Introduction

Influenza A viruses (IAV) are an important cause of acute respiratory disease in animals and humans (Janke, 2013). Despite evidence of IAV reassortment in other species, swine are key intermediate hosts for the emergence of new viruses (Ma et al., 2009). Several studies have demonstrated transmission of IAV from humans to pigs (Adeola et al., 2010; Forgie et al., 2011), and from pigs to humans (Yassine et al., 2009). IAV transmission between the two species often result in emergence of new strains which spread between both populations (Xu et al., 2011). This bidirectional transmission of IAV has heavily influenced the evolutionary history of IAV in both species. Sustained transmission and rapid adaptation of distinct human viruses after transmission to pigs adds more challenge to the already complicated global epidemiology of IAV in swine with implications in public health and swine health and production (Anderson et al., 2021). Thus, active surveillance of IAV in these populations should be closely monitored for global health concerns (Myers et al., 2007).

Swine IAV (SIAV) infections have significant impact on the affected herd (Cornelison et al., 2018), affecting pig performance, reducing feed conversion ratio, feed intake and weight gain (Olsen et al., 2002; Myers et al., 2007). Although sampling methods to detect SIAV- infected individuals in large populations require a high number of resources (Muñoz-Zanzi et al., 2000), aggregation of samples has been proposed as a cost-efficient tool for detecting diseases in these populations (Rotolo et al., 2018). The effectiveness of pathogen detection in pooled samples is highly dependent on the dilution effect (Arnold et al., 2009); however, several studies have demonstrated a no dilution effect when detecting SIAV in OF by molecular methods (Panyasing et al., 2016; Gerber et al., 2017).

Although SIAV surveillance have been extensively conducted worldwide, few studies have been reported in Colombia (Ramirez et al., 2012). Some potential limitations include technical and economic challenges when testing a significant number of individual samples from a herd (Corzo et al., 2013). However, SIAV monitoring in pigs could be facilitated using oral specimens which are efficient and effective for viral surveillance (Panyasing et al., 2016; Fablet et al., 2017). Therefore, we conducted a prospective observational study for SIAV surveillance at the herd level using porcine OF, providing proof of an efficient, simple, cost- effective, animal welfare friendly and user- friendly sampling tool for IAV longitudinal monitoring in Colombian pig farms.

Materials and Methods

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional committee of the Colombian national swine producer´s association (Porkcolombia) and by the Ethics Committee of Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín (Colombia; Act N°142). Additionally, swine producers provided written consent to participate in the study before sample collection. All samples were collected by trained veterinarians. The study was conducted in compliance with local regulations and international guidelines for ethical conduct in the use of animals in research (https://www.apa.org/science/leadership/care/guidelines).

Study design

A list of farms located in Antioquia province was obtained from Porkcolombia. Candidate sites (owners of these farms) were then contacted by phone to ask willingness to participate and to obtain informed consent for the study. This prospective observational study was conducted in five selected swine farms with past records of influenza-like illness.

The sample size per farm was estimated for disease detection from pooled samples in a large population using the Epitools epidemiology online calculator (Sergeant, 2014), with the following parameters: Aggregate sample size of >20 animals per sample, 80% test sensitivity at pool level (Romagosa et al., 2012), 95% confidence, and 10%. estimated disease prevalence. A sample of two OF per group was required to have a 90% probability to find at least 10% virus prevalence in the sampled subpopulation. An OF sample was described as a pen-based specimen or aggregate sample (Rotolo et al., 2018) collected from a group of >20 animals per pen and/or >20 animals per barn if they were housed individually with close contact among them, i.e., stall-housing in a breeding herd facility.

