Based on the preceding discussion, this study mainly tests the four following hypotheses:

H1) First, it is expected that under instable political and economic conditions, the probability of constitutional replacement will increase. In this regard, adverse political and economic conditions may operate as risk factors of constitutional replacement.

H2) Second, it is hypothesized that constitutions which diffuse political power, including institutions such as bicameralism or constitutional review, may tend to last longer than other constitutions.

H3) Third, content wise, it is expected that those constitutions which cover a large number of themes and details might be prone to constitutional replacement.

H4) Finally, following Lutz (1994), it is predicted that constitutional amendment may act as a protective factor of constitutional replacement. In other words, as the number of constitutional replacement increases, the number of con- stitutional replacement will tend to decrease.

Case selection

Following the functional method (Zweigert and Kötz, 1992), the selection of legal systems responds to praesumtio similitudinis, an assumption that advocates for the commonalities of the cases that are included in the sample and the universality of certain legal ideas. This claim might be appropriately translated into the constitutional realm, in which the practice of constitutional replacement in the Andean region has had a somehow similar development (Elkins et al., 2009). Other functional equivalencies are also given by some common environmental and design characteristics, such as type of government (presidentialism), ethnicity, language, geographical proximity, authoritarian and democratic regimes, among others. Notwithstanding, the selection criteria is complemented bysome methodological prescriptions, that is, selecting cases inwhichsome variation in the dependent and independent variables are present. In the case of constitutional replacement, the dependent variable has widely varied among all five countries, e.g., Bolivia, Ecuador and Venezuela have enacted four constitutions, Peru has enacted two and Colombia only one constitution since 1846. Moreover, all explanatory variables differ depending on the time and country of analysis. Consider, for example, that all countries have faced periods of democratic and de facto regimes or bumpy changes of their economic conditions.

Casting the net wide

Comparatively speaking, although functionalism may be appropriate as a

starting point, it may also be insufficient to describe political and

economic interactions.

Furthermore, functionalism proves inadequate, as this research does not seek to find one-size-fits-all solutions. It rather seeks to improve a cross-national understanding of constitutional change, by showing the impact of endogenous and exogenous, legal and non-legal variables on the frequency of constitutional replacement.

As this paper aims at understanding which variables determine the probability of a constitution being replaced, Cox’s proportional hazard regression – a particular type of survival statistical analysis which “assumes that each covariate (independent variable) has a proportional and constant effect on the risk” of constitutional replacement (Negretto, 2012, p. 770) – will be used to analyze data. The extent to which political, economic, and legal factors produce constitutional replacement can be determined through statistical survival analysis. Survival analysis is often employed by political scientists to predict the length of civil wars, the duration of legislative-executive coalitions, or the stability of trade agreements between countries, among other phenomenon. Survival analysis “is a collection of statistical procedures for data analysis for which the outcome variable of interest is time until an event occurs” (Kleinbaum and Klein, 2006, p. 4). This kind of analysis is also employed by physicians or biologists to study which factors increase or decrease the risk of developing mortal diseases or even dying because of them.

Data Collection

Data on constitutional replacement between 1946 and 2016 were gathered on an original database. This database contained 316 observations, which corresponded to 19 constitutions, 15 of which were enacted after 1946. The other four observed Constitutions were enacted in 1945 in the case of Bolivia, 1886 in the case of Colombia, 1922 in the case of Peru, and 1936 in the case of Venezuela. The database contains information on the following explanatory variables:

Outcome

Constitutional Replacement (dependent variable): As previously remarked, constitutional replacement is defined as the complete substitution of an expiring constitution and the adoption of a formally labeled “new constitution.” Both the number of constitutions per country and the time (in number of years) from enactment until replacement were gathered in the database.

Democratic/De facto Political Regime: This variable captured whether constitutional replacement happened when the country under study was ruled by a democratically elected government or a de facto regime (non-democratically elected government). A dichotomous indicator was created to capture democratic and non-democratic governments (1= democratic, 0= De facto).

