1. Introduction

The incarceration conditions of prisoners in precarious and overcrowded facilities have sparked a debate on the action of the Brazilian criminal justice system. The prison population tripled between 2000 and 2019, without the corresponding increase of available prison spaces. The media repercussion of several riots resulting in the death of inmates and the accusations before the Inter-American system of Human Rights have revealed the absence of common strategies among the Executive, the Judicial and the Legislative branches to overcome this context of violation of rights.

In the last seven years, the Brazilian Federal Supreme Court - Brazil’s constitutional court - has included several prison-related issues in the trial agenda, such as the degrading conditions arising from overcrowding, the need for the construction of emergency facilities and the provisional release for imprisoned mothers and pregnant women. In 2015, it declared an unconstitutional state of affairs of Brazil’s prison system and ordered the Judiciary and the Executive to take steps, such as the production of information and the release of financial resources to improve the prison system (Supremo Tribunal Federal [STF], 2015). Two years later, the Federal and State Courts of Accounts - external control and support agencies to the Legislature - published a comprehensive institutional assessment of the common challenges for monitoring prison facilities and the application of these resources (Tribunal de Contas da União [TCU], 2017, 2018).

Most of the studies on the topic revolve around the Supreme Court’s ruling about the unconstitutional state of affairs. Part of the studies state in detail the content of the ruling (de Andrade & Teixeira, 2016; Caldas & Lascane Neto, 2016; Pereira, 2017; Jardim, 2018), promote an analysis of the judicial activism of the Court (Garcia, 2014 Meda & Bernardi, 2016b; de Carvalho, de Souza & Santos, 2017; Penna, 2017), a comparative analysis of the Colombian case (dos Santos, Vieira, Damasceno & das Chagas, 2015; Dantas, 2016; Orbage de Britto Taquary & Costa Leão, 2019) or the innovation and the possibility for extension to other fundamental rights violated in the country, such as the right to housing (Meda & Bernardi, 2016a; Duarte & Duarte Neto, 2016). Magalhães (2019b) is pioneering for conducting a dogmatic analysis of the ruling.

More recent studies have discussed the effectiveness of the ruling, as well as the response capacity of the other branches to meet the demands of the Supreme Court (Magalhães, 2019a). In relation to the recommendations made by the Federal Court of Accounts, Vitto (2019) outlines the potentialities and the limits of such recommendations before a highly specialized public policy.

A common feature among these studies is that none of them relates the effects of the constitutional court’s ruling to the performance of the financial and budget control agencies in prison matters.

In this article we intend to analyze this assessment issued by the financial and budget control agencies about the administration of the prison system. For that purpose, we describe the conclusions of the audit reports issued by the Federal Court of Accounts (TCU) in partnership with the state Courts of Accounts about the state prison systems in general, and the prison system of Amazonas state in particular.

The study of the Brazilian case is justified by two main reasons. In the first place, the country is inserted in the Latin-American context of a structural crisis of prison systems and judicial action (Ariza & Torres, 2019). In the second place, one of the specific objectives of the research conducted by Courts of Accounts is to produce data about the prison system and assess the use of the financial resources released after the declaration of an unconstitutional state of affairs and its potential to overcome the violation of human rights.

The main challenge in the analysis of the Brazilian prison system is the lack of dependable information. Much of the information needed regarding the right to life, access to justice and the conditions of prison facilities is barely even produced. Thus, the work of the Courts of Accounts can contribute to the production of consistent information about some of the central elements to judicial and administrative decision-making: the production of information about imprisoned people and their respective maintenance and management costs.

The rulings that the Federal Court of Accounts and the Supreme Court of Brazil have made have been subjected to document analysis. It is the adequate methodology when the examination of materials of different nature is required, that have not yet been analytically treated, looking for new and/or complementary interpretations. Documents are a non-reactive source and, for being originated in a specific historic, economic and social context, depict and provide information about that very same context (Godoy, 1995).

The selection of these rulings was conducted according to two main criteria: (i) the availability in full of these rulings and other documents that compose administrative proceedings and (ii) the novelty of this material, which could be a starting point for new research on the role of Courts of Accounts in the supervision of prison conditions and the management of these resources. For this research paper, we consider the study of Amazonas state an emblematic case, a state that experienced a dramatic prison riot with a high number of casualties and that, according to the audits, has the highest cost per inmate in the country.

In this article I claim that this initial assessment can constitute the informational foundation for the creation of monitoring methodologies and indicators of the prison system in order to secure the fundamental rights of imprisoned people. These measuring instruments can still influence the decisions about public prison policy, the adequacy of prison services according to minimum parameters and of guidelines for legislative, judicial and administrative action.