Sample collection was conducted upon request of the owners or farm technicians, once they suspected a respiratory disease outbreak was occurring in the farm. At the time of the visit, farm production units were inspected to record if there were groups of animals showing clinical signs of influenza-like illness (sneezing, coughing, nasal discharge, difficulty to breath, lethargy, and loss of appetite). Samples were taken from different pigs, including sows, nursery pigs, breeding, and finishing pigs regardless of whether they had clinical signs of respiratory illness or not. The OFs were collected from stall-housed or group- housed pigs at each farm. Groups of animals were selected by simple random sampling using a random number method (Murato et al., 2020). In the stall-housed animals, a number was assigned to each individual and then the aggregate sample was collected hand-holding the rope individually rotating it in 20 randomly selected pigs within the barn. In the group-housed animals, a number was assigned to each pen within a barn and then the aggregate sample was collected holding the ropes at each randomly selected pen or group of animals. In both scenarios, it was guaranteed that resampling of animals did not occur. Samples were collected following the recommendations for the OF collection method previously described (Henao- Diaz et al., 2020; Rotolo, 2017). When the rope was saturated (30 to 60 of min. of chewing time) the fluid was extracted by manually squeezing inside a clean plastic bag. Thereafter, 2 ml of sample was transferred into a tube containing 1 ml of virus transport media (VTM), and transported at 4 °C to the laboratory within 8 hours. Samples were then processed or stored at -80 °C until use. VTM was composed of minimal essential medium with Earle’s salts (MEM; MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), 2x antibiotic-antimycotic solution [penicillin (300 IU/ml; MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), streptomycin (300 lg/ ml; MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), gentamicin (150 lg/ml; MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), amphotericin B (0.75 lg/ml; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA)], in addition to gelatin (0.5%; Amresco, Framingham, MA, USA) and bovine serum albumin (0.5%; MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, MO, USA).

rRT-PCR for IAV detection

The RNA extraction from OF specimens was conducted by using a ZR viral kit (Zymo research, Irvine, CA, USA) following manufacturer´s instructions. The rRT-PCR was performed in a 7500 fast thermocycler (Applied biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) using TaqMan Fast Virus 1-Step Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and specific primers/probe targeting a conserved region of IAV M gene (WHO, 2011). Positive (beta-propiolactone treated pandemic H1N1 virus) and negative controls were included in each run. Running conditions: 1 cycle at 50 °C for 5 min, 1 cycle at 95 °C for 20 s and 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 60 s. Analysis of amplification curves was conducted by using thermal cycler system software. The baseline was set automatically and cycle threshold was visually set to halfway of the exponential phase of the positive control. Samples with a fluorescence cycle threshold value <39 were considered positive.

The RT-PCR assay efficiency and analytical sensitivity (limit of detection) were determined for viral detection from OF samples. Virus spiked OF samples were used to investigate interfering factors in the assay efficiency. Briefly, five OF samples from healthy pigs were tested by adding 50 uL of beta-propiolactone treated pandemic H1N1 virus stock (1 × 106 TCID 50/ml). Samples were tested in two independent replicates by performing 10-fold serial dilutions. Assay efficiency was calculated by Linear regression analysis of the serial 10-fold dilutions using the following formula: (E) = [10 (1 / slope)] - 1 (Stordeur et al., 2002). The limit of detection for the assay was defined as the highest dilution at which all replicates were positive.

Virus isolation

The rRT-PCR IAV positive OF samples were selected for virus isolation. Briefly, confluent monolayers of MDCK cells were prepared in 24- well plates (Costar®, Corning, NY, USA). Cell culture media was removed and monolayers were washed three times with 1X PBS solution (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). Prior to inoculation, sample was filtered using 0.45 um syringe filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Viral inoculum was prepared using 300 ul of sample filtrate diluted in 700 ul of infection media (Decorte et al., 2015). Each sample was inoculated into 2 wells (~0.5 ml/well) and then incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for up to 72 h. Cell cultures were daily observed for cytopathic effects (CPE). If CPE was present, cell culture supernatant was subjected to hemagglutination assay (HA). HA was performed following methods previously described (Killian, 2014). HA-positive cultures were further tested by rRT-PCR for IAV. Cells not showing CPE were exposed to a freeze-thaw cycle (-80 and 37°C) and then tested by HA. Cultures negative for HA were subjected to two additional passages by re-inoculating into fresh confluent MDCK cells. If CPE and HA were negative at 72 h after the third passage samples were considered negative for IAV isolation. Isolates obtained were partially sequenced by sanger sequencing service at an external facility (Macrogen, Korea) and identified using the BLAST tool for Hemaglutinin viral gene (Van den Hoecke et al., 2015).

