1. Introduction

Translations between Brazilian and Spanish-American literary spheres often represent unique spaces of aesthetic experiment, political statement, and theory building. As a creative translator, Augusto de Campos (b. 1931) uses fragmentation, selection, and an anti-critical mode of literary criticism to connect with a wide range of literary traditions. In this article, I analyze his translations of the modernista José Asunción Silva and the vanguardista poets Vicente Huidobro and Oliverio Girondo to map out a different imagined trajectory for Spanish-American poetry that would travel from the linguistic innovations and poetic renovations of Spanish-American modernismo through early avant-garde experimentalism to arrive at concrete poetry without the aesthetic detour of surrealism. In this alternative periodization for Latin American letters, translations between Spanish and Portuguese serve as fields of exchange between different so-called “peripheral” spaces that negate established norms of translation and criticism. Through translation, he draws these Spanish-American poets closer to his own literary canon and emphasizes their impact on the level of language experimentation. After introducing the poet-translator’s statements on Spanish-American poetics and analyzing his translation theories in relation to his poetic strategies of negation, this article centers on Campos’s “untranslation” practice as exemplified by three works he translated from Spanish to understand his participation in an inter-Latin American poetics.

2. Augusto de Campos and the Pablo Neruda Prize for Iberoamerican Poetry

In 2015, Campos won the Premio Iberoamericano de Poesía Pablo Neruda, a prestigious award established in 2004-the centennial of Pablo Neruda’s birth-by the Chilean Council of Art and Culture. The first Brazilian poet to receive this recognition, he names the Chilean poets important to his work in press coverage of the occasion: “I am very grateful that my work has been honored with this prize […] In Chile there are many poets who are important to me, such as Neruda himself, Vicente Huidobro, and Nicanor Parra. I have a great poetic proximity to them” (García, 2015)2. This homage may come as a surprise, given his previous remarks about the Chilean Nobel Prize winner. As recently as 1994, he rebuked Neruda on aesthetic and political grounds. In an interview, Campos associates Neruda with a populist form of surrealism, the “least interesting” of the avant-garde movements, “the one that caused the most trouble” for its “traumatic influence” (A. de Campos & H. de Campos, 2005, p. 175). He further claims that when “Neruda wrote litanies for Stalin” he was one of many “left-wing writers [who] committed great errors” (p. 176), “an opportunist [who] had great benefits from his fidelity to the Soviet Union” (p. 177)3. In light of these prior comments, we can read his statement of “importance” differently: Neruda served Campos as an important counter-example.

The Pablo Neruda prize therefore invites a re-reading of Campos’s previous engagements with Spanish-American literatures. I understand his translations from the 1970s and 1980s of other Spanish-American poets as a partial reconciliation-a different staged encounter-between the aesthetic championed by Neruda of using surrealistic, emotionally evocative images to pursue political ends and the visual, pared down approach that marks concrete poetry and creates political impact through an estrangement from language. Campos was not alone in regretting the lack of mutual reading between these two poetic traditions; Octavio Paz, describes the two fields of production as “simultaneous, coinciding, and nevertheless, totally independent […] absolutely incommunicado” (Paz, 1967/1994, p. 70) 4. If Brazilian and Spanish-American poets have not mutually ignored one another-or rejected, as in the case of Campos with Neruda-by examining translations, we may see another form of mutual influence. When he translates from Spanish to Portuguese, Campos chooses a lesser-known modernista in José Asunción Silva5 and two non-surrealist vanguardista poets Huidobro and Girondo. I posit that his translation practices of selection, fragmentation, and negation allow him to perform both conciliation and divergence between diverse strains of Latin American poetics.

3. Brazilian translation poetics and the brothers de Campos

The Brazilian translation field is notably strong; as Thelma Médici Nóbrega and John Milton (2009) have argued, the brothers de Campos “successfully combined their theoretical work on translation and their actual translations in a way that has been unequalled almost anywhere” (p. 257). But their view has its critics: their ideas presume a readership with access to elite, specialized knowledge of literary discourses. Milton (1996) also calls the program they envisioned an “authoritarianism of rupture,” an “imposition on the reader,” and a form of “snobbery towards other ‘ordinary’ translations” (p. 198). In my view, “transcreation,” “untranslation,” and other neologisms that signal a creative, active, visible translation practice offer readers freedom in how to interact with a translation. Yet for Milton, insistence on creative translation represents a failure of the democratic values the brothers de Campos claim to support. Britto (2004) also points out a certain elitist attitude towards readers who “are blind to signifiers / they only see the signified” (p. 325)6. However, the point remains that centrality of language decontextualization for any political or poetic project remains consistent with their works that question established norms of literary discourse.