Economic Situation: This variable captured two continuous indicators. On the one hand the annual percentage growth rate of GDP per capita, and on the other hand, the annual rate of inflation. The first variable was originally gathered by Elkins et al. (2009) based on Prezworski and Curvale’s Database (2005). The second variable was originally gathered by Negretto (2008). Missing information was updated on the basis of the World Bank Databank.

Bicameralism: A dichotomous variable was created to capture whether the enacted Constitution instituted a bicameral legislature or not (1=bicameralism, 0= not bicameral).

Constitutional review: A dichotomous variable was created to capture whether the enacted constitution instituted constitutional review, meaning that the Judiciary or a special body of judges is entitled to control the supremacy of the constitution (1=if constitutional review was stipulated in the constitution, 0=if not).

Length: Representing the total number of words of each constitution. As a constitution includes a higher number of words, it is assumed that it covers more details and themes.

Amendment rate: An indicator of the number of amendments divided by the number of enacted constitutions was included in the analysis.

In this regard, variables b and c strictly refer to political and economic conditions, and variables d, e, f refer to legal determinants because they are directly related with the design of a constitution. Variable g is related to both constitutional design and political practices.

Limitations

Empirical comparative analysis entails several restrictions that might be acknowledged. First, constitutional replacement, although functionally defined as a legal mechanism intended to redesign fundamental institutions, it has produced extensive constitutional change, as well as what some authors have come to label as “cosmetic” change (Sáez, 1994). A “cosmetic” change mainly refers to marginal alterations on formal aspects of the content of a constitution, without major changes on substantive institutions. To illustrate, major changes happened when the 1886 Colombian Constitution was replaced in 1991. Indeed, economic, social and cultural fundamental rights were included on the Constitution. Briefly, among the most important changes, a decentralized form of government was introduced, social, cultural and economic rights were included in the text of the Constitution, and the Constitutional Court was also created. These institutions radically changed the governance structure of the Colombian Government and its influence on the whole society (Uprimny, 2002). Contrariwise, the 1967 Ecuadorean Constitution did not include any major reform to its 1946 predecessor (Salgado 2000). In spite of drastic changes, in the case of Colombia, and “cosmetic” ones, in the case of Ecuador, they are both undertaken as constitutional replacement following the information of the Political Database of the Americas (Georgetown University). This limitation also affects other variables such as bicameralism, constitutional adjudication or amendment, which respond to a generic denomination but may operate distinctively among countries, depending on its institutional configuration.

The second limitation is mainly related with quantitative analysis restrictions. This type of analysis might be effective when examining large sets of cases, but worthless when exploring the intricacies of any particular case, in which qualitative instruments may be required. Finally, a whole set of new variables need to be introduced into the analysis in order to capture the complexity of some social phenomena. In this regard, the variables that were included into the present study were restricted due to feasibility constraints.

In spite of these limitations, empirical comparative analysis helps scholars to examine legal phenomena on a scientific, disciplined, interdisciplinary and systematic basis (Hirschl 2005). In words of William Thomson (1981, p. 80), “when you can measure what you are speaking about and express it in numbers, you know something about it; but when you cannot measure it (…) your knowledge is of the meagre and unsatisfactory kind”. This wisdom was not so long ago exclusively applicable to natural and a selective group of social sciences. Nonetheless, legal researchers have now settled that quantitative approaches are central to legal progress. In the realm of constitutional studies, the usage of quantitative techniques is relatively recent. Consider, for instance, the study conducted by Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton (2009), which puts a new spin on a largely hackneyed constitutional question: why do some constitutions survive longer than others?