For that purpose, this article is divided into six parts. The second part will discuss how strategic litigation strategies in the combat against violations in Colombia’s prison system resulted in the Constitutional Court laying down a series of monitoring actions and indicators. Afterwards, we will present the main elements that resulted in Brazil’s Constitutional Court declaring an unconstitutional state of affairs of the prison system. The fourth part of this article will clarify the audit carried out by the Courts of Accounts and the main results regarding the Brazilian prison system and the specific case of Amazonas state.

Subsequently, there will be a discussion of the main results and how this information can contribute to the monitoring of actions that secure the rights of imprisoned people. Lastly, the final considerations point out the contributions and limitations of this article.

2. From the constitutional rights of imprisoned people to the violation of rights in prison facilities

The rights of imprisoned people are provided for by the Federal Constitution as well as by regulations that regulate part of these mechanisms. In Brazil’s Federal Constitution (1988), there are three regulatory groups regarding the deprivation of liberty: (i) regulations that set out duties for police and judicial authorities and rights for citizens who are arrested; (ii) regulations that set out, qualitatively, the admitted sentences and their enforcement mode and (iii) regulations that set out exceptions and suspensions of rights for imprisoned people (Machado, 2020).

Among the regulations of the second group, it is possible to find negative (including prohibited sentences) and positive regulations (specifying how they should be enforced). In addition to the prohibition of torture and inhumane or degrading treatment, the Federal Constitution contemplates a regulation issued specifically to secure the physical and moral integrity of prisoners (art. 5o, XLIX). For Machado (2020), prohibitive regulations have at least three sorts of effects: they impose the appropriate regulation on the legislator, they allow for the control of the regulation’s constitutionality and, moreover, they allow for the accountability of public agencies responsible for their enforcement and supervision. However, both the judicial control of constitutionality and the accountability of agencies depend on the acknowledgement and the action of jurisdictional bodies.

In Colombia, Ariza & Torres (2019) identify three moments of constitutionalization of penitentiary matters by Colombia’s Constitutional Court in the last 20 years. In the first stage, the action of the Court was restricted to the individual demands of imprisoned people who legally protest the subhuman conditions of incarceration. The Court states that, from the moment a person is imprisoned, a special relationship of subordination to the Administration arises, as well as a special regime for the validity of their fundamental rights (Ariza & Torres, 2019, p. 636). It is a doctrine that imposes almost full administrative power on the imprisoned individual, in which the prison administration can modulate or limit their rights to ensure the security and order of the prison facilities (Ariza & Torres, 2019, p. 637).

In the second stage, the disproportionate increase of prison overcrowding between 1995 and 1998 triggered a big number of summary judgements before Colombian judges, a situation examined by the Court that resulted in them declaring an unconstitutional situation of the country’s prison system. The unconstitutional state of affairs is a doctrine applicable to situations in which there exists a “situation of general violation of fundamental rights, that affects a significant number of people and that is a consequence of an institutional disarray of different state entities” (Ariza & Torres, 2019). If, on the one hand, there was important progress to protect prisoners when dealing with the problem of prisons as one of institutional disarray that requires the action of a wide variety of institutions, on the other hand it was not enough to secure the investment of resources in the system before the exponential rise of prison population in the following years (Ariza & Torres, 2019, p. 643).

In 2013 the Colombian Constitutional Court reviewed the strategic litigation actions and returns to the structural analysis of the prison crisis. The Court admitted that the unconstitutional state of affairs of prisons is not a consequence of the lack of prison spaces, but of a “disjointed, reactive criminal policy that is volatile, incoherent, ineffective, without any human rights perspective and subject to national security policy” (Ariza & Torres, 2019, p. 647). The Court thoroughly analyzed the prison system and defined minimum inhabitability criteria, such as minimum accommodation space per inmate, minimum access to water per person, among others. Finally, it established a rule of balance according to which new inmates can only be admitted into the facilities when the number of people entering prison is equal to or lower than the number of people released in the preceding weeks or compatible with the prison facility’s capacity (Ariza & Torres, 2019, p. 650).

The decisions of the Colombian Court are in a stage of implementation, during which indicators are being established to allow for the identification of progress in complying with the court orders and in overcoming the unconstitutional situation (Ariza e Iturralde, 2017). It is worth mentioning that indicators for prisoner numbers and the places they inhabit spark a debate on imprisonment conditions and the minimum human rights guarantees when serving a prison sentence. For example, the use of the concept “prison overcrowding” as an indicator of prison facilities is insufficient to comprehend a myriad of factors that affect the life conditions of imprisoned people that goes beyond the shortage of prison spaces.

As pointed out in Coelho (2020), the debate on prison overcrowding tends to focus on the discussion about number of people versus available space (Coelho, 2020, p. 69). The focus of the debate on prison capacity can include or conceal serious shortcomings in the prison system. For example, a prison facility can comply with the spatial demand of one person per cell, and still be a place of high levels of insalubrity or that does not provide essential services (Coelho, 2020, p. 70). The difficulty of establishing parameters for the capacity limit of a prison facility is the need to consider the demographic composition of the prison population, the psychological effects of imprisonment, the tendency towards violence among inmates, among other elements (Bleich, 1989).