Statistical analysis

Data were tabulated and classified as positive or negative based on a 39-cycle threshold (ct) cutoff point. A swine group was classified as IAV positive if at least one pen-based OF sample tested positive by rRT-PCR. Descriptive statistics were obtained for each variable according to their data type. Comparison of infection status between groups was tested by Chi squared test. All analyses were performed using the R studio software v3.5.0 (RStudio Team, 2016).

Results

Monitored farms

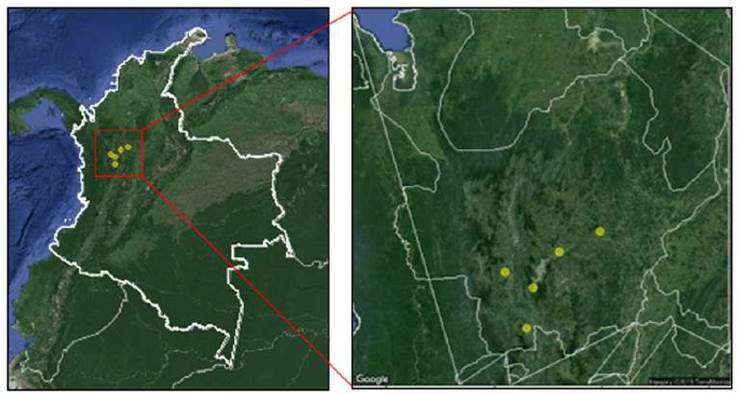

A list of 21 candidate farms was obtained from the national pork producers association. From these, 10 swine producers accepted to participate in the study and five of them were selected for IAV monitoring. These farms were located in the Province of Antioquia (municipalities of Yolombo, Támesis, Betulia, Caldas, and Barbosa; Figure 1). Molecular detection of IAV was carried out in porcine OF collected from January 2014 to December 2017. The farms were farrow to finishing, with common biosecurity practices (disinfection of facilities, quarantine periods for entering personnel and animals, shower and changing clothes at entry, boots disinfection at barn or pen entry). The size of the breeding herd per farm varied from 100 to 500 female pigs. Replacement gilts were obtained from the same farm, except for two farms that had external reposition. Some of the farms had documented serology testing for SIAV but none had records for virus detection by molecular methods. None of the farms vaccinated against SIAV. Environmental conditions, altitude and climate varied from farm to farm; however, these factors were not considered in the analysis.

IAV detection and viral isolation

Five swine farms were monitored for IAV detection. Overall, from the total (n=1,444) OF samples tested, 107 (7.4%) samples were positive to IAV by rRT-PCR (Table 1). Furthermore, Farm I was monitored two times (August 2015 and March 2016) detecting 11 samples positive (12.9%; n=85) to IAV by rRT-PCR. Farm II was monitored three times (October 2015, March and April 2016) detecting -in total- 14 samples positive (11.3%; n=124) to IAV by rRT-PCR. Farm III was monitored 10 times (October and December 2015, February to September 2016, and February 2017) detecting 36 samples positive (5.3%; n=674) to IAV by rRT-PCR. Farm IV was monitored three times (January and August 2014, and February 2015) detecting 4 samples positive (7.1%; n=56) to IAV by rRT-PCR. Farm V was monitored eleven times (from February 2016 to February 2017) detecting 42 samples positive (8.3%; n=505) to IAV by rRT-PCR. We investigated a total of 29 outbreaks of respiratory disease suspected of IAV infection.

We confirmed IAV infection in groups of pigs with and without clinical signs of respiratory disease. The IAV positive samples were found in a wide range of pigs including sows, breeding herds, nursery and finishing pigs at each farm (Table 1). Nine viral isolates were successfully obtained from IAV rRT-PCR positive OF samples after cell culture isolation on MDCK cells. At least one IAV isolate was obtained per farm. Active infection and circulation of IAV was confirmed in all the farms monitored.