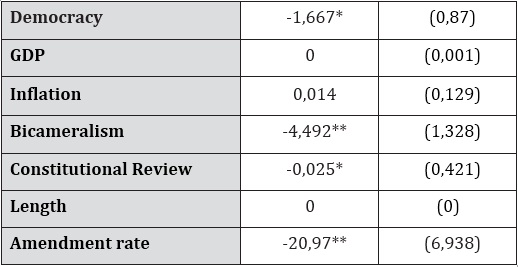

The results of the quantitative analysis are presented in Table 2. When coefficients are positive, variables tend to act as risk factors. Put simply, those positive coefficients show that a particular variable increases the probabilities of constitutional replacement. Conversely, when they are negative, the risk of constitutional replacement decreases. Furthermore, if the value of the coefficient is closer to 0, the impact of the variable on constitutional replacement decreases. A value of 0 therefore identifies a null effect of a particular variable over constitutional replacement. On the contrary if the coefficient is larger than 0, whether positive or negative, the variable will tend to have a larger impact on constitutional replacement. Standard errors are reported between parentheses. As standard errors increase, reliability decreases. Finally, it is worth noting that the asterisk sign (*) represents that the relation between the dependent and independent variable is statistically significant, or stated differently, the correlation between those two relations is not due to chance.

Log pseudo-likelihood 91,083

N=313

Statistically significant at * =p < 0.05; **= p < 0.05

Following the preceding logic, it is necessary to analyze the effect of each variable, and cautiously reject or accept the proposed hypotheses.

Initially, it was hypothesized that adverse political and economic conditions may increase the probability of constitutional replacement. Regarding political regimes, the results confirmed previous expectations. When universally elected officials were in the government, constitutional replacement was less likely to occur. This result is largely backed up by prior literature that links democratic regimes with a larger number of veto players and a relative balance of political power between branches (Dahl, 1973). Although the overall effect of democracy as a political regime is beneficial for the preservation of constitutions, it is worth indicating that in all five countries at least one constitution was replaced when democratic governments were in office. In the case of Colombia (1991) and Bolivia (2009) constitutional replacement did not respond to an immediate regime transition. Indeed, democracy was already adopted since 1957 in Colombia and in 1985 in Bolivia, without a major alteration of the Constitution. In other cases (Ecuador 1978, Peru 1979, and Venezuela 1972) constitutional replacement occurred just amidst the transition from authoritarian or interim governments to democratic regimes (Hagopian and Mainwaring, 2005).

The results concerning economic variables are not consistent with previous theoretical statements. Certainly, it was assumed that negative economic growth and positive economic inflation would increase the probability of constitutional replacement (Przeworski, 1988). According to the analysis, constitutions were replaced despite negative or positive growth of economic indicators. Nevertheless, it should be asserted that on average Colombia depicts the best economic indicators and is also the country which replaced its constitutions less number of times than other countries.

In all examined constitutions, legislatures were organized either as unicameral or bicameral systems, by incorporating a house of representatives or deputies and a senate. Particularly, quantitative analysis shows that when bicameralism is instituted by a constitution, it lessens the probabilities of constitutional replacement. This specific variable has a large preventive effect. According to the arguments discussed in the first section, bicameralism was expected to increase the lifespan of a constitution because it diffuses political power, creating at the same time stable and plural political environments (Negretto, 2008).

Nevertheless, it should be asserted that several bicameral legislatures also functioned when authoritarian or interim regimes ruled countries. This was the case of the 1967’s Ecuadorean Constitution, which instituted the Senate and the House of representatives, and was replaced in 1978. Between 1967 and 1978, Ecuador experienced periods of democracy, but mostly authoritarian regimes. Under these circumstances it is questionable, at the very least, to affirm that bicameralism fomented stable and plural political environments. Despite that fact, bicameralism represents a special institutional layout that hampers political agreements seeking toreplace constitutions. Undeniably, as bicameralism generally entailed the diffusion of power among a larger number of legislative actors, constitutions were better preserved in bicameral systems (Colombia 1886, which was replaced in 1991, Bolivia 1967, which was replaced in 2009). Results are therefore consistent with this line of thought. In spite of the fact that bicameralism decreases the risk of constitutional replacement, only Bolivia (provision 149) and Colombia (provision 104) currently preserve bicameral legislative structures, whereas Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela have unicameral legislatures.