Both brothers de Campos invent neologisms for translation projects that distance their creative work from other modes of translation in which an invisible translator transparently conveys the source text in a new language-but their practices differ. Haroldo de Campos (1929-2003) coins the term transcriação to label translations with a high level of aesthetic craft and creative intervention7, and his translation practice flows from this theory of transcreation8. Where Haroldo theorizes a total project combining translation, scholarship, and poetry, Augusto frames his critical arguments about translation after the fact, drawing from diverse sources and theorizing in response to his practice. Furthermore, while Haroldo’s translations tend to be completist and expansive, Augusto renders minimalist, condensed, and fragmenting translations that nevertheless make powerful arguments about their source texts. Paulo Henriques Britto (2004) distinguishes Augusto’s approach to translation as “more ludic” than that of his brother (p. 323), and defines his more oblique direction of analysis: rather than translating thematic content, he focuses on formal elements (p. 324)9. While Britto sees literature as accessing the human condition, love, and death, as a creative translator Augusto minimizes those elements as secondary to draw out qualities of verbal artistry10. As we will see in the case of José Asunción Silva, Augusto does not hesitate to eliminate significant portions of a source text to do so.

For Augusto de Campos, this reduction serves to bring something latent in the source text to the forefront-specifically, the elements of experimentation that fit best with his own poetics. As Myriam Ávila (2004) describes, he expresses an aversion to completist translation, or what he calls “traduções-ônibus” (p. 297)11. In “Traduzir, Conduzir, Reduzir” she interrogates his translation work from German and his choice to present a personal and idiosyncratic vision of Rilke: a concrete, technical Rilke (Ávila, 2004, p. 296). Selecting only those pieces that match his priorities as a writer, he makes the active hand of the translator visible. Furthermore, these pieces display a level of craft that places the art of translation as rigorous, primary, and active rather than secondary or passive.

Campos’s insistence on this active, visible, and creative mode of translation could be read through Lawrence Venuti’s formulation in which fluency is associated with invisibility and domestication as opposed to visibility and foreignization. Rebecca Hernández (2010) reads his choices this way, that they “transcend the source text; in this way Campos becomes a visible, recognizable figure in the translated text” (p. 5)12. In my reading, Venuti’s formulation best applies to translations of prose texts, and I see Campos approaching visibility from a different direction. He seeks out a high degree of fluency, but a fluency determined by his own poetics. Additionally, his work differs from the form of visibility Venuti identifies in the “poet’s version,” which associates a poet’s creative choices or changes with an ignorance of the source language. He claims that the twentieth century “poet’s version” as a genre of translation is consistently marked by “the poet’s admittedly self-serving manipulation of the source text and limited-to-no knowledge of the source language” (Venuti, 2011, p. 233). While Campos’s intraduções certainly fit within this twentieth century mode-both for their practices and for his references to Ezra Pound, a recognized model in this translation genre-they typically draw from a deep knowledge of a source language and culture. He bases his extreme fragmentation and editing on an ethical engagement and deep reading of his sources, what Venuti (2011) describes as a call to future translators, “an ethical action that is neither arbitrary nor anarchically subversive, but rather determined to take responsibility for bringing a foreign text into a different situation by acknowledging that its very foreignness demands cultural innovation” (p. 246). Campos develops modes of translation that respond to this call.

4. Augusto de Campos as translator: “prosa porosa” and “intraduções”

Campos’s terms “intradução” and “prosa porosa” both label a series of translation games after the fact, and over the course of his career, these are just two of his translation neologisms. Where “intradução” rejects the translation norm of the “tradução-ônibus” discussed above, “prosa porosa” rejects a norm of literary criticism where translation and literature both become invisible in favor of the self-sustaining discourse of criticism itself.

“Intradução” titles an iconic Campos translation from the troubadour poet Bernart de Ventadorn (Aguilar, 2003, p. 246-8). Working with two boldly distinct fonts, he places the poet’s name in Gothic and his own name in Westminster, a font visually associated with seventies-era computers. Interspersing the original Provençal with his Portuguese, the two fonts mix along with the two versions of the poem, dated 1174 and 1974 respectively. The first lines: “SISE EUÑAONOUS VVEEIJO / ADOMNAMULHER” perform illegibility and repetition: the words are doubled, supplemented with their translation. The untranslation functions as a visual repetition, with a difference of font. The term “Intradução” then became a broader label for other translations based on added visual characteristics and hyper-selectivity, and he includes a section titled “Intraduções” in his poetry collections, starting with VIVA VAIA: Poesia 1949-1979 and continuing to later publications including Despoesía (1994), and Não Poemas (2003)

The term “intradução” appears to be flexible, shifting along with the larger game Campos plays with prefixes, negation, and repetition. For example, in a personal email with scholar Christopher Funkhouser, he both confirms and alters his label “Intraduções” for a section in Não Poemas (2003): “While confirming that this type of work istranscreation, de Campos writes ‘I prefer to call this kind of translation ‘tradução-arte’, deriving the term from ‘futebol-arte’ (art-soccer), used to distinguish characteristic ballet-like Brazilian football’ (Email Oct 2006)” (Funkhouser, 2007, n.p.) 13. Drawing from the “Intraduções” in VIVA VAIA: Poesia 1949-1979, Gonzalo Aguilar (2003) defines his procedure:

Untranslation consists of the application of intersemiotic criteria, which, through visual manipulation, accentuate the iconographic values of the text. The basic procedures of untranslations are: cutting out arbitrary units (not determined by the original framework), using visual criteria, interpretation through typography, retitling, and pastiche (p. 313-4)14.