No inhibition factors for the rRT-PCR test were present in the specimen (porcine oral fluid) after investigation using spiked OF samples. Good performance of the testing method was found with a limit of detection of 105.5 TCID50/ml observed and a test efficiency greater than 99%.

Discussion

This prospective study provided important information about using OF samples for the detection of IAV in swine herds as an efficient method for disease surveillance and monitoring. This is the first study describing the use of aggregate samples as a screening method to monitor IAV in swine farms over time in Colombia. Our results show how to overcome the common diagnostic challenges under field conditions in swine farms where the testing of a number of individual pigs is limited, the number of pigs per pen differs, and the true prevalence of IAV within a pen is unknown. Therefore, we conclude that monitoring and detection of SIAV from OF pen-based samples in swine herds was successful under the conditions of our study.

Routine surveillance of swine diseases has become more important in recent years as a part of health programs and has increased attention after the impact seen from pandemic diseases; however, collecting appropriate numbers of individual samples can be stressful for the pigs, costly, and labor-intensive (Gerber et al., 2017).

Table 1

Summary of sample collection and IAV rRT-PCR testing results of oral fluids obtained in five monitored pigs farms located in Antioquia province, Colombia (years 2014 to 2017).

Additionally, individual surveillance and molecular testing of large number of individual samples become a challenge for swine producers. The OF sampling method overcomes this limitation, allowing aggregate sample testing, greatly reducing costs, and giving valuable information at a herd level.

Aggregate OF samples can also be collected in the field by trained personnel, demonstrating the easiness of this sampling method. Thus, OF requires minimal training and allows testing large sample numbers providing a non-invasive and useful approach for active surveillance in swine populations in a cost-effectively manner (Panyasing et al., 2016). Our study demonstrates how IAV can be efficiently monitored in swine herds using OF as a screening method. The application of this approach in swine productions in tropical settings can facilitate the detection and monitoring of pathogens of interest for animal and public health.

Virus isolation from samples such as OF becomes challenging sometimes. Several factors contribute to it. Among others, virus inactivation may occur by naturally occurring enzymes or other components present in the OF. Salivary proteins and other components in saliva can significantly inhibit influenza viruses in humans (White et al., 2009). Such components have not been examined in porcine saliva, but experiments have shown inhibitory activity of OF against H1N1 virus (Hartshorn et al., 2006). However, IAV have been isolated in experimentally spiked swine OF (Decorte et al., 2015), which suggests that the components in these specimens do not completely inhibit infectivity and viral growth, and it was confirmed in our study with the successful virus isolation. On the other hand, sensitivity of molecular detection of IAV has been described as higher for OF samples than others sample types (Henao-Diaz et al., 2020).

Interestingly in our study, most pig groups found infected with IAV did not show respiratory disease signs of infection. Therefore, if an infected pig does not show clinical signs of disease it makes it difficult to select and collect appropriate individual samples for disease testing (Grøntvedt et al., 2011; Buehler et al., 2014), highlighting how critical it is to implement detection strategies at the herd level. The results of our study show that OF can be used for IAV detection in swine herds as a routine method with or without clinical signs of respiratory disease. In addition, these specimens can be a good source for testing other pathogens and other laboratory methods such as viral isolation and subsequent subtyping and sequencing of the virus. The applicability of sampling based on OF for surveillance of infections in pig populations have becoming more frequent and well accepted as a valuable tool for detection of many other important swine pathogens ( Trang et al., 2014; Hernández-García et al., 2017; Atkinson et al., 2019; Barrera-Zarate et al., 2019; Henao-Diaz et al., 2020).

The findings of our study provide valuable information regarding the use of OF for molecular detection of IAV in swine farms in one of the main pork producing regions of Colombia. The OF were used to demonstrate the application of an aggregate sampling method as a routine, efficient and cost-effective tool for active surveillance of respiratory viral diseases. Our results also suggested that IAV might represent a common cause of respiratory disease in swine farms. Therefore, routine use of group- based sampling with OF facilitates pathogen detection at the herd level and contributes as an efficient strategy to monitor viral swine diseases of great importance for the pig industry.