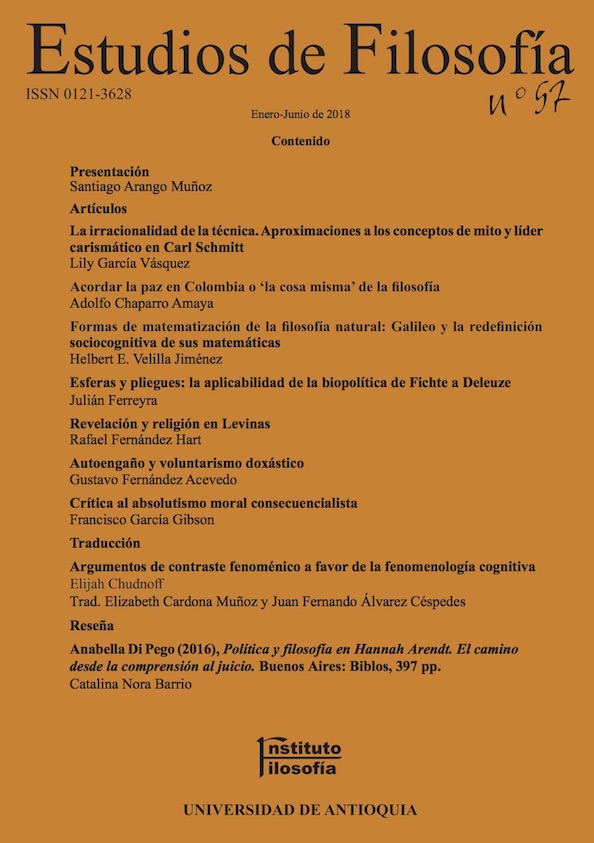

Forms of mathematization of natural philosophy: Galileo and the socio–cognitive redefinition of his mathematics

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ef.n57a04Keywords:

practices, mathematization, geometry, Galileo, natural philosophyAbstract

The topic of this paper is the certainty of mathematics during the 16th and 17th centuries. The specific problem it addresses is that mathematics, in this context, does not provide causal explanations and therefore is not considered to be part of natural philosophy. My working-hypothesis is that the epistemological redefinition of mathematics depends on the practices and on sociocognitive factors; I suggest that there is a redefinition of practices and of the treatment of objects, such as the inclined plane, the balance, the lever and the pendulum. In order to develop this idea, I will firstly analyze the question of the hegemony of natural philosophy over mathematics. Secondly, I will present the relationship between mathematics and natural philosophy, based on the conceptual and practical uses of objects in the Galilean context. Finally, I will point out the practical and epistemological redefinition of mathematics as the study of mathematics applied to motion.

Downloads

References

Aristóteles. (1995). Tratados de Lógica (Organon) II. Trad. Miguel Candel S. Madrid: Gredos.

Barozzi, F. (1560). Opusculum, in quo una Oratio, et duae Quaestiones: altera de certitudine, et altera de medietate Mathematicarum continentur, Padua, Excudebat Gratiosus Perchacinus.

Bertoloni-Meli, D. (2006). Thinking with Objects: The Transformation of Mechanics in the Seventeenth Century. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Biancani, G. (1615). De mathematicarum natura dissertatio. Bolonia, B. Cocchi.

Biagioli, M. (2008). Galileo cortesano: la práctica de la ciencia en la cultura del absolutismo. Buenos Aires: Katz Editores.

Burtt, E. A. (1954). The metaphysical foundations of modern science. Mineola, N.Y: Dover Publications.

Catena, P. (1563). Oratio pro idea methodi. Pud Gratiosum Ðerchacinum (IS), Percacino, Grazioso.

Crombie, A. C. (1990). Science, Art and Nature in Medieval and Modern Thought. London: The Hambledon Press.

Dear, P. (1995). Discipline and Experience: The Mathematical Way in the Scientific Revolution. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Dear, P. (2009). Revolutionizing the Sciences: European Knowledge and its Ambitions, 1500-1700. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Drake, S. (1975a). Galileo’s New Science of Motion. In M. L. R. Bonelli & W. Shea (Eds.), Reason, experiment, and mysticism in the scientific revolution (pp. 131–156). New York: Science History Publications.