While these characteristics are apt, especially as descriptors for the larger body of works Campos uses as source texts for his intraduções, I would qualify the assertion that he makes “arbitrary cuts” that are “not determined by the original framework” of the poem. On the contrary, close examination demonstrates that his cuts from the source texts in Spanish America are deliberate and determined by a reading of the source material that centers language experimentation remained central. Not only do his untranslations follow a thread of his own interest-concrete poetry and experimental language games-they also demonstrate that these qualities have been determining, if underlying, factors even in the poetic traditions not traditionally associated with them.

The flexibility of the prefix “in” Campos chooses for his neologism intradução invites readings of these works that both negate and interiorize the relationship between a source text and its untranslation. Aguilar defines the term through opposition: “it plays with ‘translation,’ ‘introduction, the prefix ‘in’ (this ‘in,’ which is opposed to the ‘ex,’ is the interiority of the poem)” (2003, p. 338) 15. Odile Cisneros (2012) reads this prefix differently: “the term (in)tradução […] puns on both prefixes ‘in’ and ‘intra’ and might be rendered in English as ‘un(in)translation,’ to describe a non-translation, an internal, interior, intimate translation that seeks to translate the inner structures of the poem” (p. 26). Both scholars require a multiplicity of prefixes, in expansion, and in opposition, to give a definition to this form of translation; a series of possible pre-fixes and actions are set into motion by the term intradução. This befits the author’s habit of playing with prefixes and negation of norms and definitions in many aspects of his poetics.

Campos uses prefixes and negations to challenge and resist normative definitions of literature and criticism. In “Sem Palavras” (A. de Campos, 1967/2015) he claims the stance of negation and contestation for concrete poetry writ large, writing:

by proclaiming itself “anti-literature,” concrete poetry does no less than make explicit and sharpen the conflict that underlies the essence of poetry, this strange body, uncomfortable and unqualifiable that lives to trouble “literature” and wake up the “literati.” I previously tried to define this conflict […] as a contradiction between the non-discursive nature of poetry and the means (the logical-discursive syntax of prose) it usually employs. This contradiction is evidenced even by the emblematic artifices such as meter and rhyme, which signal some of the first divergences between poetry and literary prose. Concrete poetry is still “anti-literature,” or more precisely, “anti-poetry” by “poetlesses,” “expoets,” or “a-poets,” in another sense: that of a poetry that prefers to define itself in oppositional terms due to the ethical imperative of not confusing itself with that “poetry with a capital P” (more miniscule and without muscle), which the “system” imposes on us (A. de Campos, 1967/2015, p. 106) 16.

Leaving aside for the now the problematic masculinity of this image opposing poetry with a capital P and the more ethically engaged concrete poetry, the point remains: when Campos expands his position in favor of a literature defined by “antonymic terms” to translation, it necessarily alters the presumed relationship between the source and target texts. As with the desire to distinguish concrete poetry from an institutionalized Poetry, his intraduções seek to distinguish themselves from a capital-T translation, easily recognizable as such, normative. Furthermore, his selection of the less definitively antonymical prefix “in”-which only sometimes operates as a negation-relates to other ways the “poetamenos” describes his works with negations including “anti” or “não” or “ex.” While this early essay rejects what he might have called “criticism with a capital C,” it stops short of creating poetic forms of criticism, or using translations of poetry as criticism, which is precisely what he would later do in O Anticrítico with his prosa porosa.

In O Anticrítico (1986), Campos describes the poem-essays that accompany his translations as prosa porosa or “porous prose” to contrast them with the capital-C literary criticism he rejects. These poem-essays analyze, introduce, and offer a pathway into the works he translates. In his introduction “Antes do Anti” (A. de Campos, 1986b), he writes:

I abhor those critics who practice what I’ve called the “dialectic of slander.” They illuminate nothing and refuse to enlighten themselves, too suspicious and resentful of their own cosmic incompetence to understand or create anything new. I’m against those critics. And it is at them that this book of criticism through love and amateurism, criticism via creative translation, directs the arrow of its “anti.” But my goal is different. My goal is poetry, which (from Dante to Cage) is color, sound, the failure of success-it never happens in a lecture about nothing (p. 10)17.

The prosa porosa and the “creative translations” contained in this volume, therefore, accomplish two interrelated goals. As “criticism via creative translation” they offer a corrective blow to literary criticism that no longer concerns itself with the world of literature but rather with its own activity of discourse building. This combination of porous prose criticism with creative translation also represents a form of “love and amateurism” which might be able to “create something new” or at least shine a light on “the failure of success” as he puts it18 .