Thus, Bleich (1989) points out that the shortage of services in prison facilities can be related to the use of financial resources. The label “overcrowding” of a facility can lead to the conclusion that there would be a shortage of resources or services. For administration purposes, the lack of standardization of the concept of overpopulation involves an incorrect allocation of public resources and the prioritization of less serious shortcomings of that prison context (Coelho, 2020, p. 66).

As we will further discuss, both the decision of Brazil’s Federal Supreme Court and the audits carried out by control agencies highlight the overcrowding of prison facilities based on an equation of “inmate per prison space”. Nevertheless, there is no sufficient debate on the current existing parameters to secure a minimum of essential public services inside these facilities.

3. The unconstitutional state of affairs of the Brazilian prison system

The Brazilian prison system in composed of 1,394 federal, state and district prison facilities that house 748.000 people, according to data from December 2019 (Conselho Nacional de Justiça [CNJ], 2020a; Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública - Departamento Penitenciário Nacional, 2019a). It is the third-biggest prison population in the world, with a 294% rise between 2000 and 2016. However, the increase of incarcerated people does not match the investments made in the system. This can be observed in the overcrowding context of all federated units in the country (Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública - Departamento Penitenciário Nacional, 2019b). People in preventive custody (without a definitive sentence) amount to 38% of the total prison population. In absolute numbers, the number of people in preventive custody is close to the number of the space shortage of the system (Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública - Departamento Penitenciário Nacional, 2019b; CNJ, 2020b).

Since each state of the Federation has autonomy to organize and administer its prison facilities, the standardization of common information and guidelines becomes a challenge for monitoring of prison conditions. Two of the essential elements for the implementation of public policy - data and evidence about the system, and funding resources and their allocation to fund the system - are not standardized, which negatively affects the decision-making process of the public administrator. There are large shortcomings in the informational systems and in the supervision of prison sentence enforcement, and widespread misinformation about the maintenance costs of each imprisoned person.

This cost lacks standardization among different federated units (TCU, 2017, p. 50). It is estimated that the building costs of a prison facility are elevated, but they amount to only 10% of its total maintenance costs in a 30-year period (TCU, 2017, p. 41). In general, the estimation consists of the sum of the maintenance items (wages, energy and water costs, building maintenance) divided by the number of inmates (Congresso Nacional, 2009). In facilities in which the number of inmates is higher than the number of spaces, the cost will be reduced, but not necessarily due to a more efficient use of the resources, but due to the violation of fundamental rights arising from prison overcrowding. It is estimated that the cost of an imprisoned person in Brazil can be up to four times the average of U$184.25 of the rest of Latin-American countries (Congresso Nacional, 2009).

Since the maintenance costs are high, state governments do not have resources to fully fund prison facilities and they become dependent on the access to resources of the National Penitentiary Fund (Funpen) for funding prison spaces, security equipment and assistance for inmates and former prisoners (Brasil, 1994).

Between 2008 and 2016, Funpen resources were transferred voluntarily from the Federal Government to the states or to other agencies and/or entities (Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública - Departamento Penitenciário Nacional, 2019c). However, between the creation of the Fund and 2015, more than 80% of the available resources were not used. The contrast between the abundance of underused Funpen resources and the context of massive, persisting violation of the fundamental rights of inmates, the structural flaws and the failure of public policy resulted in the declaration of an “unconstitutional state of affairs” of the Brazilian prison system by the country’s Supreme Federal Court (STF, 2015).

The request for non-compliance of fundamental principles ADPF 347 demanded the acknowledgment of a violation of the fundamental rights of imprisoned people and the adoption of several measures to deal with the issues of penitentiary matters in the country. Brazil’s Supreme Federal Court ordered judges and courts to hold preliminary hearings, in order to enable the presence of a detainee before the judicial authority within 24 hours of arrest. Thus, the National Justice Council - control agency for the administrative and financial action of the Judiciary - was appointed to create a computerized register with data about all imprisoned people. The Supreme Court’s justices also decided the release, without any limitations whatsoever, of the accumulated balance of Funpen for improving the penitentiary system.

By imposing mandatory transfers of these resources to state governments, the decision of the Supreme Federal Court resulted in a significant rise of the Fund’s budget execution. Between 2000 and 2018, Funpen’s average annual execution was R$333.11 million. With the implementation of the mandatory transfer, in 2016, the execution was R$1.19 billion (TCU, 2017). Since Funpen resources are federal resources, the use of these funds by state governments, even as part of a mandatory transfer, is subject to the supervision of the Federal Court of Accounts (TCU, 2017). The allocation of resources transferred to state governments must be related to plans previously approved by the agency that administers penitentiary policy - the National Penitentiary Department.