Drake, S. (1975b). The Role of Music in Galileo’s Experiments. Scientific American, 232(6), 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0675-98

Drake, S. (1978). Galileo at Work: His Scientific Biography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Drake, S., & Drabkin, I. E. (1969). Mechanics in sixteenth-century Italy: Selections from Tartaglia, Benedetti, Guido Ubaldo, & Galileo (First Edition edition). Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Ducheyne, S. (2006). Galileo’s Interventionist Notion of “Cause.” The Journal of the History of Ideas, 67(3), 443–464.

Feldhay, R. (1998). The use and abuse of mathematical entities: Galileo and the Jesuits revisited. In The Cambridge Companion to Galileo (pp. 80–145). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Finocchiaro, M. (2010). Defending Copernicus and Galileo: Critical Reasoning in the Two Affairs. Heidelberg, London, New york: Springer Science & Business Media.

Galilei, G. (1603a, 1604). Folio 107v. Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale/Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, Firenze.

Galilei, G. (1603b, 1604). Folio 152r. Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale/Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, Firenze.

Galilei, G. (1604). Folio 128r. Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale/Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, Firenze.

Galilei, G. (1891). Le opere di Galileo Galilei : edizione nazionale sotto gli auspicii di sua maesta il re d’Italia. (A. Favaro, Ed.) (Vol. 2). Firenze: G. Barbera.

Galilei, G. (1900). Le opere di Galileo Galilei : edizione nazionale sotto gli auspicii di sua maesta il re d’Italia. (A. Favaro, Ed.) (Vol. 10). Firenze: G. Barbera.

Galilei, G. (1901). Le opere di Galileo Galilei : edizione nazionale sotto gli auspicii di sua maesta il re d’Italia. (A. Favaro, Ed.) (Vol. 11). Firenze: G. Barbera.

Galilei, G. (1960). The Assayer. Trad. Stillman Drake and C. D. O’Malley. in The Controversy on the Comets of 1618. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Galilei, G. (1994). Diálogo sobre los dos máximos sistemas del mundo ptolemaico y copernicano. Trad. Antonio Beltrán. Madrid: Alianza.

Galilei, G. (2003). Diálogos acerca de dos nuevas ciencias. Trad. José San Román. Buenos Aires: Losada.

Galilei, G. (n.d.). De Motu Antiquiora. (R. Fredette, Trans.). Alemania.

Giacobbe, G. (1972a). Francesco Barozzi e la quaestio de certitudine mathematicarum. Physis, Rivista Internazionale Di Storia Della Scienza, XIV(4).

Giacobbe, G. (1972b). Il Commentarium de certitudine mathematicarum disciplinarum di Alessandro Piccolomini. Physis, Rivista Internazionale Di Storia Della Scienza, XIV(2).

Giacobbe, G. (1972c). La quaestio de certitudine mathematicarum all’interno della Scuola Padovana. In Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Storia della Logica, Società Italiana di Logica e Filosofia delle Scienze.

Giacobbe, G. (1973). Alcune cinquecentine riguardanti il processo di rivalutazione epistemologica della matematica nell’ambito della rivoluzione scientifica rinascimentale. La Berio, Bollettino Bibliografico Quadrimestrale, XIII(2–3).

Giacobbe, G. (1976). Epigoni nel Seicento della quaestio de certitudine mathematicarum: Giuseppe Biancani. Physis, Rivista Internazionale Di Storia Della Scienza, XVIII(1).

Giacobbe, G. (1977). Un gesuita progressista nella quaestio de certitudine mathematicarum rinascimentale: Benito Pereyra. Physis, Rivista Internazionale Di Storia Della Scienza, XIX(2).

Hahn, A. J. (2002). The Pendulum Swings Again: A Mathematical Reassessment of Galileo’s Experiments with Inclined Planes. Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 56(4), 339–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004070200048

Henry, J. (2011). Galileo and the scientific revolution: The importance of his kinematics. Galileana, XVIII, 3–36.

Jardine, N. (1988). Epistemology of the Sciences. In C. B. Schmitt, Q. Skinner, & E. Kessler (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy (pp. 685–711). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jesseph, D. M. (1999). Squaring the Circle: The War Between Hobbes and Wallis. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Koyré, A. (1966). Études galiléennes. Paris: Hermann.