Campos began to theorize his term “intradução” in relation to his work on a particular poem by e.e. cummings, in which transformation of the visual qualities came first, followed by an interlingual translation from English to Portuguese after the fact. He explores the relationship between the opposing forces of “intertranslation” and “untranslation” contained within his neologism intradução in one of the introductory essays for his translations of E.E. Cummings (1894-1962)19. When defining intradução he refers to Paulo Miranda, a prior Portuguese-language translator of the American modernist who called his work “não-traduçoes” or “non-translations.”

A young poet I admire, Paulo Miranda, […] recognizing the untranslatability of this Cummings poem, had the wisdom to assimilate it through a peculiar form-Borgesian, you could say, recalling Pierre Menard, author of the Quixote. He had it printed in narrow type on a narrow sheet of paper, which followed the verticalization of the text, and he entitled his work: non-translation/no-translation. Less wise than my young friend, I dared attempt an unorthodox recodification of the poem in Dutch Mecanorma font (Spring 152); the “design” of twisted letters seemed to me to accentuate the iconic characteristics of the composition. Motivated by that picto-typographical exercise, and with its support, I reached the point of risking an untranslation (non-translation? internal or interior or intimate translation?) of the text (A. de Campos, 1984/1986a, p. 28-9) 20.

The history and structure invented term signals both a deeply integrated interior “intratranslation” and also a rejection of translation, an “untranslation,” a taboo translation. “Oswald already recommended converting the taboo into totem. The poem-taboo, totemized by the non-translation of Paulo Miranda, gains a new totem in my ‘untranslation,’ which may at least serve as a good introduction to the sensitive microcosm of the poetry of Cummings” (A. de Campos, 1984/1986a, p. 31) 21. In short, Campos only translates cummings from English to Portuguese (interlingual translation) after finding a way to translate his poem visually (intersemiotic translation) into a form that draws on the interpretation of non-semantic signs such as font, page layout, and color. Only after this new aesthetic information has been adduced to the source text does he “dare” to translate semantic material, paying close attention to the proportions of letters, vowels and consonants, the layout, the use of parenthesis to create verticality, and etc.

Figure 1

“so l(a (cummings) (1984)” (A. de Campos, 1996, p. 47) 22.

Image reproduced with permission of the author and Editora Perspectiva. © Augusto de Campos.

Campos titles this version “so l(a” indicating the poem could also be read directly across in an unintelligible mix of languages-recalling the poem “Intradução,” which functions the same way. The title “so l(a” also amplifies the reading of the poem as musical notes, the solfege scale. Laid out horizontally, these two columns of letters would read: “so(l fol)l(ha cai) itude” in Portuguese and “l(a leaf falls)oneliness.” Always printed as a paired set, the work invites the reader to consider the untranslation in relationship with the source poem, emphasizing the translator’s choices and departures from cummings. These alterations include the addition of another set of parentheses, further isolating one letter, the “l” in “solitude,” which can also be read as a numeral “1” in the middle of the poem. He also does not translate “a leaf” as “uma folha” or “a folha” but with the numeral “1” masquerading or doubling as the letter “l.” Choosing these options allows him to preserve the double “ll” in the middle of the poem, the two vertical lines which create the sensation of downward motion so important to the text. While many of his choices do reproduce elements in the source text, the larger intervention-printing his translation as “so l(a” with two versions side-by-side-means that the poem is no longer so solitary, altering its central vision. Rather than a single string of letters, it is a paired set: “loneliness” and “solitude,” English and Portuguese, are mirrored, matched, and answered, two leaves instead of one.

5. Modernismo hispanoamericáno re-read through an intradução concretista

In several cases-including “so l(a” after e.e. cummings-Campos selects poems which already have concrete characteristics, and his translations maintain or amplify the source’s visual elements23. Yet many of his intraduções are not based on concrete source poems; instead, he selects a fragment of another text to transform into a concrete poem. For example, he untranslates the lyric poem “Obra humana” by the Colombian modernista José Asunción Silva (1865-1896) into a concrete version titled “amorse” (1985) in reference to the Morse Code that runs underneath the eight-letter by seven-letter grid, in red.

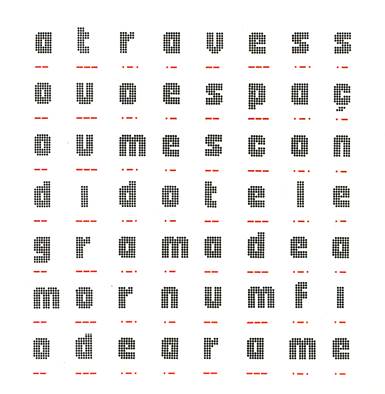

Figure 2

“amorse (josé assunción silva) (1985)” (A. de Campos, 1996, p. 51).