After the Court’s decision, Funpen resources were transferred for the indistinct construction of prison facilities, regardless of the shortage of prison spaces and the cost per inmate in each place. There was no planning for the allocation of resources, since the transfers were carried out a few days after the release of the rules by the federal government (TCU, 2017).

Considering the large volume of federal resources transferred to states without previous planning and the media repercussion of riots in prison facilities, agencies responsible for budget supervision recommended to the Federal Court of Accounts that a coordinated operational audit of Brazil’s prison system was carried out. The audit report includes a comprehensive diagnosis of the shortcomings of penal policy, recognizing the bottlenecks and causes that contribute to the violation of the constitutional principle of dignity of the imprisoned person.

4. Coordinated operational audit of Brazil’s prison system

a. What is a coordinated operational audit?

One of the tools that the Federal Court of Accounts adopts for assessing and monitoring public policy is a coordinated operational audit. An operational audit consists of a method of cooperation between the Federal Court of Accounts and state or municipal Courts of Accounts and/or international external control agencies, in order to look for common solutions through the exchange of information and the adoption of a systemic approach to a topic of common interest (TCU, 2019b). Its results are the production of up-to-date and independent information, and recommended action that optimize the administration capacity, the achievement of goals or the results of public policy (Tribunal de Contas do Estado do Paraná [TCEPR], 2020).

Cooperative audits are a work of supervision that benefits the exchange of knowledge and experience among control agencies, the dissemination of better supervision practices and the honing of the auditors’ professional skills. One type of such audits is the coordinated audit, characterized by having a common core of issues to be analyzed by each supervision agency, that is responsible for adding other matters of interest and issuing independent reports that will later be consolidated (TCU, 2019b).

In general, coordinated audits can be carried out in five stages: (i) preparation, (ii) execution; (iii) report, (iv) evaluation and (v) monitoring. The preparation involves choosing the topic, which demands time, resources and people to negotiate its terms and coordinate actions with teams. A formal agreement is subsequently signed by the legal representatives of the participant institutions in relation to the manner of cooperation. The cooperation aims to host auditors appointed by another participant institution, to share mutual knowledge and to exchange experiences and materials (TCU, 2019b).

The first gathering of the participant institutions is an opportunity for the auditors to meet, to define work plans, to elaborate a planning matrix and a timetable to synchronize the work of different units. In this stage, guidelines are agreed to collect and analyze data, in order to ensure that information collected in a decentralized manner has a high degree of consistency, facilitating the production and analysis of structured information. After carrying out the data collection and analysis for the audit, individual and/or consolidated reports must be drafted (TCU, 2010).

Consolidated reports set out the main conclusions and recommendations from the individual reports. Federal Court of Accounts regulations recommend that it is shared with all interested stakeholders, since it can encourage governments to take preventive and corrective measures, increase public awareness and promote an exchange of knowledge, through the presentation of better practices and experiences (TCU, 2019b).

The last stage is monitoring the implementation of resolutions and supervising the measures adopted by administrators in response to the control agency’s resolutions. The main goal of this stage is to increase the probability of solving the issues identified during the audit, through the enforcement of resolutions or other administrative measures, as well as to find obstacles and difficulties to solve the issues (TCU, 2019b).

These reports are consolidated by the technical units of the Federal Court of Accounts and are later forwarded to the rapporteur of the audit at the Court, who will have to draft an expression containing resolutions and recommendations for the audited agencies to adopt, and both the report and these orientations should be discussed and approved in plenary session at the Court.

b. Why a coordinated operational audit of Brazil’s prison system?

On January 25, 2017, TCU Justice Ana Arraes accepted the suggestion of the National Council of Attorney Generals of Courts of Accounts (CNPGC) and proposed carrying out a coordinated audit of the prison system, in the face of a series of riots in prison facilities that had a big repercussion in the media.

In the same month, at least 115 prisoners died after riots broke out inside the premises of Anísio Jobim penitentiary complex (Manaus/Amazonas), Monte Cristo prison farm (Boavista/Roraima) and Alcaçuz state prison (Nísia Floresta/Rio Grande do Norte). According to Justice Arraes, in a country with more than 1.400 prison facilities, “the lack of a national administration model, the insufficient application of public resources and the non-compliance with functional organization regulations results in the degradation of the prison system, the rise of insecurity and the violation of human rights” (TCU, 2017).

The scope of the coordinated audit of the Federal Court of Accounts with state courts of accounts was to examine the most relevant aspects of the operational and infrastructure administration of Brazil’s prison facilities, as well as to examine the emergency measures that were being taken until then to deal with the riots, administration, costs and supporting technologies associated to the prison system (TCU, 2017). Another object of the audit was the information system of prisons and the application of Funpen resources, that at the time had a balance of more than three billion reals (TCU, 2017).