Machamer, P. (1978). Galileo and the Causes. In New Perspectives on Galileo (Vol. 14, pp. 161–180). Dordrecht: Reidel Publishing Company. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-94-009-9799-8_5#close

Machamer, P. (1998). Galileo’s machines, his mathematics and his experiments. In The Cambridge Companion to Galileo (pp. 53–79). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Machamer, P., & Woody, A. (1994). A model of intelligibility in science: Using Galileo’s balance as a model for understanding the motion of bodies. Science & Education, 3(3), 215–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00540155

Mancosu, P. (1992). Aristotelian logic and Euclidean mathematics: Seventeenth-century developments of the Quaestio de certitudine mathematicarum. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A, 23(2), 241–265.

Martínez, S., & Huang, X. (2011). Introducción: Hacia una filosofía de la ciencia centrada en prácticas. In Historia, prácticas y estilos en la filosofía de la ciencia. Hacia una epistemología plural. (pp. 5–63). México: UAM-Iztapalapa y Miguel Ángel Porrúa.

Naylor, R. H. (1974). Galileo and the Problem of Free Fall. The British Journal for the History of Science, 7(2), 105–134.

Naylor, R. H. (1977). Galileo’s theory of motion: Processes of conceptual change in the period 1604–1610. Annals of Science, 34(4), 365–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/00033797700200281

Naylor, R. H. (1982). Galileo’s law of fall: Absolute truth or approximation. Annals of Science, 39(4), 384–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/00033798200200491

Ochoa, F. (2013). De la subordinación a la hegemonía. Sobre la legitimación epistemológica de las matemáticas en la filosofía natural en el siglo XVII. Revista Civilizar Ciencias Sociales Y Humanas, 13(25), 125–176.

Pereira, B. (1591). De communibus omnium rerum naturalium principiis & affectionibus: Libri XV. Venetijs,Úndream Muschium.

Piccolomini, A. (1565). Commentarium de certitudine mathematicarum disciplinarum in his Alexandri Piccolominei In mechanicas quaestiones Aristotelis, paraphrasis paulo quidem plenior. Eiusdem commentarium de certitudine mathematicarum disciplinarum: in quo, de resolutione, diffinitione & demonstratione: necnon de materia, & in fine logicae facultatis, quamplura continentur ad rem ipsam, tum mathematicam, tum logicam, maxime pertinentia. Venice: Apud Traianum Curtium.

Remmert, T. (2005). Galileo, God and Mathematics. In Mathematics and the Divine: A Historical Study. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Rodríguez, L. D., & Romero, Á. (2014). Desarrollos galileanos en el campo de la estática: una posible contribución a la enseñanza. Revista Física Y Cultura, 1(5). Retrieved from http://revistas.pedagogica.edu.co/index.php/RFC/article/view/2602

Romo, J. (1985). La física de Galileo. La problemática en torno a la ley caída de los cuerpos. Universidad de Barcelona, Barcelona.

Roux, S. (2010). Forms of Mathematization (14th-17th Centuries). Early Science and Medicine, (15), 319–337.

Salvia, S. (2014). Galileo’s Machine: Late Notes on Free Fall, Projectile Motion, and the Force of Percussion (ca. 1638–1639). Physics in Perspective, 16(4), 440–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00016-014-0149-1

Schaffer, S. (1988). Wallifaction: Thomas Hobbes on school divinity and experimental pneumatics. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A, 19(3), 275–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/0039-3681(88)90001-5

Schöttler, T. (2012). From Causes to Relations: The Emergence of a Non-Aristotelian Concept of Geometrical Proof out of the Quaestio de Certitudine Mathematicarum. Societate Si Politica, 6(2), 29–47.

Shea, W. (1998). Galileo’s Copernicanism: the science and the rethoric. In The Cambridge Companion to Galileo (pp. 211–243). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Swerdlow, N. (1998). Galileo’s discoveries with the telescope and their evidence for the Copernican theory. In The Cambridge Companion to Galileo (pp. 244–270). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Van Dyck, M. (2006). An archaeology of Galileo’s science of motion. Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium.

Velilla, H. (2015a). El debate sobre la certeza de las matemáticas en la filosofía natural de los siglos XVI y XVII (De quaestio de certitudine mathematicarum). Saga - revista de Estudiantes de Filosofía, 16(28), 12–25.

Velilla, H. (2015b). Las matemáticas de los siglos XVI y XVII en la historiografía científica contemporánea. Revista Colombiana de Filosofía de La Ciencia, 15(31), 83–104.