Image reproduced with permission of the author and Editora Perspectiva. © Augusto de Campos

The text of this untranslation-reorganized with breaks between the words-reads: “atravessou o espaço um escondido telegrama de amor num fio de arame [passed through space a hidden telegram of love on a thread of wire]” (p. 51). The interpretive challenge of the dot-style typographic font and the Morse code underneath it makes for multiple mistaken readings. For example, the eye needs time to discern the subtle difference between the letter “l” and the letter “i” because they differ only by the number of dots: the “l” is two dots taller than the “i.” Before making this distinction, the reader could over-determine the “love” theme in the poem, reading the last words as “num flo de ar ame.” This misreading would have meant a bending of Portuguese: first with “flo de ar” into nonsense, and then back into Spanish, where “amé” would only mean “I loved” in Spanish; the Portuguese would be “amei.” A careful reader of Campos’s intraduções might expect to find the language of the source text still present in the original, because the question of language refuses to settle or become singular in his works. In this case, the dot-grid font contributes to the experience of indeterminate language.

In addition to the use of this difficult-to-decode typeface, Campos also inserts another message in Morse code beneath the letters of the fragment of Asunción’s poem. At first glance, the Morse code string might appear to be another translation, another way of representing the same letters. Yet closer examination reveals the Morse code to be merely a repeated series of only four letters: M-O-R-A or MORAMORAMORAMORA repeated underneath each of the seven lines of the poem. This could be read as the word “mora,” close to the word “demora” for delay, respite; it could be deciphered as the verb “morar” to live, to stay, to remain; the most present decoding would be a deformation of the word “amor,” wrapping itself around the grid. Recall that the title is “amorse,” a play on “a morse” referencing the Morse code, but also consonant rhyme or a misspelling that differs by only one letter from “amarse,” to love each other. In this repetition, the hidden Morse code poem recalls the translator’s own concrete poem, “amortemor” (1970), in which the word “amor” is stacked in a triangle against the words “morte” and “temor” in a literal fashion (A. de Campos, 1979/2000, p. 195). When you consider the source text by José Asunción Silva, three stanzas in arte mayor, of which Campos has selected only the final two lines for his concrete untranslation, it becomes even more clear the way his new version is drawing Silva’s work closer to his own.

En lo profundo de la selva añosa

Donde una noche, al comenzar de Mayo,

Tocó en la vieja enredadera hojosa

De la pálida luna el primer rayo,

Pocos meses después la luz de aurora,

Del gas, en la estación, iluminaba

El paso de la audaz locomotora,

Que en el carril durísimo cruzaba.

Y en donde fuera en otro tiempo el nido,

Albergue muelle del alado enjambre,

Pasó por el espacio un escondido

Telegrama de amor, por el alambre.

(Silva, 1990, p. 37)

Notice that only the final two lines of this poem remain in the untranslation. While it may seem unfair to limit the poem so much, to begin his translation where the source text practically ends, the critical edition of this work affirms that even in the source, the last two lines serve as the key to the poem. They were the most edited and contested lines, the verb “pasó” changing tenses, the noun “paso” serving as a title for several versions24. Campos’s untranslation eliminates the setting of the poem by Asunción Silva: there is no longer a jungle, a vine, a moon ray-nor does the modernity of the gas station or the locomotive interrupt this natural landscape. In short, he removed the typical modernista gesture in which the poet crafts a delicate mixture of technological shine and chrome with the infusion of nature with love and meaning, the Romantic poetic setting of the shine of moonlight. The source text entangles the regionalist trope of the jungle vine with the modernist trope of the telegraph wire. This concrete intradução pares down these modernista images, reducing them to the core insight Campos seeks from poetry: an estrangement from language, the breaking down of communication to mechanical pulses. In his version, “love through the wires” is less about naturalizing the telegraph or blending the human experience with the prosthesis of modern telecommunication. To the contrary, it is about distancing the reader from the language through which emotions are expressed, problematizing the human experience as a receptor of signals. Given the almost obsessive repetition of the Morse code string beneath the letters of the poem itself, the transmission is both conveyed and also reduced to meaningless noise.

6. Anti-criticism, anti-boom, and anti-surrealism

Campos may have eliminated the metaphor linking the jungle vine with the telegraph wire from this modernista poem because this image and others like it would be incorporated into surrealism, a poetic tendency he disdained. Marjorie Perloff describes the way both brothers de Campos viewed that branch of avant-garde art:

[S]urrealism was distraction rather than breakthrough. In Latin America, Augusto declares, surrealism, with its “normal grammatical phrases” and the “very conventional structure” that belies its reputed psychic automatism (170), had “a traumatic influence as a kind of avant-garde of consummation!” (175). Haroldo adds, “A kind of conservative avant-garde... All the emphasis on the unconscious and on figurality” (175). [...] The point here is that, whereas the Surrealists were concerned with “new” artistic content-dreamwork, fantasy, the unconscious, political revolution-the Concrete movement always emphasized the transformation of materiality itself (Perloff, 2007, n.p.).