Funpen is the main source of resources and instruments for funding and supporting activities and programs for the prison system’s modernization and improvement (Brasil, 1994; TCU, 2019b). Since it is a fund linked to the National Penitentiary Department of the Ministry of Justice and Public Security (Depen/MJSP), the use of these resources must be supervised by the Federal Court of Accounts.

The Federal Court of Accounts has taken over the role of coordinating the work of State Courts of Accounts, which has enabled the examination of the most relevant aspects of the operational and infrastructure administration of penal facilities. Moreover, the Federal Court of Accounts was responsible for the audit of federal agencies.

c. What information did the Federal Court of Accounts obtain?

All 26 State Courts of Accounts and that of the Federal District were invited to take part in the coordinated audit by the Federal Court of Accounts, but only 18 Courts responded to the forms about the audit procedures. These Courts of Accounts belong to States whose total prison population amounts to 315.448 people (Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública. Departamento Penitenciário Nacional, 2019a), which represents 42% of the total number of prisoners in the country.

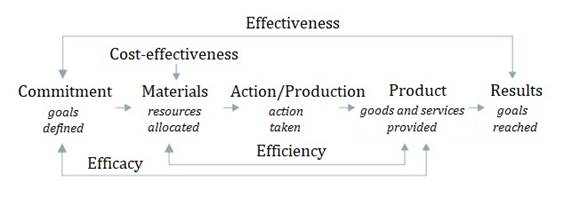

The audit works carried out by the courts of accounts were oriented according to the following topics related to the supervision systems for sentence enforcement, monthly cost per inmate, use of Funpen resources and prison system administration and supervision. The integrated operational audit examined aspects of compliance (with the laws and regulations, according the criteria of legality and legitimacy) and operation (according to dimension of efficiency, efficacy and effectiveness results).

As for legality criteria, the audits examined the compliance with the rules for the use of Funpen resources, with the Law of Penal Enforcement (Brasil, 1984), and with Law 12.714/2012, which sets forth that the data and information about sentence enforcement shall be maintained and updated in a computerized supervision system for sentence enforcement (Brasil, 2012). As for state computerized systems, none of the audited states possess a system compatible with the legal provision, either due to the incompleteness of the available information, or the lack of interoperability among systems of several stakeholders involved in the prison system (TCU, 2017). In 2014, the federal government started procedures to create a web system of data collection that should be inputted by state governments and agencies of the criminal justice system, in order to consolidate a database of all imprisoned people of the country, which is still in implementation phase.

As for the compliance with the regulations of the Law of Penal Enforcement, the Federal Court of Accounts also stresses the context of a shortage of prison spaces in all audited states. Most of the riots recorded between October 2016 and May 2017 took place in prison facilities with a space shortage, that is, 78% of the riot cases happened in overcrowded facilities. According to updated information, the 18 audited states have a prison population of 315.448 inmates, considering convicts and people in pre-trial detention, for a capacity of 178.296 prison spaces. Weaknesses and inconsistencies were found in the registration process of inmates subject to state prison administration, and public defender offices do not possess quality information regarding the quantification of the target audience who could use their services and the details of registered cases by branch of law. There are also indications of public defender offices that have a shortage of staff who work in the area of penal execution (TCU, 2017, p. 54).

The results of the coordinated audit reveal that more than half of the 17 audited States had not calculated the monthly cost per inmate in the preceding three years. When such calculation is carried out, state governments follow their own rules, disregarding the parameters set out by the federal government. The variation of the cost per inmate among states reaches up to 70%, which means, for the Federal Court of Accounts, that there are no criteria for accepting the cost per inmate and that there is a risk of using federal resources in overpriced projects (TCU, 2017, p. 53). Moreover, between 2015 and 2017, almost two billion reals were transferred to the States for improvement of the prison system. The Federal Court of Accounts determined that 74% of the states that received transfers had zero financial execution and did not create any new prison spaces (TCU, 2017). That is, in spite of the significant amount of resources, the executive capacity of governments turned out to be extremely low, and a high amount of these resources remained accumulated without effectively generating prison spaces (TCU, 2018).

As for the interaction among different stakeholders that take part in the implementation of prison policy, the Courts of Accounts tried to assess the existence and the formalization of integrated public prison policy at state level and with the Judiciary and the Public Prosecutor’s Office. They concluded that only one of the states drafted an “Integrated Plan for Improving the Prison System and Complying with the Provisional Measures of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights”, elaborated by the state government of Rondônia, Court of Justice, Public Prosecutor’s Office and Public Defender’s Office. There are four main areas of action, with goals and projects, a definition of responsible units, objective, justification/impact, estimated resources, execution deadline and source of funding (TCU, 2018).