As shown in Table 2, the implementation of constitutional review proceedings slightly reduces the risk of constitutional replacement. In spite of this minor effect, a more significant preventive action was expected, as constitutional review allows judges to examine and evaluate acts and norms originated in the Legislative and Executive branches. Besides being an important instrument for checks and balances in democratic States and a useful instrument to correct law, constitutional review can also reshape political conditions of a country, depending on local features (LaPorta et al., 2004). Consequently, constitutional review was expected to contribute to a better adaptability of constitutions to new policy environments. In accordance to the results, there is no sufficient evidence to assert that the implementation of constitutional review proceedings may extend the lifespan of constitutions.

The effect of constitutional review might be as central as originally predicted because it was only adopted after 1980: Bolivia (1994), Colombia (1991) Ecuador (1978), Peru (1980), and Venezuela (1999). Out of these five constitutions, only the 1991’s Colombian Constitution has been preserved so far. This finding might be correlated with the fact that the Colombian Constitutional Court has been documented as one of the few courts that consistently delivers high-quality judicial decisions and checks the elected political branches in the region (Rodrıguez-Raga, 2011; Uprimny and Villegas, 2004).

Several scholars emphasize that constitutions should regulate fundamental institutions. Otherwise, as its breadth increases, so does the risk of constitutional replacement (Elkins et al., 2009). It is logical to assume that longer constitutions (in terms of number of words), may cover more details and themes than shorter ones. Longer constitutions were expected to be replaced more frequently than shorter ones. Despite this claim, the results show that both short constitutions (Bolivia 1945, which included 9371 words, or Venezuela 1953, which contained 10240 words) and extensive ones (Ecuador 1998, which contained 29282 words) were equally replaced.

Rosenn (1990) notes that Latin American constitutions were generally drafted by ordinary legislatures, instead of constituent assemblies. As a consequence, constitutions were designed as if they were ordinary laws, including ordinary legislative duties. To an extent, this ‘ordinarization’ of constitutions might be illustrated by the length of its text. This claim is not free of contradiction. In fact, all five constitutions enacted after 1990 were drafted by constituent assemblies.

In any case, the length of each constitution does not appear to affect constitutional replacement. It should be remarked, for instance, that as time passes by constitutions are getting longer in the five observed countries (the Ecuadorean 2008 constitution being the longest one with 54684 words).

Regarding amendment procedure2, it was predicted that the risk of constitutional replacement would decrease as the number of amendments increases. In this line of thought, amendments were conceived as mechanisms that allowed the continuity of a constitution without a disruptive effect or such high political costs as constitutional replacement. According to Table 2, amendment rate has a significant effect over constitutional replacement, although not reliable enough when compared to other variables (due to its variability). This effect can be illustrated by the case of the Colombian 1886 Constitution, which endured for 95 years and was amended 36 times. Conversely, the effect of amendment over replacement rests controverted in the case of the Venezuelan 1961 Constitution, which was replaced in 1999, and was amended only twice or the Bolivian 1967 Constitution which endured for 42 years and was amended on five occasions.

Particularly, the case of Colombia was intriguing due to the large number of amendments. When reviewing the Colombian amendment procedure it was noted that both replacement and amendment could be done through the same procedure. In fact, the 1886’s Colombian Constitution did not make any distinction between amendment and replacement, but just provided for the ‘reform’ of the constitution3. As interpreted by Colombian legislators, reform could be partial, being an equivalent of amendment, and total, being an equivalent of replacement. Besides, as provided in the Colombian Constitution, a bicameral legislature was the main actor involved in the reform of the Constitution.

In other cases, Constitutions, which were not amended, never endured more than thirteen years (i.e. Ecuador 1967-1978, Venezuela 1953-1961). Therefore, it should be conceded that those constitutions that are partially amended more frequently are less susceptible of being replaced.

Defying the consensus among constitutional theorists that constitutions are meant to be entrenched, constitutional replacement has been a common practice among the five studied countries between 1946 and 2016. This contribution aimed at bridging the gap between constitutional theory and the practice of constitution-making by providing an empirical account of the determinants of constitutional replacement. According to the analysis hereby presented, variables such as democracy, bicameralism, and amendment rate operate as preventive factors of constitutional replacement. Conversely, the analysis shows that economic variables and the length of a constitution do not affect the probabilities of constitutional replacement.