Although Augusto de Campos’s translations do integrate Brazil with Spanish-American poetry, they do not work through the aesthetic qualities of two available transnational and transatlantic poetic movements: late nineteenth-century Spanish-American modernismo or early twentieth-century surrealism as disseminated by the André Breton circle and his associates in Spain and Spanish America. Nor did he seek to build this bridge within the context of the so-called “boom” of the 1960s and its attendant success on the international market as routed through Spain and translated into English. Campos articulates this perspective in “américa latina: contra-boom da poesia,” first published in 1976 in the São Paulo literary magazine Qorpo estranho. Criação intersemiótica (Volume 2, September-December) and later collected in O Anticrítico (Companhia das Letras, 1986). This essay-poem claims25 that the “boom” left little space for poetry, in part because the whole market-driven concept is problematic, but also because within Latin American poetry there is less of a shared space or a common market than in other genres of lettered culture. Citing Octavio Paz, to soften his subsequent critique of Spanish-American poetry, he writes:

o boom da américa latina espanhola

só esqueceu uma coisa

a poesia

(como viu octavio paz)

“acho a palavra boom repulsiva”

disse paz

“não se deve confundir

sucesso, publicidade ou venda

com literatura”

a poesia arte pobre

lixo-luxo da cultura

nunca teve lugar

no mercado comum das letras latino-americanas

(onde só os brasileiros não vendem nada)

[the boom of spanish latin america

only forgot one thing

poetry

(as octavio paz saw)

“I find the word boom repulsive”

said paz

“you shouldn’t confuse

success, publicity, or sales

with literature”

poetry poor art

trash-luxury of culture

never made it

on the free market of latin american letters

(where only the brazilians never sell anything)]

(A. de Campos, 1986b, p. 161)

This final line betrays resentment that, although the whole enterprise may be repulsive, the fact that Brazilians are not enjoying the boom bonanza still irritates. The phrase “lixo-luxo da cultura” describing poetry also references Campos’s poem “LIXO” (1965) in which many repetitions of the word “luxo” or “luxury” are laid out on the page in a sumptuous font printed in gold ink to spell out “lixo” or “garbage” or “waste,” where lots of littler luxuries add up to “garbage” on a large-scale (A. de Campos, 1979/2000, p. 119).

In O anticrítico, Campos is far from rejecting all poetry as garbage; nor does he reject all literary criticism. He names favorite “critics’-critics” (Jakobson, Benjamin, Barthes) and several valued artist-critics (Pound, Valéry, Maiakóvski, Pessoa, Borges, Cage). In fact, he explores the suggestion he attributes to John Cage: “‘a melhor crítica / de um poema / é um poema’ / (Cage)” (A. de Campos, 1986b, p. 16). Each section of this book includes an essay-poem introduction to an author followed by a translated fragment of their work, a fragment selected carefully to illustrate the ideas he emphasizes in his poem essay. In this way, he creates a form of anti-criticism and “untranslation” out of his ideas about some of his favorite touch-stones from many traditions, including the Brazilian: João Cabral Melo Neto and Gregório de Matos receive this treatment; classics Dante, John Donne, and the Rubayat of Omar Khayyam by Edward Fitzgerald; fellow minimalists Emily Dickinson, Duchamp, and John Cage; fellow language innovators Lewis Carroll, Mallarmé, Verlaine, Gertrude Stein, and of course Spanish-American poets Huidobro and Girondo. Yet this essay-poem also indulges in literary nationalism, expressing his vision that: “brazilian poetry / ... / from oswald to concrete poetry / from joão cabral and joão gilberto / ... / created within itself another experimental line / cannibalist and constructivist / that has no parallel in spanish poetry” (A. de Campos, 1986b, p. 162)26.

This vision of the superiority of Brazilian poetry plays a rather unusual role here in an introduction to and an argument for his choice to represent Spanish-American poetry with selections from Vicente Huidobro and Oliveiro Girondo. Campos describes surrealism as an “irritation between us,” between Brazil and Spanish America:

claro, existe um grilo

entre nós e eles:

o surrealismo

(qualquer que seja o nome que lhe dêem)

impregna a massa dos poemas hispano-americanos

de uma insuportável retórica metaforizante

que não questiona a linguagem

a poesia brasileira

(que sofre de outros males)

nunca foi surrealista

[of course, there is an irritation27

between us and them:

surrealism

(no matter the name it goes by)

impregnates the mass of spanish-american poems

with an unbearable metaphorical rhetoric

that does not question language

brazilian poetry

(which suffers from other diseases)

was never surrealist]

(A. de Campos, 1986b, p. 161-2)

Using terms with problematic class and gender valences, the essay-poem stands on the side of those poets who have protected an implicitly elite and masculine sphere of poetry from the disruptive, popular, feminizing force of becoming “impregnated” with the “disease” of surrealism. Despite this critique of the “mass” of Spanish-American poetry for taking the route of surrealism-which here functions as a shorthand for populist sentimentalism-he does want Brazilian readers to access some works from Spanish America: “e no entanto / há algo nessa poesia / q [sic] merecia ser mais conhecido por aqui [and nevertheless / there is something in this poetry / that deserved to be more well-known here]” (A. de Campos, 1986b, p. 161). Huidobro and Girondo emerge as the exceptions, the anti-surrealist “rare pioneers” (A. de Campos, 1986b, p. 162) who pursue a different agenda.

não quer titilar sentimentos

nem subornar más-consciências

poesia de linguagem

e não de língua

qorpo [sic] estranho

[not wanting to titillate feelings

or bribe bad consciences

poetry of language

and not of tongue

strange bodhi]

(A. de Campos, 1986b, p. 163)

The orthographic play in the final line “qorpo [sic] estranho” spelling “corpo” or “body” as “qorpo” draws attention to language as an estranged prosthesis, not of the body, not natural, but materially connected, embodied by all speakers, all users of language. The body or “corpus” of language in this phrase is both living body and corpse, alterable but also rigid. This phrase also titles the short-lived literary journal Qorpo estranho: Revista de criação intersemiótica (1976) where these translations were first published.

