INTRODUCTION

According to the WHO, obesity is a preventable disease. It is reported that in the year 2016, more than 650 million adults in the world suffered from it (1), with repercussions on the morbidity, mortality and quality of life of the population. This condition requires multidisciplinary management, which in many cases includes surgery. Different surgical techniques have been described to manage obesity. These include vertical sleeve gastrectomy, bypass gastrectomy with Roux-Y reconstruction, adjustable gastric banding (AGB) and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. These techniques have shown better shortterm results in terms of weight loss and less risk associated with obesity-related comorbidities (2).

In the gastric bypass, a stomach reservoir is created, which is anastomosed to the jejunum. An jejunumjejunum anastomosis is then performed, which excludes the remaining stomach, duodenum and proximal jejunum (3) and seeks to reduce the size of the gastric chamber, so that the patient tolerates less food. Less than 1% of bariatric surgeries present complications. The most common complications include anastomotic leakage (0 - 6.1%) and stenosis of the gastro-jejunal anastomosis (3 - 27%) (4). In relation to the surgical technique, the type of suture, the age of the patient and the comorbidities, marginal ulcers have been described, with incidence ranging from 0.6 to 16% (4,5). Other complications are delayed gastric emptying, acute gastric dilation (6) and perforated duodenal ulcer.

Due to the low incidence of perforated duodenal ulcers, there is not much information about their pathophysiological process, diagnosis and management. There are many difficulties in evaluating the remaining stomach, and this is one of the limitations of the surgical procedure. There are some additional diagnostic options such as double balloon endoscopy, retrograde endoscopy however they have not shown good results, so they are not routinely used (7).

CASE PRESENTATION

A 47-year-old male patient with a history of gastric bypass performed in 2013. The patient referred prior to the procedure having performed all preoperative studies including endoscopy, however no longer has the result of it for the report in the medical history. Consulted for a less than 12-hour history of sudden onset, high intensity epigastric pain radiating to the left upper limb and associated with bloodless diarrea and dark (non-melena) stools for a week. He denied having taken any medication at home.

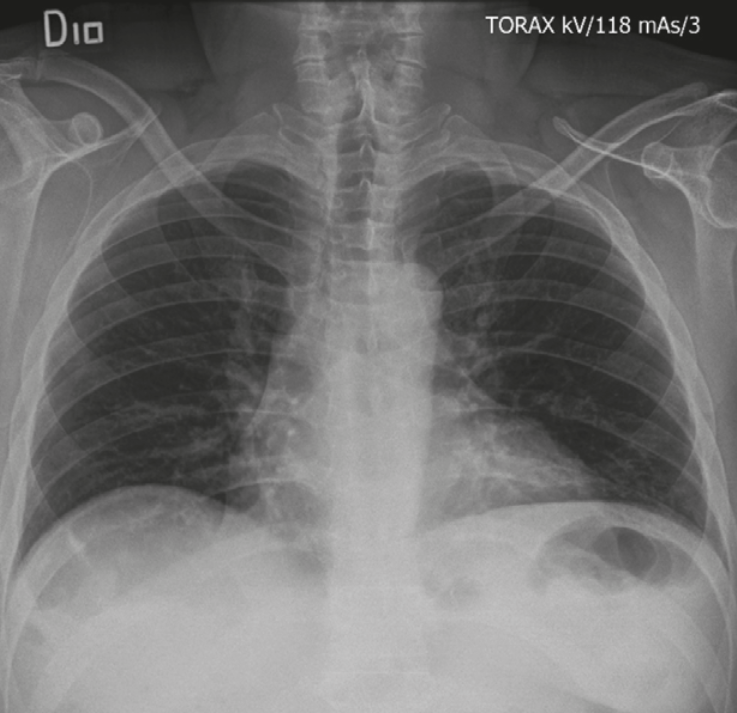

On admission, he presented intense epigastric pain, signs of peritoneal irritation on physical examination, tachycardia without hypotension, weighing 85.7 kg, with previous weight of 110 kg, height 164 cm, which indicated grade I obesity at the time of assessment (BMI: 31.9 kg/m2). A hemogram was taken that showed leukocytosis (17,900) and neutrophilia (90.6%), without anemia (hemoglobin: 15.1); amylasenegative for acute pancreatitis (48), discrete elevation of bilirubin (total bilirubin: 1.41, direct bilirubin 0.27, indirect bilirubin: 1.14); arterial gases (pH:7.353 PCO2: 33.3 HCO3: 14, B-E: -9.9), chest X-ray (Figure 1) with no pneumoperitoneum and abdominal ultrasound with evidence of cholelithiasis and a stone embedded toward the bladder neck as the only abnormal finding. In view of the signs of peritoneal irritation, it was considered appropriate not to perform a contrast abdominal CT scan.