Democracy, bicameralism and amendment rate increase the life expectancy of a constitution. Particularly, bicameralism and constitutional amendments are found to be good predictors of constitutional endurance among the five studied countries. These findings suggest that legal remedies for constitutional mortality are in the hands of constitutional drafters. Although exogenous factors determine the stability of a political regime, legal institutions could mitigate undesired political effects, especially under highly instable political and economic environments. These findings call for future research on how institutional designs might contribute to the preservation of constitutions, even in spite of adverse political and economic conditions. If one assumes that old-age constitutions are desirable, isolating other characteristics of a long-lasting document could offer critical insights for future constitutional drafters.

Methodologically, this paper attempted to unify empirical and comparative analyses and implement these approaches to reflect on the state of the art of constitutional replacement in the Andean region. Despite its innovativeness, the preceding analysis is unavoidably incomplete mainly because of two reasons. First, political, economic, social and legal variables should be added into quantitative analysis. For instance, type of State (whether federal or unitarian), type of judicial review, or social factors such as ethnicity, heterogeneity or religion might provide a better understanding of constitutional replacement. Second, qualitative methodological techniques, such as expert interviews and surveys, might also enhance comparative constitutional analysis because they portray higher validity and reliability, as experts are acquainted with formal and informal sources of information, which remain inaccessible to other people (Saiegh 2009).

Ackerman, B. (2000). We the People, Volume 2: Transformations: Harvard University Press.

Adams, M. (2014). Disabling constitutionalism. Can the politics of the Belgian Constitution be explained? International Journal of Constitutional Law, 12(2), 279-302.

Adams, L. H. J., & Griffiths, J. (2012). Against comparative method: Explaining similarities and differences. Practice and theory in comparative law, 279-301.

Bernal, C. (2013). Unconstitutional constitutional amendments in the case study of Colombia: An analysis of the justification and meaning of the constitutional replacement doctrine. International journal of constitutional law, 11(2), 339-357

Colomer, J. (2016). The Handbook of Electoral System Choice: Springer.

Cordeiro, J. L. (2008). Constitutions around the world: a view from Latin America. Institute of Developing Economies Paper No. 164.

Dahl, R. A. (1973). Polyarchy: Participation and opposition: Yale University Press.

Elkins, Z., Ginsburg, T., & Melton, J. (2009). The endurance of national constitutions: Cambridge University Press.

Elster, J. (1995). Forces and mechanisms in the constitution-making process. Duke Law Journal, 45(2), 364-396.

Elster, J. (1998). Deliberative democracy (Vol. 1). Cambridge University Press.

Fortoul, J. G. (1942). Historia constitucional de Venezuela (Vol. 1). Editorial” Las Novedades”.

Hagopian, F., & Mainwaring, S. P. (Eds.). (2005). The third wave of democratization in Latin America: advances and setbacks. Cambridge University Press.

Hardin, Rl. “Why a Constitution?’, in Bernard Grofman and Donald Wittman (eds).” International Library of Critical Writings in Economics 166 (2003): 240-261.

Hardin, R. (2013). Why a Constitution? The Social and Political Foundations of Constitutions, 51-72.

Hirschl, R. (2005). The question of case selection in comparative constitutional law. The American Journal of Comparative Law, 53(1), 125-155.

Hooghe, L., Bakker, R., Brigevich, A., De Vries, C., Edwards, E., Marks, G. & Vachudova, M. (2010). Reliability and validity of the 2002 and 2006 Chapel Hill expert surveys on party positioning. European Journal of Political Research, 49(5), 687-703.

Jenkins, S. P. (1995). Easy estimation methods for discrete-time duration models. Oxford bulletin of economics and statistics, 57(1), 129-136.

Kaplow, L. “Rules versus standards: An economic analysis.” Duke Law Journal (1992): 557-629.

Kleinbaum, D. G., & Klein, M. (2006). Survival analysis: a self-learning text. Springer Science & Business Media

King, G., Keohane, R. O., & Verba, S. (1994). Designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research. Princeton University Press.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Pop-Eleches, C., & Shleifer, A. (2004). Judicial checks and balances. Journal of Political Economy, 112(2), 445-470.