When announcing one of her votes, Justice Ana Arraes concluded that the administration of the prison system requires coordination among stakeholders belonging to the Executive and the Judiciary, the Federal District and Municipalities. And the Federal Court of Accounts, as an external control agency of the federal government, must act in conjunction with the other courts of accounts striving for a solution that involves interdisciplinarity and a multiple institutional coordination among the several government spheres (TCU, 2017).

These conclusions refer to the state prison systems that were audited by control agencies. For this research paper, we consider the study of Amazonas state an emblematic case, a state that experienced a dramatic prison riot with a high number of casualties and that, according to the audits, has the highest cost per inmate in the country.

d. The administration of the prison system in the State of Amazonas

The state of Amazonas is located in the North Region of Brazil, and is the biggest state of the country in terms of territory, with a surface of 1,559,1611.682 km2, equivalent to the territory of France, Spain, Sweden and Greece altogether (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE], 2012). It has an estimated population of 4,144,597 inhabitants, with more than 2 million living in the capital city, Manaus, the most populated city in the North Region (IBGE, 2019). Thus far 65 indigenous groups have been identified living in the territory, meaning that the state holds the biggest indigenous population in the country - almost 170 thousand people (IBGE, 2012).

The state’s prison population has risen exponentially in the last 30 years. In 2003, there were 2,023 imprisoned people, while in 2017 the number of prisoners reached 8,931, which represent 1.2% of the total prison population of Brazil (Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública - Departamento Penitenciário Nacional, 2019b). They are mostly young people between 18 and 24 years old, single, pardos (mixed-race or Afro-Brazilians) or with indigenous features, elementary school dropouts, convicted for drug trafficking and theft (54% of imprisoned people in 2016) (Brasil, 2019b; Amazonas, 2017). In spite of having a small population when compared to the rest of the country, the organization of the prison system of the state is worth noting, which is one of the factors that contributed to the riot that left at least 56 people dead in 2017.

In 1907, Raimundo Vidal Pessoa public prison was inaugurated. It used to house convicted people as well as those without a sentence. For more than 75 years, this public prison was the only prison facility in the city of Manaus. 1982 saw the beginning of the construction of Colônia Agrícola Anísio Jobim prison farm, with the aim of housing convicts that would work producing food during the day and sleep in the premises at night. In 1999, the state government started a series of renovations in the surrounding area of Colônia Agrícola, as a way to meet the demands of the rising number of prison inmates: one unit for people in closed imprisonment, one female unit and temporary detention centers. This set of facilities is what today is known as Anísio Jobim complex (“Compaj”).

In 2013, and in the face of the State’s inability to deal with the demands of the prison population, the state government started to contract, through bidding processes, private companies to operate and administer five prison units. The contracts determine which internal security, food, clothing, hygiene services and medical, psychological and legal assistance would fall under the responsibility of the contractor, while the State would be responsible for supervising those services, for the administration of the prison unit, the external security and inmate statistics (Amazonas, 2017). Afterwards, the state government of Amazonas started administrative procedures to contract private companies to operate and administer six units, out of a total of twenty state facilities (CNJ, 2020a).

On January 1, 2017, a riot broke out inside one of the units administered by contractors (“Compaj”) and twelve employees were taken hostage. The riot left at least 56 inmates dead, and the inmates had access to weapons and ammunition through employees and relatives. Police authorities concluded that there was a conflict between rival criminal factions, a theory later objected by then Minister of Justice Alexandre de Moraes by pointing out that more than half of the casualties had no connection to any factions (PortalG1, 2017). According to the state governor at the time, “there were no saints among the 56 casualties. Overcrowding is a common problem in all States. The resources for building new prison facilities were not released as quickly as people are being imprisoned” (Folha, 2017).

The state government spent resources on the renovation of cells and yards, on wakes and the renovation and adaptation of other facilities to relocate transferred inmates. The state, from being an administrator, became an accused in more than 60 actions for damages for the death of inmates, that amount to more than R$3 million (Amazonas, 2017).

The State Court of Accounts of Amazonas (TCE-AM), in collaboration with an operational audit of its Federal counterpart, determined that, since the breakout of the riot, the stability of the prison environment was reached through concessions and mediations with faction leaders, most of the time illegally. The contractor’s employees obeyed whatever was decided by faction leaders, such as sunbathing times, cell closing times, the entry of food and objects into the facilities and visitors’ overnight stays (Amazonas, 2017).

TCE-AM concluded that the riot at “Compaj” forced the state government to promote the improvement of prison facilities, by acquiring X-ray machines and body scanners and issuing internal rules for visitation, food entry and sunbathing. However, the TCE-AM report pointed out a series of administrative and operational limitations of the state administration, such as a shortage of police officers to supervise the external security of the facilities, the absence of risk management protocols in cases of riots, jailbreaks or mutinies, and the lack of state officials working inside facilities administered by contractors (Amazonas, 2017).