7. Vicente Huidobro blends languages through orthographic experiment

Campos translates only a brief portion of the poem Altazor (written between 1919 and 1930, first complete publication in 1931) by the Chilean poet Vicente Huidobro (1893-1948). This cornerstone of the Spanish-American vanguardista movements offers many attractions to the experimental translator for the way it breaks down language into mere sound elements, proving an interpretive challenge to readers and translators alike. This poem includes the phrase that the “poet is a little god” who makes worlds of his own, the translation does not include that celebrated fragment. Although Campos uses a similar term, he does not translate the line “Aquí yace Vicente antipoeta y mago [Here lies Vicente, antipoet and magician]” (Huidobro, 1931/2001, p. 108). Nor does he render in Portuguese the long passage with the repetitive device playing with the phrase “Molino de viento” with multiple rhymes of “viento”-“Molino de aliento / Molino de cuento / molino de intento [Wind-mills / Story-mills / Trying-mills]” (Huidobro, 1931/2001, p. 118-123) -that take the phrase to the point of meaninglessness, of pure language play and sound. Instead of choosing these celebrated moments from Altazor, now representative of the Spanish-language vanguardista tradition, Campos instead selects a portion from the middle of Canto IV, one of the portions published first in French in a literary journal in 1930. Not only does the multilingualism of the source text drive his selection process, he includes the French text as the original rather than the Spanish version eventually published with the entire poem. His translation of Huidobro honors the fragment, the record of the long journey this poem took with its creator, an homage to the “failure” of this work to cohere rather than to the version Huidobro published as an “organic whole” (R. de Costa, 2001, p. 13). Campos translates the selection that confirms the poem as an “open work.”

Due to its fragmentary composition process over several decades, and the way it was published in pieces in different literary magazines and different languages, the poem presents itself as open to multiple readings from multiple readerships (R. de Costa, 2001, p. 24-5). As René de Costa argues, even in the final Spanish version, readers can tell that Huidobro first composed a particular section of the poem in French: even in his translation into Spanish he needed to retain the structure of French words in order to achieve the reference to the musical scale, do re mi (R. de Costa, 2001, p. 19). He bases this argument on the fact that the key word in French, rossignol or “nightingale,” never gets translated entirely into Spanish as ruiseñor. Instead, Huidobro chooses to “Hispanize” the French word by creating a new spelling: “roseñor.” In Campos’s version, presented on the facing page alongside the French in which Huidobro first wrote the poem, his untranslation shows that Portuguese provides a different kind of home for this word-play.

Pero el cielo prefiere el rodoñol

Su niño querido el roreñol

Su flor de alegría el romiñol

Su piel de lágrima el rofañol

Su garganta nocturna el rosolñol

El rolañol

El rosiñol

(Huidobro, 1931/2001, p. 106)

mais le ciel préfère le rodognol

son enfant gâté le rorégnol

sa fleur de joie le romignol

sa peau de larme le rofagnol

sa gorge de nuit le rossolgnol

le rolagnol

le rossignol

(Huidobro, cited in A. de Campos, 1986b, p. 166)

mas o céu prefere o roudonol

seu filho mimado o rourenol

sua flor de alegria o rouminol

sua pele de lágrima o roufanol

sua garganta de noite o roussolnol

o roulanol

o roussinol

(A. de Campos, 1986b, p. 167)

The word “nightingale” is already “rouxinol” in Portuguese, so this untranslation can be read as closer to the French source text than the Spanish version; it posits that Huidobro could have used the help of a Brazilian poet working in Portuguese back in the 1930s to complete his large poem of language experimentation. It furthermore positions itself in relation to a Latin American readership working in between and in the interstitial spaces of multiple European languages all at once.

8. Oliveiro Girondo: untranslating the mero-marrow of negation

In a similar way, Campos translates two poems by Argentine vanguardista Oliveiro Girondo (1891-1967) that allow him to feature advantages to the source text’s poetic project to be found in the Portuguese language. In the case of “El puro no” and “Plexilio” by Girondo, his versions change little, but visually demonstrate the way the Portuguese word for “no”-NÃO-and the Portuguese contraction for “in the”-NO-allow for a cross-language frisson exemplifying the presence of absence featured in both these poems. After the international success of his Poemas para ser leídos en el tranvía (1922) Girondo continued to work at the level of the word in some of his poetry. His later publication En la masmédula (1956), as the title announces, includes many invented and compound words: “mas” and “médula” meaning “more” and “marrow” referring to the expression “hasta la médula” “to the marrow” or “to the bone.” The poem teaches you how to read it, re-introducing the reader to the word “no” by placing it within different verbal tenses: “no” as a noun, “no” as a verb.