Levinson, S. (2011). Constitutional faith: Princeton University Press.

Lijphart, A. (2004). Constitutional design for divided societies. Journal of democracy, 15(2), 96-109.

Lutz, D. S. (1994). Toward a Theory of Constitutional Amendment. American Political Science Review, 88(02), 355-370.

Mariño, L. C. (1998). Apuntes de historia constitucional y política de Colombia. Fundacion Universidad de Bogota Jorge Tadeo Lozano.

Negretto, G. L. (2008). The durability of constitutions in changing environments: ex- plaining constitutional replacements in Latin America: Helen Kellogg Institute for International Studies.

Negretto, G. L. (2012). Replacing and amending constitutions: The logic of constitutional change in Latin America. Law & Society Review, 46(4), 749-779.

Ordeshook, P. C. “Constitutional stability.” Constitutional political economy 3.2 (1992): 137-175.

Pérez-Liñán, A., & Castagnola, A. (2014). Judicial Instability and Endogenous Constitutional Change: Lessons from Latin America. British Journal of Political Science, 1-22.

Pérez-Liñán, A. (2010). El método comparativo y el análisis de configuraciones causales. Revista latinoamericana de política comparada, 3, 125-148.

Powell, W. W., & DiMaggio, P. J. (Eds.). (2012). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. University of Chicago Press.

Przeworski, A. (1988). Democracy as a contingent outcome of conflicts. Constitutionalism and democracy, 59, 63-64.

Rosenn, Keith S. “Brazil’s New Constitution: An Exercise in Transient Constitutionalism for a Transitional Society.” The American Journal of Comparative Law 38.4 (1990): 773-802.

Rihoux, B., & Ragin, C. C. (2009). Configurational comparative methods: Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) and related techniques. Sage.

Ritchie, D. T. (2005). Organic Constitutionalism: Rousseau, Hegel and the Constitution of Society. Journal of Law and Society, 6(36).

Rodrıguez-Raga, J. C. (2011). Strategic Deference in the Colombian Constitutional Court, 1992–2006. Courts in Latin America, 81.

Sáez, M. A. (1994). ¿Por qué no la Segunda República Argentina?. América latina hoy: Revista de ciencias sociales, (7), 81-88.

Saiegh, S. M. (2009). Recovering a basic space from elite surveys: Evidence from Latin America. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 34(1), 117-145.

Salgado, H. (2000). La historia Constitucional de los Derechos Humanos en el Ecuador y sus antecedentes. Revista Ruptura, 1.

Sollors, W. (1986). Beyond ethnicity. New York: Oxford UP, 647-664.

Sutter, Daniel. “Durable Constitutional Rules and Rent Seeking.” Public Finance Review 31.4 (2003): 413-428.

Thomson, W. (1891). Popular Lectures and Addresses, Vol 1. London: MacMillan.

Uprimny, R. (2002). Constitución de 1991, Estado social y derechos humanos: promesas incumplidas, diagnósticos y perspectivas. El debate a la Constitución, 63-110.

Uprimny, R. y García, M. (2004). Corte Constitucional y emancipación social en Colombia. Emancipación social y violencia en Colombia, 463-514.

Weingast, B. (2006). Designing constitutional stability. Democratic Constitutional Design and Public Policy, 343, 347.

Zweigert, K., & Kötz, H. (1992). Introduction to comparative law. Oxford University Press, USA.

1 Veto players are generally defined as those political actors that have the power to decline other actors’ decisions (Tsebellis, 2002).

2 Finally, unlike amendments in the USA, amendments in the five examined countries directly alter and replace the text of the original constitution.

3 In fact, provision 209 stated that, the 1886’s Colombian Constitution ‘may be reformed by a legislative act, discussed and passed after three separate readings in the usual manner by Congress, submitted by the Government to the following Congress for its definite action, and discussed and finally passed in the latter by two-thirds of the members of both houses.’