Wisan, W. (1974). The new science of motion: A study of Galileo’s De motu locali. Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 13(2–3), 103–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00327483

Wisan, W. (1977). Mathematics and Experiment in Galileo’s Science of Motion. Annali dell & apos; Istituto E Museo Di Storia Della Scienza Di Firenze, 2(2), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1163/221058777X01361

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

Categories

License

Copyright (c) 2018 Helbert Velilla

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

1. The Author retains copyright in the Work, where the term "Work" shall include all digital objects that may result in subsequent electronic publication or distribution.

2. Upon acceptance of the Work, the author shall grant to the Publisher the right of first publication of the Work.

3. The Author shall grant to the Publisher a nonexclusive perpetual right and license to publish, archive, and make accessible the Work in whole or in part in all forms of media now or hereafter known under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoCommercia-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0), or its equivalent, which, for the avoidance of doubt, allows others to copy, distribute, and transmit the Work under the following conditions: (a) Attribution: Other users must attribute the Work in the manner specified by the author as indicated on the journal Web site;(b) Noncommercial: Other users (including Publisher) may not use this Work for commercial purposes;

4. The Author is able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the nonexclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the Work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), as long as there is provided in the document an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal;

5. Authors are permitted, and Estudios de Filosofía promotes, to post online the preprint manuscript of the Work in institutional repositories or on their Websites prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (see The Effect of Open Access). Any such posting made before acceptance and publication of the Work is expected be updated upon publication to include a reference to the Estudios de Filosofía's assigned URL to the Article and its final published version in Estudios de Filosofía.

Io suppongo (et forse potró dimostrarlo) che il grave cadente naturalmente vada continuamente accrescendo la sua velocità secondo che accresce la distanza dal termine onde si partì […]

Io suppongo (et forse potró dimostrarlo) che il grave cadente naturalmente vada continuamente accrescendo la sua velocità secondo che accresce la distanza dal termine onde si partì […] Supongo (y tal vez pueda demostrarlo) que el grave que cae naturalmente va aumentando continuamente su velocidad a medida que aumenta la distancia al punto desde donde partió.

Supongo (y tal vez pueda demostrarlo) que el grave que cae naturalmente va aumentando continuamente su velocidad a medida que aumenta la distancia al punto desde donde partió. Sit ut ba ad ad, ita da ad ac, et sit be gradus velocitatis in b, et ut ba ad ad, ita sit be ad cf; erit cf gradus velocitatis in c. Cum itaque sit ut ca ad ad, ita cf ad be, erit etiam ut [quadratum] ca ad [quadratum] ad, ita [quadratum] cf ad [quadratum] be: ut autem [quadratum] ca ad [quadratum] ad, ita ca ad ab; ut igitur ca ad ab, ita [quadratum] cf ad [quadratum] be: sunt ergo pun[c]ta e, f in parabola.

Sit ut ba ad ad, ita da ad ac, et sit be gradus velocitatis in b, et ut ba ad ad, ita sit be ad cf; erit cf gradus velocitatis in c. Cum itaque sit ut ca ad ad, ita cf ad be, erit etiam ut [quadratum] ca ad [quadratum] ad, ita [quadratum] cf ad [quadratum] be: ut autem [quadratum] ca ad [quadratum] ad, ita ca ad ab; ut igitur ca ad ab, ita [quadratum] cf ad [quadratum] be: sunt ergo pun[c]ta e, f in parabola.

El punto central de este argumento es que BE y CF representan los grados de velocidad en B y C. Aquí Galileo sostiene que y CF será el grado de velocidad en C. Según

El punto central de este argumento es que BE y CF representan los grados de velocidad en B y C. Aquí Galileo sostiene que y CF será el grado de velocidad en C. Según  será

será

es multiplicar un número entero por 60 y luego añadir un número menor que 60.

es multiplicar un número entero por 60 y luego añadir un número menor que 60.  la primera columna que se encuentra en negrita se debe a que es una anotación con lápiz realizada después de los datos escritos en la tercera columna, y representa la regla correcta 1, 4, 9, 16…64 sobre el crecimiento de las distancias medidas. En

la primera columna que se encuentra en negrita se debe a que es una anotación con lápiz realizada después de los datos escritos en la tercera columna, y representa la regla correcta 1, 4, 9, 16…64 sobre el crecimiento de las distancias medidas. En  se observa lo que podría ser una primera conjetura

se observa lo que podría ser una primera conjetura