El no

el no inóvulo

el no nonato

el noo

el no poslodocosmo de pestios ceros noes que noan noan noan

y nooan

(Girondo, 1956, p. 33)

o não

o não inóvulo

o não nonato

o innão

o não póslodocosmos de pésteos zeros nãos que nãoam nãoam nãoam

e nãoãoam

(A. de Campos, 1986b, p. 169)

These first six lines already expand on and exploit the language games set forth by the source text. By the end, the poem also deploys the same prefix “in” as Campos uses in “intradução” to invoke simultaneous meanings of “intra” and “un,” but this time in a way that relates to the source text, reiterating the use of the prefix “in” for the word “inóseo”:

el yerto inóseo noo en unisolo amódulo

sin poros ya sin nódulo

ni yo ni fosa ni hoyo

el macro no no polvo

el no más nada todo

el puro no

sin no

(Girondo, 1956, p. 34)

o hirto inósseo innão em uníssolo amódulo

sem poros já sem nódulo

nem eu nem cova nem fosso

o macro não não pó

o não mais nada tudo

o puro não

sem não

(A. de Campos, 1986b, p. 169)

When Campos chooses to translate the phrase “el yerto inóseo noo” as “o hirto inósseo innão” he anticipates and creates an echo effect with “inóseo.” “Innão” and “innato” can be read as both non-born and non-innate, or intra-innate. Most importantly these invented words produce the same contradictory issues as the “in” in his neologism intraducões. They set off a chain of potential meanings that include both a greater interiority-“inner-innate” but also “non-innate”-this “no” is both the most interior thing, at the bone, deeper than the bone, intra-bone-but also not-bone, macro, far outside the bone. The source poem already performs the flexibility, the density, the presence and materiality of negation, the “puro no.” By sounding additional multiplicities of meaning within Portuguese, where “in” as a prefix can mean “non” and “intra,” the intradução expands on the source by describing this “puro não” as both a negation and a going deeper into the interior of something.

The poem “Plexilio” contains similar opportunities to exploit the Portuguese language in a multi-lingual context. The title announces the poetic theme as connected to “exile” but also removed from that concept through the neologism “plexile”-a term that could be understood as “plural-exile” or “plexus-exile,” a plurality of exile or a net, web of exile. Formatted on the page as a loose net of phrases, the spatial relationship between words contributes to meaning-making-another example where Campos chooses a concrete poem to translate. The three lines “en el plespacio / … / en el coespacio / … / en el no espacio” (A. de Campos, 1986b, p. 170) translate as “no plespaço / … / no coespaço / … / no não espaço” (171). While the first publication of these translations in Qorpo estranho did not include the source texts, in O anticrítico they appear as facing-page bilingual versions. The reader can enjoy each version and the play between them, in which the negation of “no espacio” is anticipated but also deferred in the Portuguese, where web-space, co-space, and non-space are all negated but also inhabited, from the perspective of a reader of both Spanish and Portuguese. Given the shared realities of exile, plural exile, nets and webs of exiles, experienced by Spanish-American and Brazilian poets, thinkers, and people, evaluating the poem in the context of readers who have access to both languages is a reasonable imagined audience. What does the word “no” mean, for a reader of O anticrítico? Through these translations of Girondo, it can become something new, something that combines the presence of Portuguese, where “no” is “in the” and the absence and negation of the Spanish “no.” Campos uses translation to meditate on negation: his selective, creative translations transform some elements of works across languages in a way that also refuses, rejects, negates other parts of their source texts-but leaves that negation visible. The presence of negation and the way he maintains visible the cuts made in his translations, represent the ethics of his creative untranslations.

9. Conclusions

As a translator, Augusto de Campos fragments source texts to highlight the elements that experiment within language rather than use language to experiment on reality. While he has not retracted his critique of surrealism, accepting the 2015 Pablo Neruda prize, symbolically connects his own work with that tradition, albeit through negation and resistance. By untranslating the surrealist imagery out of one of its precursors, he gives an alternative trajectory for the Spanish-American heirs to modernistas like Asunción Silva and vanguardistas Huidobro and Girondo. To conclude with a coda to this case study of Campos as an untranslator of Latin American poetry, it bears mention that in the same year he was also honored by the Brazilian Ministry of Culture with Orders of Cultural Merit. In his acceptance speech, he expressed pride at receiving this award from then-President Dilma Rouseff whom he had always admired for her democratic activism. The gestures of intercultural dialogue and south-south alliance expressed through his creative translations were undergirded by the former democratically elected government’s support for economic relations that favor south-south connections, political possibilities which may be receding with the ebb of the “pink tide” but which continue to signify in the realm of creative work.