Considering the clinical picture, the findings on physical examination and the paraclinical test results, he underwent diagnostic laparoscopy with suspected hollow viscus perforation. During the procedure, a plastron towards the left hypochondrium was identified, releasing firm adhesions. Since dissection was difficult and not safe, it was decided to convert to midline laparotomy. Entering the abdominal cavity, the gastric antrum, pylorus and first part of the duodenum were identified. In the duodenal bulb, a perforation of approximately 1 cm in diameter was observed in the anterior aspect (Figure 2). A partial omentectomy was performed due to its devitalized aspect. Omentoplasty was performed at the duodenal bulb level in the ulcer area with three 3-0 polypropylene seromuscular stitches, and 500 cc bile peritonitis was drained. The cecal appendix and gall bladder were checked appendicitis or acute cholecystitis were identified.

The patient had an adequate postoperative evolution and was discharged without complications. Followup was performed at 20 days, showing adequate clinical evolution, without signs of early complications. The pathology report was reviewed and found to be negative for malignancy and microorganisms. The patient completed the treatment for eradication of Helicobacter pylori.

Figure 1

Chest x-ray with no evidence of pneumoperitoneum.

Source: Radiology Service San Ignacio’s Hospital

DISCUSSION

Perforated duodenal ulcer following gastric bypass is a rare pathology with a low incidence, not much information about their pathophysiological process, that is difficult to diagnose and has a non-specific presentation, ranging from incipient clinical pictures to peritonitis, shock and life-threatening bleeding (8).

Since 1981 it has been observed that serum gastrin levels do not vary significantly after gastric bypass (9). In a study by Smith et al. (10), acid secretion and vitamin B12 absorption were analyzed in 10 patients undergoing gastric bypass compared to a healthy control group (15 participants). They observed that in the post-operative period of this type of bariatric surgery, patients had less acid production in the gastric reservoir than the control group without anatomical alteration, with a statistically significant difference. However, acid secretion by the remaining stomach was not evaluated.

So far only case reports (3,11,12) have been described, in which relatively similar clinical pictures can be observed, managed with omentoplasty and gastrectomy of the remnant, with satisfactory clinical results. It is a difficult condition to diagnose, due to the low sensitivity of clinical and paraclinical findings. Given the anatomical characteristics of the gastric remnant after the bypass, it is rare to find pneumoperitoneum, which suggests hollow viscus perforation in unaltered anatomical conditions (13).

There are some diagnostic options for evaluating gastric remnant, which is important to know for some intervention. One of the options is the double-balloon endoscopy, which has shown good results, identifying atrophic gastritis (3/4) and atrophic gastritis with metaplasia (1/4). Other options are retrograde endoscopy with a pediatric colonoscope and the percutaneous creation of a tract to the excluded stomach, followed by observation through a gastrostomy. However, they have not shown good results or handling possibilities (9). These studies are not routinely performed, neither are the first line in patients attended in the emergency department with abdominal pain and a history of gastric bypass.

In addition to controlling the perforation, the treatment should include control of risk factors, eradication of Helicobacter pylori and proton pump inhibitors that will favor the regression of these lesions in most cases. Fortunately, a low percentage of patients require other major surgery when fistulas, refractory ulcers or new perforations occur. (14).

Exploratory laparoscopy was used as a diagnostic method, but given the severe inflammatory process, it was decided to convert to open surgery. We consider laparoscopy as an initial approach, through which multiple pathologies can be resolved, including duodenal perforation with the performance of omentoplasty or patches. However, this depends on the experience of the surgeon and the possibility of an approach according to the intraoperative findings.

An early medical and diagnostic approach facilitates a less invasive procedure, with lower associated morbidity-mortality, adequate recovery that allows for continuity of medical management at home, control of risk factors and uncomplicated outpatient follow-up.

CONCLUSION

Perforation of a duodenal ulcer in a patient with a history of gastric bypass is a rare complication, which limits its proper diagnosis. However, in many situations laparoscopy is a useful diagnostic and therapeutic procedure that favors controlling the emergency and should be complemented with the medical management of associated risk factors. (15).