As for the financial and budget administration of the prison system in Amazonas, TCE-AM probed a series of irregularities in the delivery of services and in the supervision of contractors hired for the administration of prison facilities. The assessment revealed at least 21 serious issues, such as overcrowding - more than 288% above their capacity - dire conditions of cells and communal areas, structural weakness of lookouts and walls, shortage of external security staff, lack of basic medication and a lack of employment for inmates (Amazonas, 2017, p. 60).

The cost of the contracts signed with private companies must be calculated into the monthly cost per inmate computed by the state government. Although it is basic administration information, the coordinated audit of the Federal Court of Accounts concluded that there is no uniformity in the parameters adopted in each state of the country, hindering the standardization and monitoring of the effectiveness of these expenses (TCU, 2017). In the case of Amazonas, the calculation for prison facilities administered by contractors is carried out through the division of the yearly paid value by the average number of inmates per year. There is no specific tool and the calculation is carried out manually by each prison unit (Amazonas, 2017).

The monitoring of the compliance of these contracts is also poor. One government official is responsible for the supervision and control of 49 contracts with private companies, whose total value amounts to more than 365 million reals (Amazonas, 2017). The official must verify more than 30 items - from the number of employees per shift to the weight of every meal that the inmates receive - an activity that is carried out manually (Amazonas, 2017). In 14 years of contract duration, there has never been an assessment of the advantages and disadvantages of this contracting modality, and whether the financial resources directly applied to private administration could be better harnessed in other areas, such as intelligence and escape monitoring.

5. Discussion

The fact that the Federal Court of Accounts carried out this coordinated audit represents an innovative path in assessing and understanding the main shortcomings of Brazil’s prison system, and it becomes a relevant tool for the institutional improvement and monitoring of public policy. The Federal Court of Accounts concluded that the shortcomings found in the national prison system are, however, still more far-reaching than the widespread shortage of prison spaces. Among other deficiencies of the sector, there is a lack of quality information for decision-making, bad physical conditions of several prison facilities, individuals imprisoned in facilities that are not adequate for their sentences and the inexistent assistance for inmates in order to prevent crime and guide their return to a life in society (TCU, 2018).

For the Federal Court of Accounts, the institutional design of penal execution agencies requires interdisciplinarity and a multiple institutional coordination among the several spheres of government (TCU, 2017). Nevertheless, the coordination of different stakeholders for the implementation of public policy demands reliable tools to support public officers’ and judges’ decision-making when choosing imprisonment or a sentence other than prison.

Thus, Courts of Accounts oriented their audits according to two essential issues for improving the system: (i) the production of information about inmates and sentence enforcement and (ii) the quantification of the cost of penal facilities per prisoner.

The report of the Federal Court of Accounts points out that the obstacles to the production of statistical data of national level about the prison system are not unknown, but that the solution to the problem has thus far not been actually prioritized (TCU, 2017). The difficulty for the states to adhere to a web system coordinated by the federal government has many causes, such as the unavailability of internet access in prison facilities, the lack of interoperability among systems of different stakeholders and a shortage of technical officials specialized in inputting these systems. One measure recommended by the Federal Court of Accounts to minimize these issues is for the federal government to limit the transfer of Funpen financial resources to state governments that do not input the information systems.

However, this recommendation has a limited scope. Some of the states of the federation that did not even took part in the work of control agencies were not sending information about the inmates they were responsible for before the audit. Apart from the lack of standardization of locally produced information with criteria set out by the federal government, many argue that there is confidential information and security data, whose dissemination can benefit the action of organized groups. These last arguments lack substance, since it is possible to restrict public access to confidential information, and still produce and update relevant content about the conditions of people and facilities that guide the decisions of public administrators and judges.

In this first stage of assessment and recommendations, the Federal Court of Accounts limited itself, in relation to the federal government agencies, to proposing the creation of a course of action by defining deadlines and accountabilities until the completeness of the information system is reached, partnerships with agencies of the Judiciary to produce information and carry out joint studies among the Federation, states, the Federal District and municipalities with the aim of solving internet connection issues in prison facilities. In the second stage of supervision of the recommendations, the control agencies will be able to set out, in a more concrete manner, new measures to be adopted by federal and state governments, taking into account the particularities of each local administration.

As for the quantification of the costs of prison facilities, it should be noted that this cost will be reduced due to incarceration happening in higher numbers than spaces available in each facility, violating prisoners0 fundamental rights. As stated in the report of the Federal Court of Accounts, “ensuring secure, protected and humane prison units is necessarily an expensive undertaking” (TCU, 2017, 2018).

Nevertheless, the difficulties do not lie in the shortage of resources, since a large volume of Funpen resources has been distributed to state governments in the last three years. According to the Federal Court of Accounts, twelve states received $R 383 million for creating prison spaces, but executed only 7.2% of that amount until September 2018 (TCU, 2018). The main causes for the low utilization of available resources were delays in the undertakings’ timetables, lack of planning of the branch, state government administrative deficiencies and federal government slowness in the analysis of processes. And the building projection is not even enough to overcome the potential growth of prison population, let alone to minimize the current shortage of prison spaces.

All stakeholders involved in the prison system interviewed by the Federal Court of Accounts mentioned construction and expansion of prison facilities as a solution to the issue. A big part of state governments do not have the technical capacity to elaborate a project for such complex construction work as the case of a prison facility. Thus, it does not suffice for the federal government to transfer financial resources indistinctly, without assessing the state administration capacity for the execution of these resources and to overcome the dire conditions of these facilities. The transfer of resources to build and expand prison facilities is not a guarantee of an actual creation of prison spaces in the short and medium term, apart from imposing a series of challenges in the improper application of these values by state governments.

In this case, the audit carried out in Amazonas state is worth noting, since apart from the precariousness of the information about people and costs of facilities, there is a difficulty for the state government to supervise the contractors that administer the facilities.

Apart from allocating budget to considerable administration contracts with private companies, there is no integrated plan for health and education actions, as well as legal and social assistance for inmates and former prisoners. Thus, it is evident that a superficial debate on occupancy and the cost of prison facilities are insufficient criteria to assess improvement of prisoner life conditions, as pointed out in Bleich (1989) and Coelho (2020). Despite having the highest cost per inmate in the country, the prison system of Amazonas state has damaged facilities, inadequate food services, provides unsafe water in a rationed manner and reports of mistreatment and torture remain (Mecanismo Nacional de Prevenção e Combate à Tortura [MNPCT], 2020).

Therefore, the attempt to compare the individual cost per inmate among different states without objective criteria does not produce measurable results, as the low cost per unit can reflect less investments in security and essential public services for inmates, apart from concealing behind the figures a context of prison overcrowding. Statements by authorities such as a State governor claiming that “there were no saints” among the 56 dead inmates normalize the trivialization of the cruel and degrading treatment in prison facilities and the lack of competence of public administration in prison matters. Thus, the conclusion of the Federal Court of Accounts audit rapporteur that “Brazil has not yet reached the proper degree of professionalism and efficiency that its population so much expects when it comes to criminal policy and other policies related to the prison system” (Tribunal de Contas da União, 2019a) seems very pertinent.

The reports of the audits carried out by state control agencies and the Federal Court of Accounts mention a series of recommendations for the production of information and the management of penitentiary matters, an institutional assessment that can be a foundation for building methodologies and supervision indicators of the system and that work as guidelines for legislative, judicial and administrative action. The work of Courts of Accounts contributes to an integrated administration perspective, seeking to evaluate transversal and intersectoral mechanisms, apart from offering more support to more systemic and coordinated government action after the declaration of an unconstitutional state of affairs by the Federal Supreme Court.

6. Final considerations

This paper aimed to analyze the assessment carried out by financial and budget control agencies about the administration of the prison system, specifically the audit reports of the Federal Court of Accounts in collaboration with state Courts of Accounts. As support agencies to the Judiciary, these agencies contribute by offering orientations, evaluations and recommendations for public policy improvement.

The audit reports issued by federal and state control agencies reveal that, thus far, there are organizational structures, processes and interactions that hinder Brazil from overcoming the unconstitutional state of affairs of its prison system. There are difficulties to establish minimum parameters for the production of information about inmates and the use of public resources. The resources exist and are available, but there is a shortage of instruments and organizational capacity that assist the decision-making process of government officials for the allocation of these resources.

The data analyzed in this paper suggests that the Courts of Accounts play a relevant part in creating a standard to assess the rights of imprisoned people, through minimum indicators for efficiency and public resource administration that allow for identifying progress and regression in securing incarcerated people’s rights.

The implications of our work are threefold. First, our study contributes to the literature that analyzes the judicialization processes of penitentiary matters. Specifically, the action of courts of accounts is related to the determinations imposed in the Federal Supreme Court’s decision that declared an unconstitutional state of affairs of the prison system. Second, as a practical implication, these results can contribute to the debate on which information is necessary to think of indicators that aim to secure minimum conditions of respect for the human rights of imprisoned people, considering the particularities of each state. Third, they support the creation of coordinated and integrated solutions among different stakeholders that deal with penitentiary matters.

Future studies can be based on this paper in four main ways. First, researchers can expand the analysis of control agency action regarding other elements analyzed in audits. Second, scholars can analyze comparatively the operational audits carried out among other states, as to identify local particularities and elements in common with the national assessment. Third, the analysis can be expanded to other states that did not take part in the audit and apply the same methodology for comparison purposes with other prison administrations. Finally, the study can explore the assessment of coordination and integration of prison system agencies based on the recommendations issued by control agencies.